Hypothesis: Repeated experiencing of the materials will aid comprehension.

It’s the crescendos that drive me to distraction. They’re ubiquitous. It’s like someone ending every one of their sentences with, “. . . !” And yet, curiously, an impetus is still renewed from moment to moment throughout the twenty-five-minute duration of Edgard Varèse’s Amériques. The piece has a hallucinatory, fever-dreamish aspect that’s both exhausting and compelling. Listen to it enough times and you start to really get a sense of the relative weight of each of the sound aggregates.

But, Varèse makes it difficult to hear these gestures as simply sounds unto themselves. My memory keeps leaping to the fore, keeps trying to “help” my listening. The opening moment of Amériques (a lone alto flute intoning a portentous phrase) re-minds me of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps (actually, a lot of Amériques remind me of Stravinsky’s earlier work). And then the spook-house strings at the two-minute mark unavoidably call up memories of Roger Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death. I really do want to hear this piece on its own terms, but how can I when my associative mind will not (cannot?) settle down? How do I avoid the cornball alleyway of my memories?

I listened to the piece both in single sittings and serially, bro-ken up into three (or more) sections, listening on successive occasions. And still I lose track of where I am. The piece rarely repeats itself, so I can’t accuse it of compositional bloat. But it is a sprawling piece. There’s a lack of predictability in all of its registers that rather than being enlivening is, well, a little boring. If every lived moment is a singularly unique moment, then why value any one of them? Why choose a single moment when any other will do? If every moment of an art experience has the same affective weight, then does the accumulative effect of these moments carry any meaning? Listening in a constant state of shock and surprise stops be-ing shocking or surprising by minute five or so. And in that case, why, as a composer or a listener, keep going?

I can tell that Varèse heard something in Stravinsky, Debussy, and Berlioz that almost everyone else missed. But I can’t put my finger on what it is. Almost all musicians picked up on the timbral and harmonic implications of those composers, but Varèse seemed to have sensed formal implications that I’m not sure most of us have caught up to even now. So, here’s a piece of art that clearly has been put together with a lot of care, a lot of craft, but it’s informed by a sensibility that I don’t have much in common with. Is there anything of value I can say about my experience of Amériques?

Hypothesis: Reading the artist’s aesthetic idea(l)s will enhance the experience of the art.

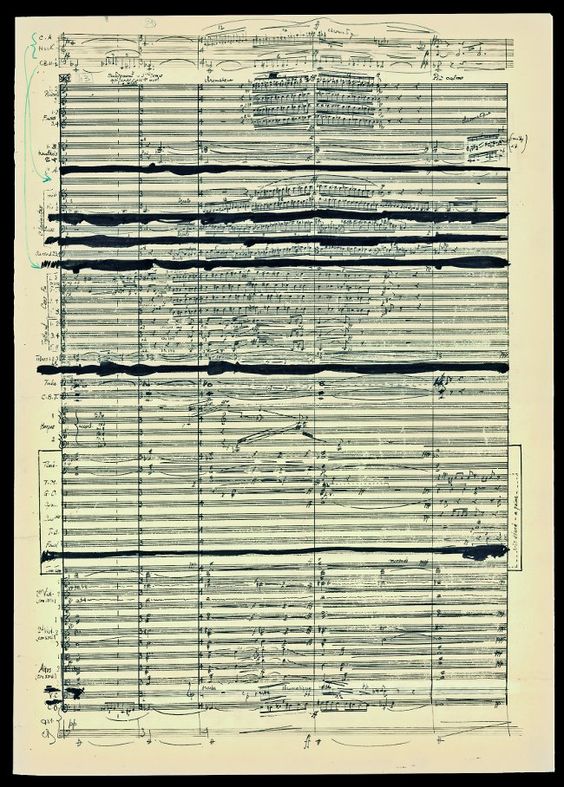

There’s a literal sensuousness to the sounds of Amériques. It’s clear that Varèse was one of the first European sound-artists who really utilized the physically verifiable components of sound: attack, duration, decay, pitch, and amplitude. And that’s reassuring as all the literature about him over-emphasizes his interest in this. He’s credited with coining the term “organized sound,” comparing his compositions to the phenomenon of crystallization and was fond of Wroński's definition of music as “the corporealization of the intelligence that is in sound.” Hearing Varèse “walk the walk” encourages me in thinking that all the “talk” about the art wasn’t just blather. And the emotional affect this sensuousness imparts is both surprising and inviting. Far from making his music alienating or “difficult,” Varèse’s attention to the fundamentals of musical apprehension make his work genuinely compelling.

But do his words clarify the experience of his music? When he and others describe “sound masses” “intersecting,” “colliding,” and “penetrating,” is that helping us to listen (in the Oliverosian sense of the term) to his music? Or is that imposing a cage-like framework that makes us perform a dreary kind of scavenger hunt when hearing Amériques?

Varèse clearly wanted people to recalibrate their relationship to music and sound. And part of the reason he wanted to do this was because of his ideas about historical necessity. (It helps to remember that he was a fan of Busoni’s Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music.) But this particular recalibration requires a certain kind of “forgetting.” When the siren first enters at 2:38 or the wah-wah trombone at 15:01, what do I do when all I can think is “air raid” and “cartoon” at those moments ? How do I forget the history my unconscious has created? And what do I do about the music his fans and students wrote. (For those of you who are original-series Star Trek fans, I think you’d be hard-pressed to avoid conjuring images of Captain Kirk battling it out at the 18:18 mark.)?

What if all these gestures sound like symphonic episodes rather than organized sound? Did I fail if I can’t hear collisions and transmutations ? Or did Varèse fail in his “fight for the liberation of sound ?”

Hypothesis: Experiencing additional art objects from the same creator will create an informative context.

The funny thing is that while I have an ambivalent relationship to Amériques, I really love the pieces that immediately followed in its wake. Hyperprism, Octandre, and Intégrales are really amazing, fun, and engaging. And while I don’t love Arcana, I found it more captivating than Amériques. Did reengaging with these pieces increase my enjoyment of Amériques? Not appreciably. Did they help me understand it any better? I’m honestly not sure. Does this difference in enjoyment speak more to my issues with large-scale symphonic music than anything else? Quite possibly.

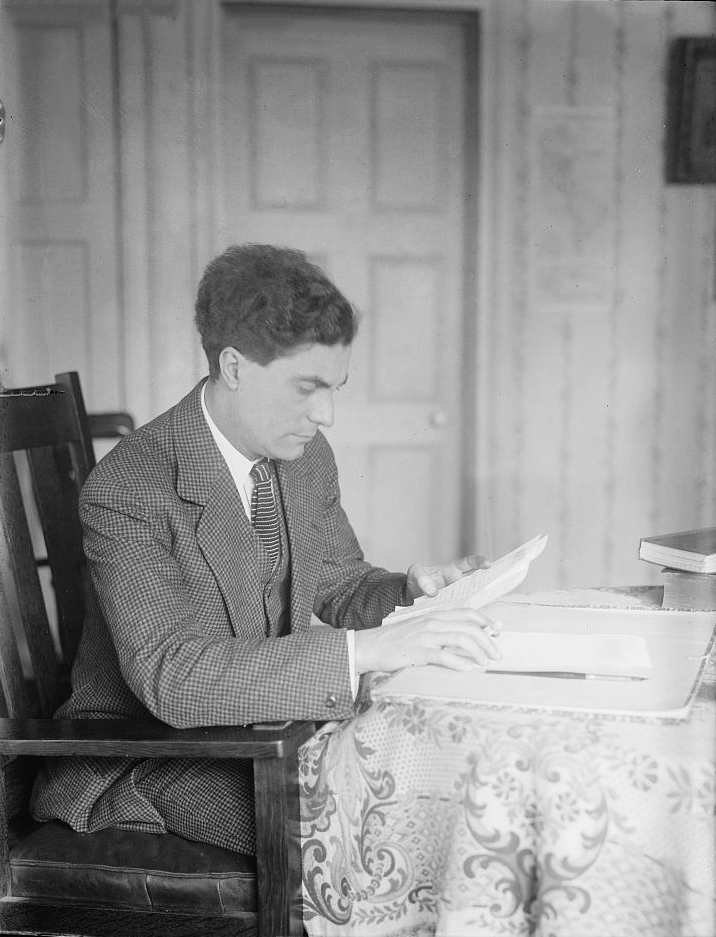

Interestingly, Amériques wasn’t the piece that established Varèse’s reputation as a composer. He arrived in New York City in 1915 and made his big splash in 1918 conducting Berlioz’s Requiem. He followed this up with a series of well-publicized conducting engagements. They were well-publicized because Varèse had presented himself as a dashing, continental modernist who was emphatically not German (the U.S. entered WWI in 1917 by declaring war on Germany). Varèse purposefully programmed new compositions by living composers of the time (composers primarily not from Germany). In many ways, he was the prototype of what Leonard Bernstein and Pierre Boulez would become for the New York City classical music scene following the World Wars : a handsome, uncompromising modernist bent on introducing new music to the general public.

In 1921, when Varèse completed Amériques, he established the International Composers’ Guild with harpist and composer Carlos Salzedo. In the public’s imagination, this was all an extension of his work as a conductor and promoter of living composers. The first time one of his compositions was premiered wasn’t until April of 1922 and that work was Offrandes. A piece for orchestra and soprano. It’s a fascinating and unique work, but it was only performed once for the niche audience the ICG was just starting to build in its inaugural season. The next premiere was Hyperprism in March of 1923. It’s a barely four-minute piece for brass, woodwinds, and percussion that he completed two years after Ameriqués. The premiere of the piece was for the ICG patrons and received poor notices, but in November and December of ’23, Leopold Stokowski conducted it with the Philadelphia Orchestra in both Philadelphia and New York City. The piece made a huge splash amongst critics, particularly Lawrence Gilman of the Herald-Tribune. This piece, like Amériques, also had moments for an emergency siren, but this was the first time an audience would hear that. The general public didn’t hear Amériques until 1926, and by then Octandre and Intégrales had also been performed. So, all the pieces heard by critics and concert-goers before Amériques were: (a) shorter, (b) for much smaller ensembles and (c) focused on many of the elements that made Varèse notorious in the public imagination.

I’m not sure I like Amériques any more than I did before knowing this history, but I’m much more appreciative of its existence. But how important was this piece for his audience in the 1920s? It was premiered fifth, three years after his biggest publicized debut as a composer and eight years after his presence was made public. It’s a storied piece both for its scale (it calls for 125 to 140 musicians) and its initial place in his very small oeuvre, but it’s rarely played and hardly listened to. Is it an overlooked masterpiece? A Rosetta stone for his musical world? An overly long piece that was important simply so Varèse could get it out of his system? A refutation of his reputation as a stark revolutionary who had cut off all ties to Western European art music? I think it’s all of these things. Because, in the Rashomonesque history of human culture, its historical significance depends on a variety of factors. At the individual level it depends on when one learns specific pieces of history (my perception of Amériques was altered upon learning the details of its premiere). At the societal level, Amériques’s significance depends on a series of factors that only seem to reveal themselves years after the described events have passed. While I might not check in with Amériques regularly, I’ll always hear echoes of it in the music of Bernard Herrmann and Alexander Courage. From this perspective, history becomes an amorphous, fluid body of knowledge where things are added, subtracted, diminished, and amplified. And like a liquid, the density of history as well as our relative position to its deepest pockets affects our perception of an art work.

Hypothesis: Learning about the artist will elucidate the art object.

Varése the artist wanted people to hear his music as its own self-generating universe. A place where each sound’s function could only be determined within the parameters of the composition it-self. Varése the person wanted to be acknowledged for his hard work, his craft, and to be offered the assistance he knew an artist of his stature should be accorded. These are irreconcilable desires. By creating pieces (of which Amériques was the first) that constructed themselves out of their own constituent sounds, not out of their relationship to other artist’s works, nor from their possible significance to the culture at large, Varèse created autonomous works that could not participate in the world as the rest of humanity understands it. And when you create that kind of work, incomprehension is sure to result. And incomprehension understand-ably leads to dismissal.

There’s a natural tension produced by these irreconcilable and competing desires, and that tension creates a space. A space between the animating force and energy of his pieces and my experience of these same pieces. And to relieve the tension, I invariably try to fill up this space. Sometimes I use biographical data as the filler, but just as often it’s historical context or technical information in the form of theoretical descriptions. And once this tension-laden space is filled up with other ideas, with words, then I tell myself I’ve understood. That I’ve reached some level of apprehension. But I haven’t, not really. I’ve simply smoothed over a lightning-filled space where on one end is the energy Varèse gave over to make his object and on the other end are my open and uncomprehending ears.

In researching this essay, I benefitted greatly from reading Carol Oja’s descriptions of Varése’s critical notices from the 1920s in her book Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s published by Oxford University Press in 2003.

I also learned an immeasurable amount listening to Claire Chase’s three-hour long interview with Varése’s amanuensis, the great composer Chou Wen-chung. That interview can be heard in its entirety on WQXR’s website.

There are multiple recordings of Amériques and I really did try to listen to all of them. But, in the end, the one I kept returning to was Pierre Boulez’s second recording of the piece done in 1995 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This recording has been recently re-released by Deutsche Grammophon and was the source of all the track markers I cited in my essay.