In 1967 percussionist Michael Ranta left the United States and never looked back. In the ensuing fifty years, he amassed a vast and singular body of work, while collaborating as a performer with some of the most significant composers of the twentieth century including Harry Partch, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Jean-Claude Éloy, Helmut Lachenmann, Tōru Takemitsu, Luc Ferrari, among many others. In 1979 after over a decade of travels across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, he settled in Köln and opened Asian Sound, purveyors of unusual and hard-to-find non-Western percussion instruments, which still operates today.

Ranta’s music is multifaceted and presents an alternative to the volume, virtuosity, and rhythmic regularity of most percussion music. Rather, it employs patience, mindfulness, grace, and, above all, a profound affection for the instruments, their sounds, and the worlds from which they came. His enormous oeuvre resists easy summary, with work as a new music percussionist, electroacoustic musician, composer of chamber music, improviser, and visual artist. In March 2022 percussionist and composer Sarah Hennies and Swiss composer and writer Vincent de Roguin spoke to Michael Ranta in hopes of shedding light on his fascinating life in music.

•Sarah Hennies and Vincent de Roguin

{Editor's note: This is the full interview which appears in an excerpted version of the print edition.)

SHHello Michael! What are you up to these days?

MRWell, I am in the process of getting rid of all the open reel tapes. I listen to a tape and think, "That's a wonderful sound; I can't throw that away,” so I am in the process of digitizing them. I have three machines—a Revox and two others—in case one breaks down. Technically I can't do it myself, so I have hired someone to digitize the tapes for me. We need another five or six sessions. I have the next one on Saturday, it'll last about five hours. The tapes have gathered a lot of black material on them, and when you play it that material ends up on the heads. So, after every run-through the heads must be cleaned.

VdRIt's important that this process is done properly right from the start. Once it's done, you can't always go back to the tapes, because sometimes they simply disintegrate. Or if the transfer isn't done correctly, as it happened a lot in the early 1980s in many TV corporations when they transferred the film reels onto these then-new video formats and threw the reels away. Now we're left with these sub-standard versions of once beautiful documents.

MRExactly. [Karlheinz] Stockhausen warned me about that in the 1990s. He told me that the original tape of Kontakte, one of his famous electronic pieces from the late 1950s, had lost its treble tones. He was so frightened that he sent it to a special company in Hamburg and asked if they could save the high frequencies on his old tape and convert it to digital. They did and it was successful. Stockhausen said, "I'm warning you Mike. Do this with your tapes, too." [laughs] That warning came in the 1990s, but I was too busy with other projects, and my tapes just stacked up on a shelf until now. But I don't burst into tears if I listen to one and it's not worth saving anymore. That's just fate.

SHThe earliest thing that we really know about you musically is being at the University of Illinois. Is there anything prior to becoming, for lack of a better word, "a classical percussionist," that you would like to tell us or that you think is interesting? You were born in Duluth, Minnesota.

MRWell, how did I get close to drums? My father was a freemason, and they met once a week and had a drum and bugle corps whenever there was a parade—for the Fourth of July or for the Victory over Japan. And my father brought the drum home after the practice, so it sat around. When I was in fifth or sixth grade, maybe already junior high school, I would start to play on the drum and I got interested. With climate change it's not like this anymore, but back then, the winter in Minnesota started on the third week of October, and the snow finally melted at the end of April. The snow was up to the waist throughout the winter. So, there was a lot of time to just sit home, and I found that NBC often put the New York Philharmonic on television with Leonard Bernstein conducting. We're talking about the 1950s here. I was fascinated. It grabbed me. I was not impressed when the Beatles came out. OK, I could listen to them, but I was on to something different. In junior high they called me "long hair" because I was interested in classical music. [laughs] Now, Duluth, Minnesota was a city of a 110,000 people just across water from Superior, Wisconsin, and together they had the Duluth Superior Symphony Orchestra. But it was all amateurs, of course, mostly music teachers from the area with a German immigrant as conductor, Hermann Herz. They only had about four concerts a year. With the Duluth Junior Symphony, there was only one concert a year with one rehearsal per week, so I joined that. I did the best I could. The percussion teacher in Duluth wasn't bad, but I knew I would have to get out of Duluth if I was to follow my dreams. The big turning point was in 1960. After high school graduation, I went to Interlochen Summer Music Camp and that changed everything. The teacher there was Jack McKenziei, who taught at the University of Illinois. I was very happy studying with him; I learned the marching grip on the snare drum or how to hold the mallets for marimba for example. Sometime in the second or third week of August, just before the Interlochen days were over, Jack said, "By the way Mike, where are you going for University?" and I said, "Oh, I don't know." "What? You don't know? But school starts in three or four weeks!" [laughs] I asked, "What about coming to you, to the University of Illinois?" He said, "Well, we have twenty-one or twenty-two percussion majors, most of whom were in music education and only one or two in bachelor music/arts..."

SHI'm laughing because that's exactly how it was when I was at the University of Illinois in the late 1990s. Forty music education majors and three performers or something...

MROh, you went to the University of Illinois?

SHYes.

MRI'm still in touch with Tom Siweii.

SHWhen I saw that you went to school with him, my jaw hit the floor because he was my first percussion teacher. He retired after my first year.

MRI studied percussion with Jack McKenzie, and Tom Siwe was a student in graduate school. I was a freshman. I got to University of Illinois in 1961.

SHDid you study with [composer, electronicist, cybernetician] Herbert Brün? He passed away in my last year at Illinois, and his class really changed my life.

MRI studied composition with him, but a bit later, around 1965. I studied computer music with both [composer and chemist] Lejaren Hiller and Brün, actually. They were quite similar in their approach, both centered on composing with the aid of a computer, which took the entire space of a large room. I did a composition with the computer called Algol Rhythms as my main piece for my master’s degree recital in 1967. That was the whole year's project, and I still have the score. It was created using printouts of material generated by algorithms. I asked the computer to give me random numbers between one and seven that were each assigned to a different instrument: bass drum, snare drum, two tom-toms, two suspended cymbals, and a hi-hat. For generating the numbers, I also specified different percentages for each number, for instance a fifty-percent chance that it would be a four. This process was repeated hundreds of times and then the order of the instruments had to be decided. I then used a similar procedure to determine rhythmic values: quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, etc. That is how my piece was constructed. Those were the very early stages of computer music. But I was never good at mathematics and never returned to using the computer as an aid to composing.

VdRYou have also composed many tape works throughout your life; did this interest start at the University of Illinois already?

MRYeah. A student friend had the key to the electronic music studio, so we went there and played around with the tape recorders, making sounds, using sine tones, altering them. I learned a little bit there but was not greatly interested. I was more attracted to performance then. My interest in composing musique concrète came later, in the early 1970s.

VdRDid you pursue other studies around that time?

MRYes, and even then, I wanted the best. The story I'm going to tell, it almost makes me start crying. I took the Greyhound bus to New York City in 1961, I think. At the time, for eighty or eighty-five cents you could get to the fifth or sixth floor of the Metropolitan Opera, standing. It was the old Metropolitan Opera on 39th Street, before they moved it to Lincoln Center. So, I went to a Wagner opera, Siegfried, or something. I could see the timpanist, and I said, "That's what I need! That's exactly what I need!" So, I went down to the exit and I waited outside the door until the timpanist came out. His name was Richard Horowitz. I told him, "I'd like to study timpani with you." [with heavy New York accent] “What? Kid, I haven’t got time...” I probably looked like I was about to start crying so he said, "OK, come tomorrow at ten o'clock." I was staying at the YMCA that night. The next morning at ten, I went there with my timpani mallets. We took an old elevator up to the fifth floor, and I showed him my tremolo on timpani. He just shook his head and said, "No." [laughs]

So, we started timpani lessons and that was really fantastic. But how could I practice? There were two tricks. The first one worked for a couple of weeks: I would go to Juilliard School in the music department, and there was no guard at the door. I would just go in and find the room with the timpani, and if nobody was there, I would practice until somebody came and said, "What? You're not even a student! Get out of here!" [laughs] Then somebody told me about Carroll Sound. It was a recording studio in New York, and they would have a band in there starting at maybe ten in the morning. And at one o'clock, they’d have a two-hour break for lunch, which is when I would be waiting. I would pay Carroll Sounds seventy-five cents an hour or something so I could go in and practice on the timpani during their lunch break. That changed everything in my abilities. I went back to Illinois, but I repeated that a couple of times over the years, going New York City to study with Richard Horowitz.

VdRIs it around that time that you visited Edgard Varèse?

MRYes. Interesting how this happened. In the summer of 1961, I was in the student orchestra of the Pierre Monteux School for Conductors and Orchestra Musicians in Hancock, Maine. I got to know one of the conducting students there, Carlos Rausch from Argentina, who knew Mauricio Kagel well when they were both younger. Sometime later, I met him again in New York City and told him how impressed I was with Ionisation and Déserts, both of which I had performed in ensembles at University of Illinois. Carlos said, "Call Varèse. Here's his phone number." I was only a twenty-year-old kid, but Carlos was insistent. I called Varèse and he invited me for morning coffee at his apartment in Greenwich Village. When I told him I had performed two of his pieces, he got very excited and shouted, "My publisher never informed me about this! Where was it?" "University of Illinois," I answered. "Where is that?" "150 miles south of Chicago," I answered. He didn't seem to understand and asked the question twice. He then repeated many times that New York City was the only place for music in the USA—nowhere else—and that, as a musician, one had to live in New York City. We went on to have some small talk about various things before he showed me one of his gongs, saying, "I found it on the street in Paris, a dog was urinating on it." Then I showed him a gong and tam-tam mallet I had made and brought with me. In the early 1960s, it was rare to find gongs from Thailand and tam-tams from China. Therefore, good mallets for these had not yet been developed in the West. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the import of gongs and tam-tams started and grew rapidly, and the makers of mallets developed their products accordingly, such as Paul Chalklin in the UK and some others in the USA. Anyway, Varèse tried the mallet on his gongs and tam-tams and liked it very much. Perhaps I even gave it to him, as I don't see it in my collection anymore. After about two hours, Varèse told me, "Get in touch with me after you move to NYC, the only place for music in this country." I believe he passed away one or two years later.

VdRWhat were your first professional experiences as a percussionist?

MRI had lung collapse in 1962 and 1963, and I had to drop out of the fall semester at University of Illinois. I came back in 1965 to finish my studies. In the meantime, a friend told me about the small North Carolina Symphony orchestra and that I should ask if they had a place for me and they did! The orchestra started around the fifteenth of January and played to around the tenth of April in all the small cities in North Carolina. It was just a chamber orchestra, twenty-one players including harp, one percussionist, and timpanist. That's when my experience as a player started. Between my time in New York and the North Carolina Symphony, I was able to have a six-week season with a full-size orchestra.

During this time I had a meeting with John Crosby, the conductor and owner of the Santa Fe opera, and he said, “Oh, you were in the Pierre Monteux School for Conductors and Orchestra Musicians in Hancock, Maine?” Actually, I wasn’t a student there, but they needed an orchestra there, the “guinea pig” orchestra, so to speak. So, I got a room and three meals a day for playing in that orchestra in Hancock. It was great, and I gathered a lot of experience there playing timpani. Anyway, after John Crosby heard that I played in the Pierre Monteux orchestra, he just said, without any audition, "The second percussion is open in the Santa Fe Opera for the summer season. Do you want it?" I said, "Yes!" I stayed with the Santa Fe Opera for five summers, which was very nice. I was twenty or twenty-one years old and playing a lot of modern opera: Shostakovich's Die Nase, Hindemith, and many others. Also, every summer the Santa Fe Opera did a Hans-Werner Henze opera. [laughs] Playing outdoors looking up at the night sky was nice, and the dry climate of New Mexico was good for my health. Around the same time, Werner Torkanowskyiii announced that there’d be auditions for the New Orleans Philharmonic, a job that was to begin in the fall. So, I took the audition and asked the orchestra manager, "Can you tell me how many came to take this audition?" He told me six. "What do you think my chances are?" He said, "Good." A bit later I got a letter from them that I had gotten the job. But after one season at the New Orleans Philharmonic, the conductor came to me and said, “I heard you didn't sign a contract for next year!" I said, "No, I'm going to Petaluma, California, to work with Harry Partch."

VdRHow did you meet Partch?

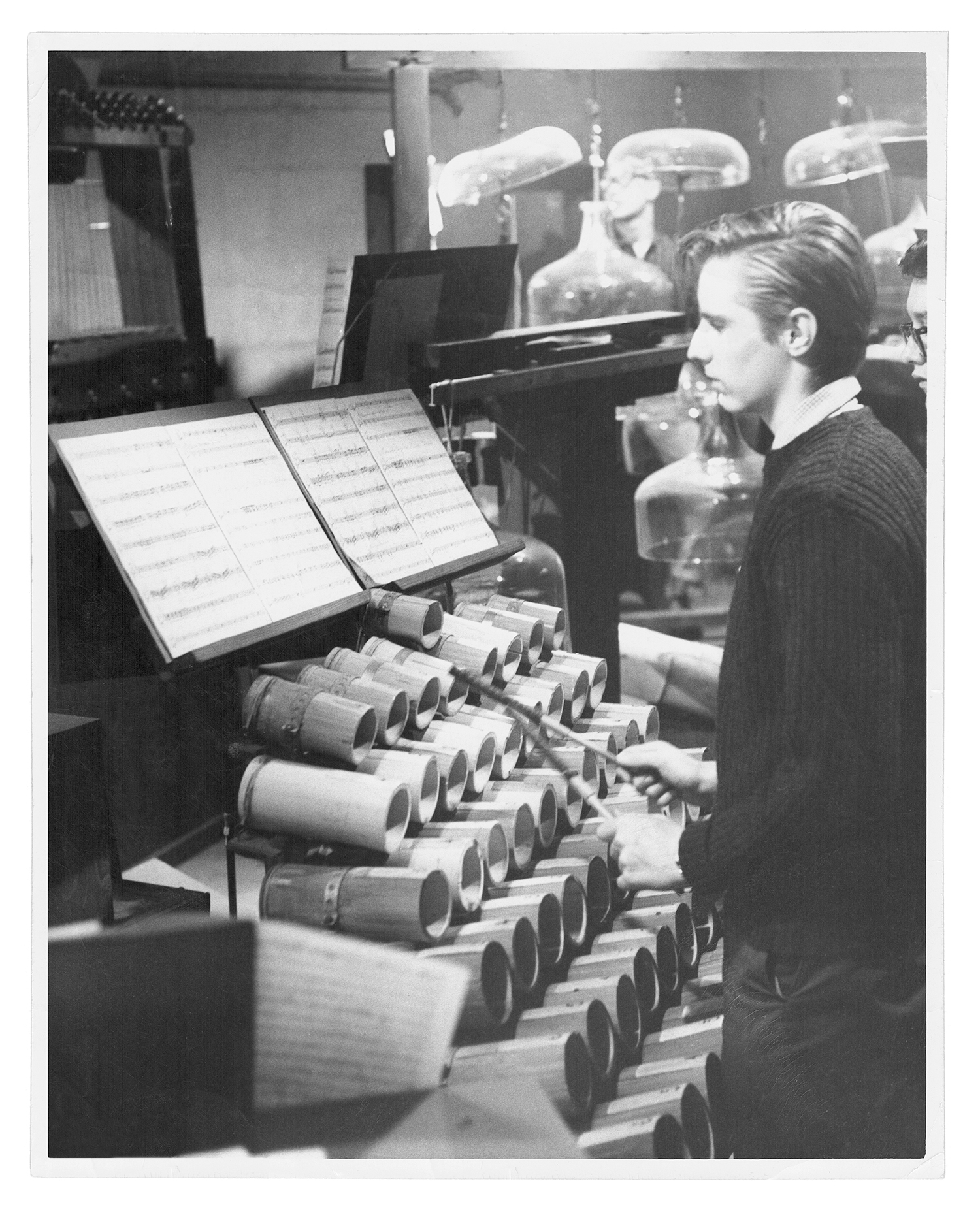

MRI started working with him in the fall of 1960. When I got to the University of Illinois as freshman in September 1960, there was an introductory meeting. Jack McKenzie gave us the schedule and said, "Look at the door on the percussion room. There'll always be a notice which players have to show up for the percussion ensemble, which will meet every day at eleven o'clock." Then he talked about other details, and we all got a key to the percussion room and the storage for percussion instruments. Then Jack McKenzie said, "By the way, mark your calendars; every Thursday night at seven o'clock is reserved for Partch rehearsals!" I leaned over and whispered to my neighbor, "Partch? What is that? Something to eat?" [laughs] McKenzie said, "Harry Partch; you'll see what it’s about on Thursday night. Here's the address, be there!" Partch had been there since 1957, I think. He was living in Champaign, so I rode my bicycle there. All the other percussionists were there too. Partch said, "Look around, whatever instrument is attractive to you, that's the one you'll be playing." I picked the Boo [Bamboo Marimba]. We were quite busy in the fall of 1960, because the premiere of Revelation in the Courthouse Park, was in January or February 1961. Later that year I played in Rotate the Body in All Its Planes and Bless This Home. At the end of the year, we started rehearsals for his next piece, Water, Water, in which I had a big solo part performing on the surrogate kithara, a small string instrument on wheels, which the performer can move around the stage while playing.

VdRAlthough Partch eventually left the University of Illinois, you continued working with him for many years after that.

MRYes. In 1962, his grant from whatever foundation ran out at University of Illinois. It was not renewed, although I think it was already quite generous that he got grants four years in a row. So, Harry packed everything and moved to a chicken hatchery in Petaluma, California. I didn't see him until I departed from the New Orleans Philharmonic at the end of the spring season, around the tenth of April 1964. I drove all the way up to Petaluma with a stop in Oklahoma where my old University of Illinois comrade Danlee Mitchelliv was in an orchestra. In Petaluma, Partch and I mostly practiced for his piece And on the Seventh Day Petals Fell in Petaluma. Mitchell and I recorded it, but the recording had some problems.

In the summer of 1964, Partch moved out to San Diego. After another summer season with the Santa Fe Opera, I worked with him at San Diego State University. I wanted to keep getting credits so I could at least finish a bachelor, so I also started studying again. Harry was promised a grant from the University of California San Diego, but it didn't happen. There we mostly worked with Partch and Mitchell, who took on all Partch's productions after he passed away. After San Diego, there was Venice, California, where I stayed with Partch for a while. We also played a concert up the mountains in the north of Los Angeles around that time, and then I thought, "That's it Mike. Go back to Illinois and finish your bachelor’s degree!" So, I went back, finished my degree, and moved to Europe in 1967.

VdRI've read somewhere that you played with Partch until 1968.

MRThat's because some months after moving to Europe, Mitchell wrote me saying, "There's going to be a concert, and after the concert, there'll be a recording of many Partch pieces for an LP release. Do you want to participate? You'll have to stay for six weeks in Venice, California for rehearsals with the ensemble. You can sleep in Partch's apartment there. Then we'll all fly to New York City to the Whitney Museum for a live performance." The concert was completely full; Lou Harrison was there, and I believe Aaron Copland, too. When the concert was finished at around eleven o'clock, they made some very strong coffee, and we recorded that LPv from eleven thirty to about six in the morning. That was my last meeting with Partch; a day or two later I was flying back to Europe.

VdRWas your working relation with Partch project-specific—only for certain pieces—or were you a permanent collaborator during the decade?

MRI think I played on mostly everything that Harry did in the 1960s. I left in 1967, and after that 1968 recording for CBS I was involved with, the Partch ensemble continued in California. Partch lived at least another five years after that, I think.

VdRHow has these years alongside Partch affected you as a musician? What sort of relationship did you have with him, besides playing together?

MRWell, with Partch your ears changed a lot because of his microtonal scales. But I was never very good in music theory. I got a bit better when doing my bachelors, because you had to do counterpoint and fugue, but I was never good with things like physics, mathematics, chemistry. I learned to repair Partch's instruments, but only when he showed me how! [laughs] I was his assistant; he showed me what he needed and then I helped. There wasn’t anything really creative from my side, it was really about helping him—repairing the instruments, packing them, and then, of course, rehearsing and recording.

What else can I say about Parch? He was a drinker, and he sure liked his bottle of whiskey. [laughs] Also, it was through Partch that I met Emil Richardsvi, who was in the ensemble. I drove up every three weeks from San Diego to his studio in Hollywood for mallet lessons, and my marimba and vibraphone playing improved so much after studying with him! He put quarters on my wrists, and I had to play the marimba rapidly and not let the quarters fall down. Once, on my way to a lesson with Emil, my tire blew up. By the time I had changed it and got to his studio, he was already gone. He had left for a recording session with Frank Sinatra! On the rare occasions that a vibraphone was needed in a Sinatra song, Emil Richards was the one to play it, and I was supposed to go with him. Sinatra was very generous with guests in his live recording sessions—he could have up to a hundred people there—but I missed my chance that day! [laughs]

VdRWhat other sort of influence did this intense relation with Partch have on your practice?

MRIf I had to find one word, it might be carpentry—building instruments to create the sounds I had in mind. I had no tools or workshop as a student from 1960 to 1967, but from 1967 to 1972, I started to make the instruments needed for performances of pieces by Lou Harrison and John Cage. In the latter part of my seven-year stay in Taiwan in the late 1970s, I composed some pieces for my students in junior and senior high school for which I constructed some wood and metal instruments. After returning to Europe in 1980, I made some more instruments, like a simple bass marimba without resonators, for performances of pieces by [Helmut] Lachenmann, [Jean-Claude] Éloy, and others. But it was all rather simply constructed, not highly refined like Partch's.

SHIn 1967, you moved to Germany and immediately started working with Lachenmann and Kagel, among others. Did you have experience being a percussionist in new music chamber groups before moving there?

MROh yes, the contemporary chamber players at the University of Illinois. That changed my whole life, too. There were ten or eleven players, and, in August 1966, we went on a five-concert tour in Europe. Starting at the Darmstadt festival, we played pieces by my teachers at University of Illinois, Salvatore Martirano, Hiller, Brün, and a few others. We were a bit booed out by the Darmstadt audience, as they were primarily Stockhausen lovers. Stockhausen himself got up and left the concert in the middle of the Martirano piece, and all his students got up and left with him. [laughs] Hiller arranged the tour, and he had good connections in Europe. After Darmstadt, we came to Cologne, and, after a three-week pause, we got to Warsaw for the Autumn Festival. Then we went to the American Center in Paris and on to London, at Wigmore Hall, after which we flew back to the United States. So, after that experience in Europe, I thought, "Ha, this is for me, I'm going to move here." [laughs]

VdRYou also made some important connections on that tour.

MRWhen we played in Darmstadt, a guy came up to me—very shy, with glasses—and he gave me a score. He didn't go to the two other percussionists in my group; he only came to me. He said, "This is for solo percussion. I just finished it." On the score it was written, "Dedicated to Siegfried Fink." The score was Intérieur 1 by Helmut Lachenmann. Fink [a German percussionist and composer] never performed it. I replied, "Thank you very much,” and just put the score in my luggage. Then, one year later in Santa Fe, the house I was staying in had a room big enough for a four-octave marimba, a vibraphone, a set of tom-toms, and a set of tam-tams, all borrowed from the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. I was then able to make the setup for Intérieur 1 and play it. I wrote back to Helmut to tell him, and when I arrived in Europe in the fall of 1967, I was ready for the performances he had organized. There were four pieces on the program, Intérieur 1 for solo percussion; a piece for solo percussion and large orchestra, which the Sinfonie-Orchester des Hessischen Rundfunks premiered with Lukas Foss conducting; Trio Fluido for marimba, viola, and clarinet; and a piece for chorus and four percussionists, which was premiered in Bremen. I was involved in all the productions of those four pieces.

VdRFrom this early collaboration with Lachenmann, your professional life rapidly flourished in Europe.

MRYes, aside from Lachenmann, there was work with Nicolaus A. Huber and Martin Guembel in Stuttgart. I was also around Europe with [German electronic music pioneer] Josef Anton Riedl in those years. He was quite eccentric; his music was mostly improvised, and I don’t think he wrote more than one or two scores in his life.

To be a professional player in Europe, I had to own my own instruments. I mentioned earlier that all percussion majors at University of Illinois had a key to the percussion storage and the percussion practice room. Somebody could then call me up and say, "Hey Mike, can you come over and play the rompompompompompom-pom on timpani at this concert of Bach's Weihnachtsoratorium? It pays ten dollars and fifty cents." I would say, "Yes, of course." Since I had the key to the percussion storage it was no problem to take out the two timpani, put them in my old Buick, put on the shirt and tie, play the concert, and bring the timpani back. When I came to Europe, no student percussionist at the conservatory in Munich had the key to the storage room! [laughs] And it was absolutely forbidden to remove any instruments from the room! When we had to practice Trio Fluido, the Bavarian Radio said, "Well, Mr. Lachenmann, we'll make a compromise. We'll bring the marimba to a small room, and you can have a rehearsal there, but the marimba cannot leave the building!" So, once I was in Europe, there was no way around this. I had to own my own marimba, vibraphone, glockenspiel. That's why my first years in Europe were really poor for me; all the money I was being paid for concerts had to go to buying these instruments.

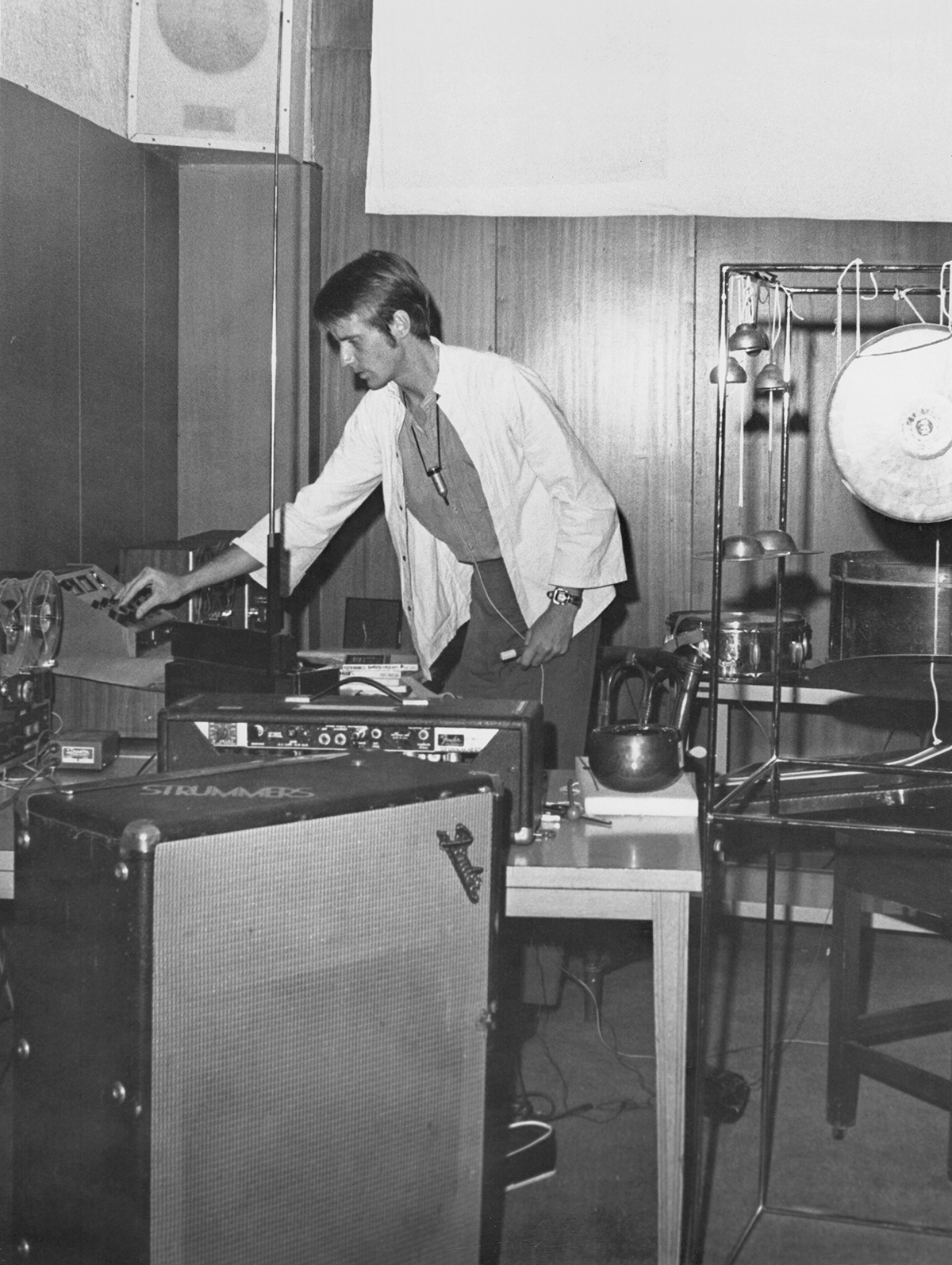

VdRHow did the recordings you made with [German record producer] Conny Plank come about? These are the so-called Wired sessionsvii from April 1970, with Plank, Mike Lewis, and Karl-Heinz Böttner and the Mu sessionsviii with only Lewis and Plank, which were recorded in late December 1970.

MRLet's see, how did that go? I met Plank in a sponsored concert for the West German Radio, I think in Bonn. I was involved in the production of a Kagel piece with two guitarists, Böttner and Wilhelm Bruck, and Plank was the tonmeister [German term for recording engineer/producer]. He was still in Hamburg, and he had not yet opened his studio near Cologne. One day I went up to Hamburg to record something with him, Böttner, and Lewis. Lewis wasn't part of this academic scene. Of course, we would all loosen up with marijuana and hash and say, "Let's have a session." We became friends and decided to carry onwards and work on other things together, that's all. In the early 1980s, when Plank had moved outside of Cologne, I would go out and work there together with him. At his studio, I also recorded sessions that ended on my LP, MU V / MU VIix.

SHSoon after the last session with Plank and Lewis, you started working with Stockhausen. How did you meet him?

MRI did a very clever thing, and I had no idea at the time how clever. [laughs] I had my bachelor’s recital at the University of Illinois in 1966—January, I think. For all bachelor’s and master's recitals, there was always someone up in the sound studio, and all concerts were recorded. A couple of days later, the engineer would see you walking down the hall and tell you to come pick up the tape. So, for my bachelor’s recital, I played Stockhausen's Zyklus. At the time I thought I was the first to do it in the United States, but Max Neuhaus was actually the first. Anyway, I sent this open-reel tape to Stockhausen, and he was apparently impressed by my recording enough to write back a letter to my address in Munich, where I was then living with Lachenmann. In the letter he criticized many things in my interpretation, but at the same time, he said that many other things were great. As you know, Zyklus is a graphic score, so it's quite open.

Years later, I was living in a hippie commune in Peterskirchen, Bavaria, with the artists Paul and Limpe Fuchs and all kind of strange people. [laughs] [German model and actress] Vera Gräfin von Lehndorff had a big house, and she liked having artists staying there. The rent was very reasonable, but there was only one telephone down on the ground floor. One day someone shouted, [really stoned voice] "Miiiike, telephone for you. Karlheinz Stockhausen is on the line." [laughs] Stockhausen told me, "Hello Michael, I'd like to invite you to Expo '70 to play Zyklus, Kontakte, and Aus den sieben Tagen." Stockhausen had this invitation from the West German government to represent Germany at the universal exposition in Osaka, Japan. So, I played Zyklus twice a day for six months. Every second day was free, so I played it maybe 130 times! I remember there were two pianists, Péter Eötvös and Gérard Frémy but I was the only percussionist. [laughs] It was a quick version of Zyklus, it had to be just under fifteen minutes. I also played Kontakte twice in the night, along with a very free version of Aus den sieben Tagen with our team. There were maybe twelve or fifteen players and six members of the vocal ensemble. The schedule started at three in the afternoon until six, when we had a short break for dinner, and at seven, the evening concert started. At the end of the evening, a bus brought us back to Kyoto to our hotel at around ten. It was very well organized. Kagel was very sour and angry, of course, that Stockhausen dominated the whole West German pavilion. All that Kagel got was some playback of his music when the pavilion opened at nine in the morning. Before the live music began in the afternoon, there was always tape music going on, other German composers.

VdRDo you see Stockhausen's domination, as you call it, as the result of his strategic flair or the fact that he really was such a pioneer in the field?

MRI think it's more the fact that he was a pioneer, yes. And he had solid relationships with people in power.

VdRHow does it feel to play the same piece twice a day for six months?

MR[laughs] First of all, Zyklus is always different. It's a graphic score, and although you have to play through its twelve pages, you can start on any page and end on the page before that one. So, I played it differently every day. Kontakte however was a little bit difficult. At the time, I was in love with the French school of musique concrète. I still am. Near the end of Kontake, there are these "wave tones," [imitates swirling pitches going in all directions] which are just pitches twirling around on the tape machine. I couldn't stand it, but I had to play. I thought, "It's not my way, but I have to do it. It's OK, no problem." It got to be routine; it was my job to do it. And that job gave me an opportunity to be in Japan. The country attracted me very much. So, when I got back in Europe after the six months ended, I had a few concerts booked in the fall. But I was careful not to book anything after New Year 1970.

A few days after New Year, I got on a plane and returned to Japan. I had also met Tōru Takemitsu in Osaka, who had come to watch and hear what was going on at the West German pavilion. We got to know each other then, and he invited me to witness a concert at the Steel Pavilion at Expo '70, where he was in charge of the music programs. When I returned to Japan, I did a lot of work with him and made many recordings, even after I moved to Taiwan, from 1972 to 1979. I think Takemitsu liked my style of playing and my creativity. Like many composers back then, he wrote graphic scores full of dots and lines that could be interpreted in any way. A lot depends on the performer. I often played Takemitsu's music alongside Yasunori Yamaguchi and Stomu Yamash'ta, who was my twelfth-grade student at the Interlochen Arts Academy in the winter months of 1965–66.

SHIn January 1971, you settled in Japan for some time. There, you continued to work as an interpreter for Takemitsu and others, but also engaged in composing your own music at the electronic music studios at NHK while improvising with a range of other musicians.

MRAt Expo '70 in Osaka, I had met an American guy, Joseph Deisher. He came to the West German pavilion once and asked if people we'd be interested in learning T'ai chi ch'üan. A few people said yes. So, we took lessons from Joseph during breaks between performances of Stockhausen’s music and that interested me a lot. Deisher lived in Tokyo, not Osaka, so I rented a small apartment in Tokyo, and every morning I went to a T'ai chi ch'üan class that was taught by a Chinese teacher, a former Chiang Kai-shek soldier. There were only two or three people in the class, but we learned, and it was good. Then one day this Chinese woman came to us, and she jabbered in Japanese, "I see what you're doing, but that is a Chinese art not a Japanese art. You're just doing a copy of it!" So, she invited me over to her house, and we got to know each other. She was a fairly wealthy woman, a traditional Chinese doctor. She said, "My family has a large house in Taipei; there are extra rooms upstairs. You can go there and learn T'ai chi ch'üan at the source!" So, I moved to Taipei in the fall of 1972. I was introduced to the class, and this time there weren't three people in the room but a hundred practicing in a large space next to a Buddhist temple near the center of Taipei! If you listen to my piece China Filch,x there's a recording in there of the teacher calling out movements.

This changed everything for me. In Japan, taxi drivers all had white gloves on, everything was so tchak-tchak-tchack. When I went to China and Taiwan, everybody was just easy going, and I enjoyed it very much, I felt good there. Waking up at 5:15 in the morning, taking T'ai chi ch'üan, sword dance, and Qigong lessons and going in the afternoon to university where I took Mandarin lessons for a year and half, partly sponsored by the government, which was interested in getting foreigners to Taiwan. At the peak, I think I reached 600 characters, which is about the level of a sixth-grader. Taiwan was also very affordable for me since I had a very low income. Over time, I started lecturing in music history and percussion at several music colleges and eventually became professor of music at the Hwa Kang Arts School. But like I mentioned, during my stay there from 1972 to 1979, I travelled many times back to Japan for concerts or recordings with composers like Takemitsu, Joji Yuasa, Saburō Moroi, Takehisa Kosugi, Toshi Ichiyanagi, and many others. With the money I could make from performances or recordings in Japan, I could live for a month or two in Taiwan. [laughs] I travelled to Korea as well, working with Kang Sukhi and doing modern music improvisation with other players. Towards the end of my time in Asia, I did a series of radio broadcasts for the WDR, programs on contemporary music in Thailand, Hong-Kong, Korea, the Philippines, and, of course, Taiwan—traveling to all these places and doing interviews and portraits of composers.

VdRDuring all those years living in Asia, you travelled quite a lot, for instance meeting [German polymath] Hartmut Geerken in Cairo in 1972 and starting a collaboration with him, under the name The Heliopolar Eggxi. I was wondering if all the audio material that is being issued on records in the last ten years came from Geerken's archive. Is it all from the same tour?

MRGeerken had everything. He had the time to do it, and he was in contact with people for the releases. Somebody in the Netherlands, I think, did an LP recently with an enormous price: 400 euros!xii [laughs] Geerken and I went on a sixteen-concert tour at the end of 1976, beginning in Tehran, ending in Osaka, and playing at most of the German cultural institutes between. We were traveling for about three weeks, and Geerken recorded those concerts partway. But I think that 400 euros LP was from a concert in Cairo in 1972, when I came back from my yearlong stay in Asia. I stopped in Cairo to see an Egyptian friend, Omar El-Hakim, who I knew from my days in Tokyo. He said, "I want to introduce you an interesting musician,” and he took me over to Geerken's house. We immediately became friends. The room was full of percussion instruments he had collected—all kinds of drums and gongs.

Geerken was a German teacher at the Goethe Institute, and he spent most of his life abroad. After Cairo he was transferred to Kabul, so I went there to stay with him at his house for almost six months. Then he was off to Lebanon, and then Athens until his retirement. He was a German teacher but always had a strong love for creating his own music and issuing the music of others.

SHWith Geerken, you're playing in places, I hope this is accurate to say, that kind of unusual music often doesn't reach, especially at that time. Do you have any stories of what that was like?

MRWell, our first concert was in Cairo in 1972. We got a good audience because of Geerken, but the Egyptians were kind of open to this new music anyway. As mentioned, in November and December 1976, we made our only tour together. In Tehran, it seemed nobody was really acquainted with modern music, but the Goethe Institute had a big name—it was the German cultural institute—so people would go to the concerts. They'd maybe say, "Oh, we've never heard music like this before," but nobody booed us out, at least not in Tehran! Then we played for three days in Delhi. The Indian audience was very quiet and meditative; they would just sit there. We had asked the Goethe Institute to supply local musicians to improvise with us as much as possible, but in Tehran and Delhi there were no guest players. In Calcutta, the Goethe Institute told us an Indian group would come and play together with us, but they ended up playing straight classical Indian music. [laughs] But it was OK! Then we played in Bangladesh, and that's where people got up and shouted at us: "That's no music! That's just junk sounds!" [laughs]

We went onward to Bangkok, meeting many people I’d already known there. Good and quiet audience; they liked the concert. The famous Bruce Gastonxiii came and played together with us. I had met him in Thailand previously. We played Manila after that, where people weren't so accustomed to modern music. We were a bit complicated for them, but it went OK. We had someone play the congas with us, not very interesting. [laughs] Then we travelled to Korea, where composers had been studying in the West, so the audience was very much acquainted with this kind of new music. Kang Sukhi and Hwang Byungki performed together with us, playing the Korean kayagumxiv. And, of course, the final concert was in Osaka. That was the most educated audience for this music. Ichiyanagi and Kosugi joined us that evening, and we also played my wife Shoko Shida's piece, Lonely Mountain for piano and percussion.>xv

SHA lot of people in your position—who are playing Stockhausen and all these really big European composers—wouldn't bother going to improvise with Geerken or Plank or do these things that are presumably less lucrative. I guess what I'm getting at is that I don't know of many other people who operated so thoroughly in so many musical idioms at the same time. Please tell us about the LP that you recorded with Ichiyanagi and Kosugi.

MRWell, in September 1975, we performed an outdoor concert as a trio in Hokkaido, an island north of Japan. As we came back to Tokyo after the gig, we thought, "Ach, it's too bad. That concert was so good, and the audience loved it, but the tape we made is not useable because it was outdoors." So, we called up the electronic studio at NHK, the Japanese radio-TV, and asked if we could come and repeat the performance. That's how a clean recording of this trio came about. Timo van Luijk has now reissued this LP on Metaphon.

SHWhile in Taiwan, you made several tape compositions. Can you say something about your compositional process and how you made artistic decisions in these unusual electroacoustic pieces like China Filch (1973)?

MRHuh, OK. [laughs] The first piece on the Taiwan Years CDxvi, Kagaku Henka, was made entirely at the electronic music studio of NHK in Tokyo in 1971 at the invitation of Takemitsu. It was made in Japan, but I was already living in Taiwan. China Filch was scraps of various recordings I made, running around with my little battery-operated reel-to-reel tape recorder. There's a marching band on the streets in Taipei, nature sounds, whatever. I mixed that in a studio in Taipei that, of course, wasn't as professional as the NHK studio in Tokyo. But it worked. The third piece, At Night, was music for a ballet piece by Lin Huai-Min for his dance group, the Cloud-Gate Dance Ensemble. Again, I worked in the simple studio in Taipei, put all the sounds together, made a master tape, and gave it to him. That was it. I'm not sure Lin Huai-Min ever used the music. This piece was made in 1978, close to the time I departed Taiwan.

SHWhat prompted you to leave Taiwan?

MRMy wife was teaching in Taipei and doing great, but she missed Japan. I think she went back there a little bit earlier than me, in the middle of 1979. I closed up the house, packed all my percussion instruments for shipment to Europe, sold all the furniture, and joined her in Tokyo in the fall. After some orchestra jobs with New Japan Philharmonic, we flew to Europe with our ten-month old baby, arriving just before Christmas, 1979. We came to Cologne where my composer friend Johannes Fritsch had already rented an apartment for us.

Fritsch wanted me back because he wrote music for a big ballet piece, Der Große Gesang, for only five players that included me on percussion. I don't know if there's a recording of it.xvii He gave me the score and all the details for this new piece and even found me a place to practice and to store my ever-growing collection of percussion instruments. The premiere was scheduled for the beginning of January 1980, so the intensive work began immediately after our arrival. It was a very successful piece that ran for more than two years at the Cologne Opera, plus many performances outside of Germany.

VdRHow did you balance your activities as performer and composer in those early years in Cologne? Around that time, you also started Asian Sound there to sell and distribute rare percussion instruments from Asia in Europe.

MRMost of my written compositions were done in the late 1960s and all through my Taiwan years in the 1970s. When I returned to Europe in 1979, I took a break of several years from composing scores. I spent my time with free improvisation, playing many concerts with [composer and musicologist] Dieter Mack, for example, while developing and sketching the scores for my long percussion piece Yuen Shan. I opened Asian Sound in 1980, but in the beginning, things were tough financially; there was no money at all. I started with a very small number of instruments: some tam-tams from China and bowls from Japan and Taiwan where I had some good connections.

One day, the WDR Symphony Orchestra called me because they needed on extra percussionist for a production of Prokofiev's Symphony No. 5. The WDR Symphony Orchestra has two timpanists and only two percussionists. I think five percussionists are needed for Symphony No. 5, so they would hire additional players. I went and played, and they liked my sound, so for fifteen years, from 1982 to 1997, I played as an extra with the WDR Symphony Orchestra. I needed the money. The orchestra percussionists would say, "What have we got here? Oh, a piece from Dieter Schnebel? Hit the tam-tam and dip it in water? Ah, call Mike, let him do that!" [laughs] But after 1997, I didn’t want to be an extra in a symphony orchestra anymore. My own music was taking all my time.

VdRNot long after you settled in Cologne, you also formed a short-lived percussion group, Ensemble Transit.

MRIn 1980, the WDR also asked me to put together a percussion ensemble to perform at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse. I called it Ensemble Transit because the players came from many places: Denmark, Berlin, etc. I think Christoph Caskel and I were the only ones from Cologne. I believe we only did two performances, the other one at the Kölner Schlagzeugfestival in 1981. It was just too expensive to organize more concerts, so I let it go and continued playing smaller scale concerts. I think my last performance with a large percussion set-up was in a trio in 2012. Since then, my activities have been mostly attending rehearsals and concerts of parts of Yuen Shan.

SHTell us about Yuen Shan.

MRWell, it's a composition for pre‐recorded sounds and live percussion that I started in 1972 and finished in 2014. Yuen Shan is the name of a mountain in Taipei where I spent seven years studying T'ai chi ch'üan every day. All four movements of the piece have Chinese titles. The work on Yuen Shan was long and difficult. I started with zero raw material. The portable tape recorder I obtained in 1970 had now come into intensive use. I recorded an immense amount of natural sounds: water, wind, an orchestra playing, etc. Then, in order to modify and combine the sounds, I acquired eight-track tape decks, echo, and modulation devices. The goal was to be able to present all four movements in three different ways: as an eight-channel recording for tape-only surround performances, which included the percussion parts; then as an eight-channel version without the percussion parts to be used as "tape accompaniment" when live percussion was available; and finally as a stereo version for the LP and CD productions. All four movements had a total length of more than 100 minutes.

The first performance of the third movement, I-Shr, was done 1998 with the Cologne Percussion Quartet. Other performances of parts of Yuen Shan happened in Berlin, Nuremberg, Mainz, and Cologne. All four movements were completed in 2014. I performed and recorded them in my studio over a period of a few months, and the result was published by Metaphon in 2015. I didn't use existing recordings since most of the movements were recorded by different percussion groups and there were permissions involved. And although the percussion quartets performed fantastically, some of the recordings were not usable, because of poor sound quality from performing in a church or outdoors. In 2022, all four movements of Yuen Shan were performed at the Ruhrtriennale festival by the Cologne Percussion Quartet.

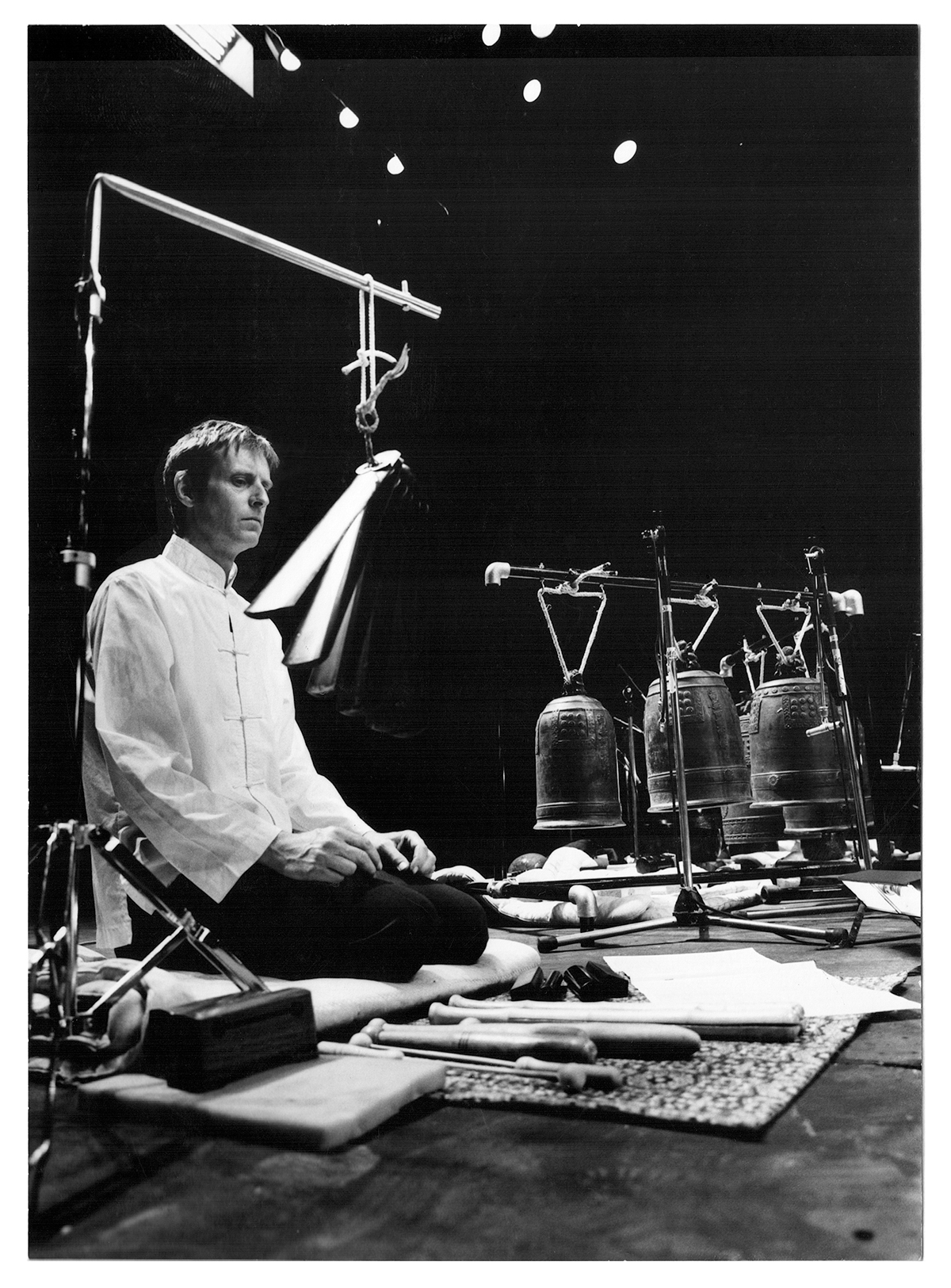

SHWe should also talk about your collaboration with Éloy, as he's an important part of your musical life. Your first piece together was Yo-In in 1980.

MRYes, the most important. When I first met Éloy, I felt that we were totally brothers. He felt that way too, and we got along wonderfully. My style of composition was very close to his. Now, how did Éloy pick me? Actually, he had travelled a lot to Asia before, to Japan and Indonesia, maybe through some connection with the French cultural institute who had organized a concert there for him. He knew this Japanese percussionist woman, and he had planned a new piece called Yo-In for her, a piece for tape and solo percussionist with lots of instruments—three hours and forty minutes long in four movements. But when they talked about it, they realized she would have to leave her engagements in Japan, come to Europe for several weeks, and every time there would be a concert in Europe, she'd have to fly over. Anyway, he eventually selected me to do it, which was much easier. We rehearsed Yo-In for about a month here in my studio in Cologne. For the first performance in Bordeaux, we needed a very big van to carry all these instruments. [laughs] We then played every night for a week at the Musée d'Art Moderne in Paris. [Iannis] Xenakis came four nights in row. He said, "Your piece is beautiful, but I'm not going to stay here for three hours and forty minutes! I'll come tonight for the first act, tomorrow for the second and so on." [laughs] [Olivier] Messiaen was also there. It was very successful, a big opening for Éloy. We played it in Liege, Amsterdam, Cologne, Bordeaux, Paris, Avignon, Japan, Strasbourg, and Warsaw. Since Yo-In came out really well, we worked on another piece together, Anâhatanxviii, which we performed in Bordeaux, Geeva, Paris, and Warsaw.

SHHow much was Yo-In a collaboration between the two of you, as far as the percussion part being written?

MRAh, very interesting. The percussion part was not written.

SHThat's what I thought.

MRÉloy described in words what he wanted me to do. When I did it, he said, "No, play more of the deep bells and gradually remove the high ones,” and things like that. We worked on the piece for weeks. We would do one act, and then I would clear out everything and set up for the second act. That's how we did it.

SHI read a quote recently where Éloy talks about trying to blend eastern and western sensibilities in his music, but in a way that is something entirely new, not just using this and that and putting it together.

MRYeah, it was new. His music was very free and unusual, and I think it hurt his performance chances in France because he was seen as a creative outsider. And don't forget that a performance of Yo-In involved only three people. There was Éloy at the mixing board with microphones everywhere, mixing and changing the sound live. I was playing the percussion, of course, and the third one was the lighting designer. It was a theatrical performance, and I had to change costume for each of the four acts.

VdRApart from your musical activities, you have also made many paintings, some of which are featured on your recent record releases. How did this interest come about?

MRWell, in April 1964, during my time in Petaluma, Partch and I made a visit to his old friend, Gordon Onslow Fordxix, who lived nearby. I cannot say that I studied with Ford, as I only spent one afternoon with him, but he showed me his "circle-dot-line" technique. I was fascinated and obtained the books he wrote about his work and studied them. I was inspired but had no time to practice. Decades passed, but I never forgot the visit to Gordon. In the mid-1980s, I wrote him asking about the possibility to purchase some paintings. He replied quickly by air mail with color photos. I ordered five larger ones and about seven small ones. Every day since, I spent time admiring them, and today, they are still hanging in our apartment.

Around 1990, I needed to relieve some of the pressure around the composition of Yuen Shan, a complicated process which took a lot of time. I bought a basic watercolor painting set and started a new phase in my life. From about 1990 to 2000, I created about thirty works from very small to very large, always remembering Gordon’s basic "circle-dot-line" structure. I only ever painted during vacations in our residence in the South France which has a large space under the terrace that I could use. I used the name "Wayne Jacob" on the backside of my paintings, which is my father's name; he had passed away in the late 1980s, just before I began painting. Using his name as a kind of pseudonym, I wanted to show my love and respect for him. I have hardly painted at all in recent years, except for some small works.

VdRAll in all, what has been your favorite music to play?

MRAs a player, I always looked forward to working with complicated and challenging percussion sounds and structure. But after my seventieth birthday, I knew that I no longer had the speed and virtuosity to keep up with the younger generation of percussionists. I can live with that, no problem. What disappoints me somewhat is the trend towards mostly loud and frenetic music in all instrumental and vocal areas, not just percussion. I wish that quiet and meditative music was more popular.

SHYou strike me has someone who followed the whim of doing the thing you felt like doing at any moment.

MRYeah, pretty much. I always looked for adventure.

iJack McKenzie (1930-) is Dean Emeritus of the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Illinois.

iiTom Siwe (1935-) was director of the percussion program at the University of Illinois, from 1969 to 1998.

iiiWerner Torkanowsky (1926-1992) was a successful German conductor in both the concert hall and opera house.

ivDanlee Mitchell (1936-) is Emeritus Professor of percussion at San Diego State University and served as Partch’s assistant from 1958 until Partch’s death in 1974.

vThe World of Harry Partch, Columbia Masterworks, 1969.

viEmil Richards (1932-2019) was a prolific vibraphonist and percussionist who performed and recorded extensively in jazz and pop music.

viiReleased as New Phonic Art 1973 / Iskra 1903 / Wired, Free Improvisation, Deutsche Grammophon, 1974.

viiiReleased as Ranta / Lewis / Plank, Mu, Metaphon, 2010.

ixMichael Ranta, MU V / MU VI, Asian Sound Records, 1984.

xRecorded 1975, released on Michael Ranta, Taiwan Years Metaphon, 2021.

xiNamed after the Heliopolis district in Cairo.

xiiThis is a numbered and signed edition of 25 copies released as The Heliopolar Egg, 2 Live Recordings of Concerts at Goethe Institute Cairo, Egypt ’72, USIS, Karachi, Pakistan ’75, Astres d'Or, 2021.

xiiiBruce Gaston (1946-2021) was a transplanted Californian who helped revolutionize Thai classical music by injecting it with Western instruments and forms, and who became a prominent and respected figure in Thailand as a composer, performer and teacher.

xivThe gayageum or kayagum is a traditional Korean plucked zither with twelve strings, though some more recent variants have eighteen, twenty-one or twenty-five strings.

xvReleased in Hartmut Geerken, The Osaka Fear Ear, R. Ling Press, 1986 and in Hartmut Geerken / Michael Ranta, The Heliopolar Egg, Qbico, 2010.

xviMichael Ranta, Taiwan Years, Metaphon, 2021.

xviiAvailable on Various artists, Ausstrahlungen, Koch Schwann, CD, 1996.

xviiiPremiered in November 1986 as part of a coproduction between the Paris Autumn Festival, the Bordeaux Sigma Festival and the ensemble Contrechamps in Geneva.

xixGordon Onslow Ford (1912-2002) was a British painter and the youngest member of the pre-World War II, Paris-based Surrealist Group. He left England for Paris, then on to New York as a wartime émigré. After a period working in a remote village in Mexico, he traveled up the West Coast to San Francisco, eventually coming to rest on a hilltop in Inverness on the Point Reyes Peninsula of California where he lived for his remaining fifty years.