If you’ve ever met David Dunn (b. 1953), then you’ve probably heard the story about being chased by a pack of lions in rural Africa or getting into trouble as a child for making cyanide gas. You can probably recognize the sound of snapping shrimp, know what to do when a grizzly bear shows up at the foot of your sleeping bag (go back to sleep) or how to diffuse a fight at a biker bar (offer a joint), and have heard of a flying termite in Zimbabwe that tastes like butter and honey. Dunn is full of not-entirely-believable stories and odd facts. His career as a composer has taken many forms—from staging multiple day-long outdoor desert performances to designing chaotic electronic circuits to recording the sound of millions of bark beetles chewing trees to death. At the center of it all is an individual deeply curious about the very function and meaning of music in human culture.

This article is an overview of Dunn’s work and several concepts that inform it. The first of three sections is about Dunn’s early environmental interactive pieces in which he staged encounters between humans and a particular environment. It also includes a discussion of Dunn’s study of linguistics in the early 1980s. The last section details Dunn’s exploration of autonomy and complexity through the construction of nonlinear circuits. The middle section highlights a transition period in the mid-1980s when Dunn shifts from creating environmental interactive pieces to modelling complex systems, and the metaphors he used to define his practice at this time, in particular “natural magic.” Ultimately, the focus is on what Dunn calls mind, a concept borrowed from anthropologist Gregory Bateson, which became the primary metaphor Dunn used to explain his work. Over the course of his career, Dunn expressed this concept using different terms. Mind, magic, deep structure, to list a few, are metaphors employed to articulate the ineffable, to explain the complex, often chaotic elements of living systems, which to Dunn point to a fundamental truth about how life, pattern, and meaning emerge.

Background: The Early Years

Dunn grew up in San Diego, California. His father worked as draftsman making technical illustrations for the military and his mother was a homemaker and artist—the two met in a painting class. His parents fostered a home environment where art, music, and creativity were encouraged and supported. Dunn was interested in drawing and painting, yet he claims that since his brother was the better visual artist, he focused on music instead. Dunn spent a great deal of time outside as a child. His family frequented the deserts and mountain ranges on the outskirts of San Diego County—in particular the Anza-Borrego Desert and Cuyamaca Mountains, which later served as the locations for several of his site-specific pieces. On such family camping trips, Dunn’s parents set up easels and made landscape paintings while he and his brother explored freely.

According to Dunn, he was a child prodigy; throughout his teens he played violin and viola semi-professionally in orchestras and ensembles. In his early teens, he became interested in twentieth-century music. Around this time, Dunn also started composing. His earliest pieces were emulations of serial and 12-tone techniques as well as works made using a Magnavox tape machine.

When Dunn was fourteen he saw a documentary about composer Harry Partch (1901–1974) on a local television station, which made a significant impression on him. In 1970, at the age of 17, Dunn attended San Diego State University with the intention of working with Partch, who was not actually teaching classes there at the time. Dunn dropped in on a class taught by Danlee Mitchell, one of Partch’s assistants, and told him, “I’m not interested in your class but I am interested in Harry Partch.”1 Dunn soon became one of Partch’s assistants, a position that he held for four years until Partch’s death in 1974. As Partch’s assistant, he did everything from grocery shopping and running errands to building, maintaining, and tuning Partch’s instruments. He also performed in the Harry Partch Ensemble from 1971 to 1981.2 From 1973 to 1979, Dunn worked as the Director of Electronic Music Studios at San Diego State University; in this position he developed specialized audio recording skills, which became central to his compositional practice.

Early Work: Environmental Interaction, Communication, and Language

To what extent might the technologies of communication, art and entertainment serve as ‘protheses’ that would provide us with experiences of wilderness that would not only enrich our human identity, but help us to preserve and expand the domain of the non-human world?3

Dunn’s early works engaged the spirit of place, composed for specific outdoor locations. Almost all employed technology—primarily recording and playback systems—at some point in the compositional process or during the performance as a means to access or examine environmental phenomena. Each piece is an experiment that tests how humans can connect to an environment using sound. In retrospect, Dunn came to view these pieces as an exploration of language and linguistic systems. To Dunn, language in its various forms indicates consciousness, and he became interested in exploring how seemingly different forms of consciousness that use different linguistic systems can communicate with one another or, at the very least, interact.

Why did Dunn compose pieces to be performed out-of-doors in the first place? As a too-smart-for-his-own-good young musician in his early twenties, who had just spent several years working with Partch, Dunn claims that he simply wanted to subvert concert hall conventions, and push composition to its performative limits.4 More importantly, these site-specific works stemmed from his experiences in the deserts, mountains, and forests of San Diego county as a child and teenager. The embodied knowledge of the outdoors formed the basis of Dunn’s intuition about the connections between music, human communications systems, and the patterns present in the non-human world. As he stated decades later, music is an evolutionary strategy by which humans “structurally couple with our surrounding environment.”5 It is important to note how Dunn’s use of the term “environment” changed throughout his career. Initially, the “environment” was more or less synonymous with “wilderness,” implying natural spaces that have nothing to do with humans or their creations. Initially, he wrote pieces specifically for sites with as little evidence of humans as possible. However, his definition later shifted to refer to a specific location that includes all things present, including what he calls, the manmade technosphere as well as the organic biosphere.

Dunn’s site-specific practice began with Nexus 1 (1973), which was performed and recorded at Hermit’s Gorge two miles down into the Grand Canyon. The score consists of graphically notated “sound gestures,” played by three trumpeters, who were instructed to sonically interact with the physical properties of the gorge. Dunn emphasized that the performers could activate and resonate “the extended reverberation and extraordinary spatial acoustics of the rock formations” present at the performance site.6 Although originally intended as an exploration of the place’s acoustics, as three crows began to participate by cawing in response to the trumpet players, the experience opened up broader questions about interacting with non-human lifeforms and entire ecosystems. It also led Dunn to the conclusion that humans had likely made music outdoors for much of human history, and that through such practices humans developed a sophisticated ability to interact sonically with their environment, a skill that humans seem to have lost.

Dunn addressed the potential for interspecies communication directly in Mimus Polyglottos (1976). In this work, Dunn and his collaborator Ric Cupples played an audio recording of a square wave oscillator to a mockingbird in order to observe the bird’s ability to mimic an aperiodic stream of electronic sound. Their goal was to create “an audio stimulus that would engage the birds but also challenge their ability to mimic."7 It took Dunn and Cupples months of experimentation, observing and sonically interacting with mockingbirds in Dunn’s neighborhood near Balboa Park in San Diego to settle on the appropriate stimulus—according to Dunn, they used a square wave oscillator because square waves are notoriously difficult for the human vocal apparatus to reproduce. Dunn thought of the piece as an attempt to develop a linguistic encounter between two species: “Our interest was not only in seeing how we could push that ability in terms of the actual sounds which the birds could mimic, but more significantly to generate a linguistic interaction.”8 Ultimately, Dunn was struck by the mockingbird’s willingness to engage creatively with the “artificial” (i.e. non-animal) electronically generated sound.

Subsequent pieces including Skydrift (1976–1978) and Entrainments 1 & 2 (1984–1985) further explored the capacity for humans to interact with larger environments or ecosystems. Dunn created complex interactive systems that consisted of electronically generated sound, acoustic/human-made sound, and recording and playback devices. In such pieces, humans are a critical node in the circuit. They listen to and sonically respond to their surroundings, acting as a kind of feedback mechanism in the system. The element of feedback is at the crux of the interactions that take place, for the ability to cultivate a collaborative dialogue demonstrates the complex properties of the human-environment relationship.

Skydrift is scored for ten voices, sixteen instruments, speaker network, and four-channels of electronic sounds. The performance took place in Little Bear Valley in the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California. The vocalists stood in a circle while the instrumentalist slowly walked outward in a larger circle—responding to both “information from the environment” and a graphic score—until they reached what Dunn called the “perimeter of audibility from the center of the space.”9 All of the performers were amplified, and the electronic sounds consisted of sine wave generators that were meant to “resonate the space.”10 The full score includes not only the graphic notation used by performers and a description of the performance, it also contains interviews with each of the performers, which make up the bulk of the 85-page score.

Like Nexus 1, Skydrift is a sonic exploration of place, yet it also stems from an interest in how humans employ language and Dunn’s “desire to learn to communicate with the external world.”11 The goal of the piece was “to communicate something of the non-human world through showing how a part of humanity confronts that world; and to demonstrate that we converse with the earth not only through the behavior which we manifest by our physical actions, but the language which we use to express how the earth controls that behavior.”12 With Skydrift, he explored how human language, which is culturally determined, defines a particular relationship to the earth. The terms devised to describe aspects of the earth carry with them certain connotations indicating the value of particular environmental elements in culture. In the case of Western cultures in general, Dunn believes that language separates humans from the earth. With Skydrift, he began to grapple with how, over time, human linguistic systems take on aspects and structures of the environmental systems which they attempt to describe, allowing for some synchrony or communication between humans and their non-human surroundings.

The Construction of Language and Animal Communication

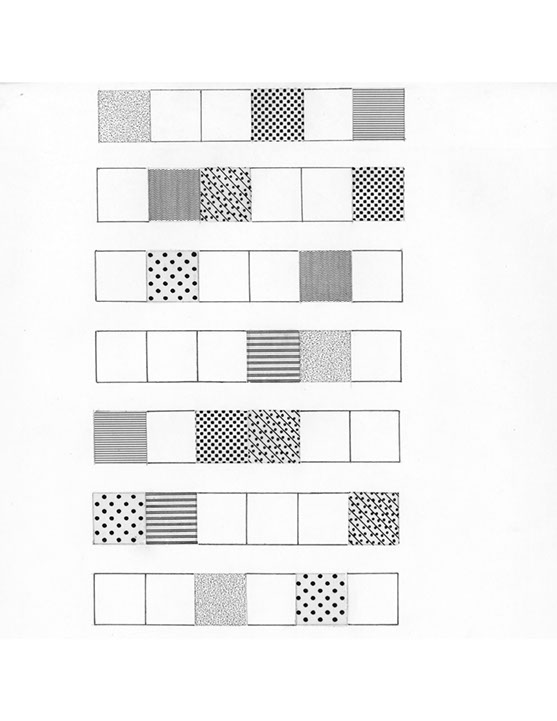

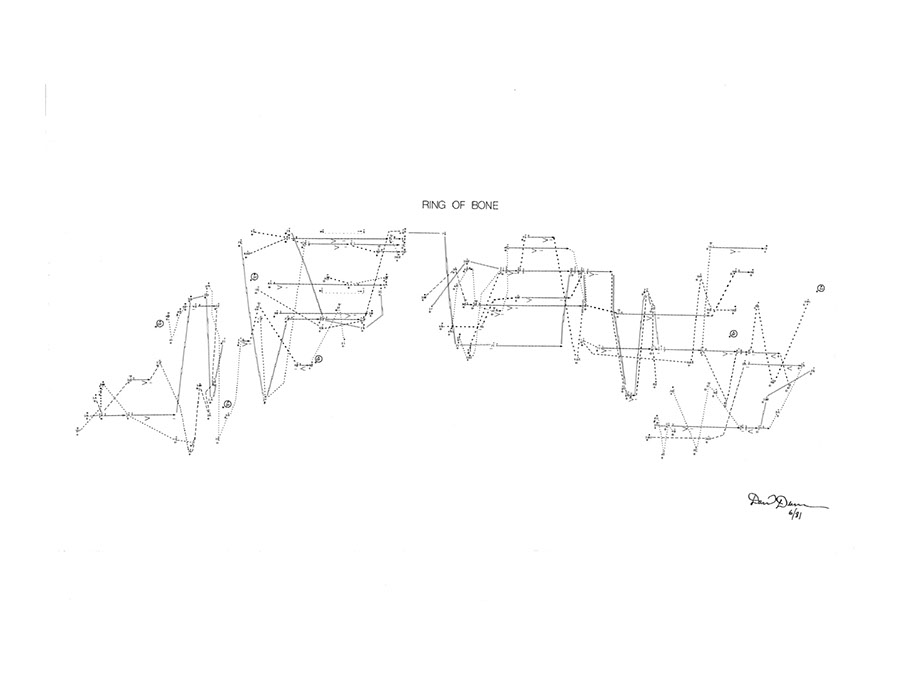

In the early 1980s Dunn made a concerted effort to deepen his understanding of language and linguistic systems; he believed such knowledge would shed light on his sonic interactions with the non-human world. From around 1979–1980 he studied with composer Kenneth Gaburo.13 During this period, he wrote pieces that explicitly explored linguistics, including Madrigal (1980) and Ring of Bone (1981). Environmental interaction was not a part of the pieces, which were written with a more traditional concert setting in mind. Dunn’s approach to notation however, was innovative; he meticulously designed hand-drawn graphic scores.14

Madrigal, subtitled “The Language of the Environment Is Encoded In the Patterns of Its Living Systems,” focuses on the relationship between human language and animal communication. The work is based on a one-minute environmental recording, which Dunn transcribed—including birds, insects, and airplanes—into International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) notation. A performance of Madrigal consists of recitations of the IPA transcription accompanied by an altered version of the original environmental recording.15 The title of the piece refers to the tradition of secular polyphonic vocal works that date back to the Renaissance period in which commonly employed imitation of birds, insects, animals, or even atmospheric elements in service of expressing a text.

In Ring of Bone, Dunn further experimented with phonetic notation, communication, and the performance situation. The score consists of “spatial” notation: phonemes are arranged in space, with the vertical axis representing pitch and the horizontal axis representing time. Ring of Bone is to be performed by ten male vocalists, who cycle through the notation ten times, rotating so that each vocalist performs each part once, and the cycles get proportionally shorter throughout the piece. As the vocalists articulate the notated phonemes, words emerge out of the totality of the ten voices. Dunn thought of this approach as biological, with a score “that results from a sort of ‘genetic engineering’ of language, a recombinant linguistic DNA constructed of phonemes.” He explains, “I analyzed a text in precise detail and then constructed the composition out of pattern relationships embedded in macro- and micro-levels of structure.”16 Throughout the piece the vocalists also gradually move, while maintaining symmetry, from a dispersed circle around the audience, through the audience, to a small closed circle.

To Dunn, linguistics and communication explain the substance of human interactions with each other and their surroundings. His compositions were premised on the conviction that music is more closely related to animal communication than human language, and that there is great potential to use music as an interactive language. He asserts that “the importance of such an interaction between the study of music and the study of animal communication signals addresses the very issues of what might distinguish human consciousness from that of other animals.”17 The study of language not only shed light on his previous work; the linguistic nature of interaction, communication, and consciousness also became a central, although not always explicit, principle in all of his subsequent works.

Entrainments 1 (1984) & Entrainments 2 (1985)

In the mid-1980s, Dunn extended the idea of consciousness beyond animals and humans to whole ecosystems or environments. To Dunn, language broadly defined, is an indicator of consciousness. He explained: “What I propose is the creation of actions which reinforce the inclusiveness of that larger systemic mentality resident in the interactions of environment and consciousness. This, of course, borders on investigations of consciousness and therefore the origins of language.”18 Each piece is based on stream-of-consciousness descriptions made by performers as they explore the performance site and its acoustics. The pieces demonstrate a correspondence between patterns present in disparate environmental phenomena and human language or actions.

Entrainments 1, subtitled “Enfolded Traces of Environment’s Memory Revealed in Holonomic Space,” is to be performed in Azalea Glen, in the Cuyamaca mountain range where Dunn camped with his family as a child. Each element in the compositional system reinforces the essence of place and the patterns present in Azalea Glen. As Dunn later explained, “Beyond its descriptive properties [Entrainments 1] represents the interactive tracings of the mentality implicit to a specific geographic location in that every aspect of the work was either realized in or extracted from that location.”19 The piece is premised on an initial interaction: a square-wave oscillator was projected into the performance site to excite the acoustics and stimulate a response. This encounter was recorded and then altered for use in the eventual performance. Additionally, prior to the performance, performers made audio recordings of their stream-of-consciousness observations of the performance site and their experiences in it. These recordings serve a function that parallels that of the performer interviews included in the Skydrift. In the Entrainments series, however, they are explicitly incorporated into the performance of the piece. Dunn combined all of these recordings using a pitch-to-voltage converter, “such that the speech sounds became tracings of the environmental sounds while modulating the overall timbral spectra of the environment.”20 In a further articulation of place, Dunn played four layers of these manipulated recordings back into the original space.

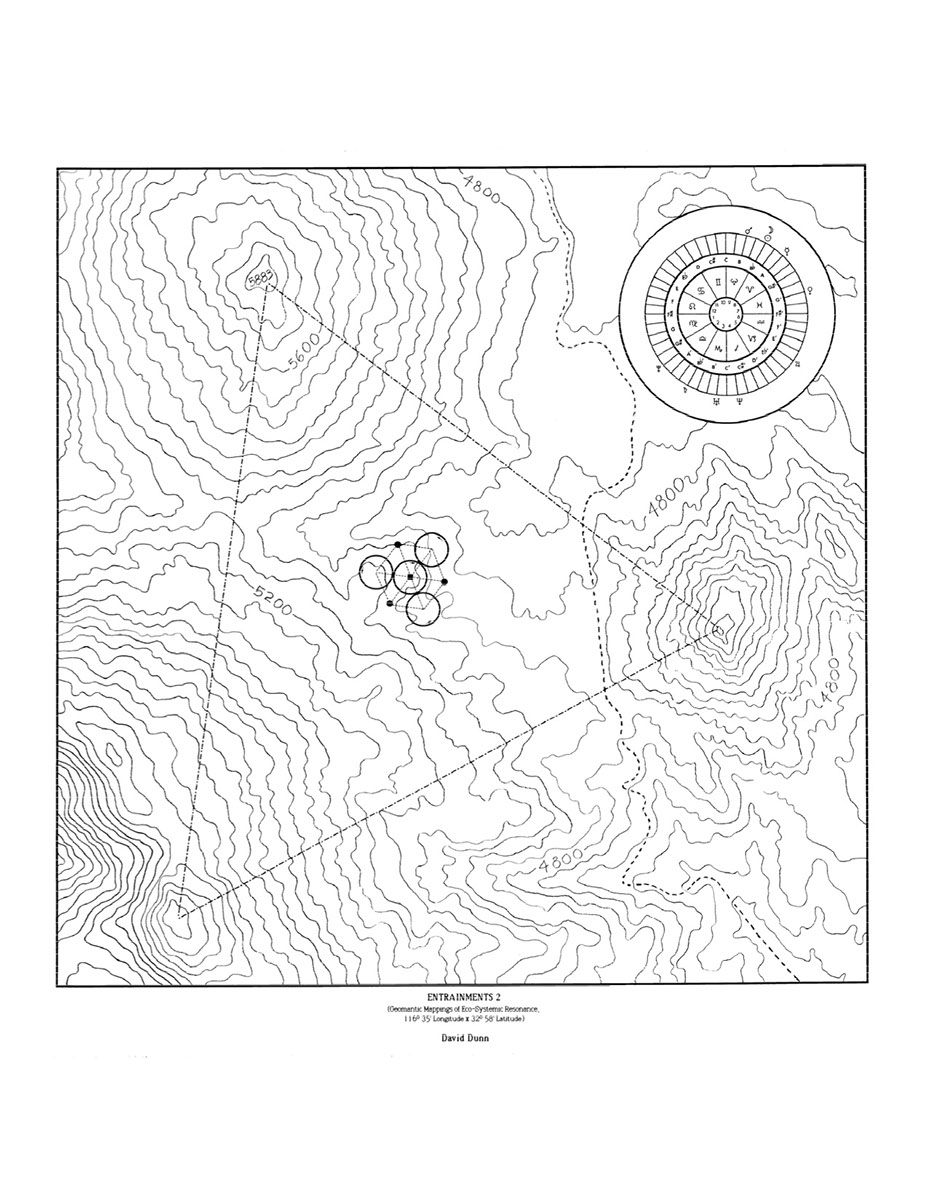

Entrainments 2, subtitled “Geomantic Mappings of Eco-Systemic Resonance” was also composed for performance in Azalea Glen. Like Entrainments 1, the work is based on an initial interaction: three performers recorded stream-of-consciousness observations of their surroundings on three mountain peaks that overlook Azalea Glen. In the performance, these recordings—subsequently mixed with drones that were constructed using a simple sonification of astrological data that corresponded to the site—were played back in a triangular arrangement that aligned with the mountain peaks on which they were initially recorded. The three performers walked in circles around the space carrying square-wave oscillators with amplification, which they manipulated “in a process of conceptual tuning to the overall sound environment.”21 Another performer walked in the opposite direction carrying a microphone and binaural recording device; the input of the mic was sent to a digital recorder and speaker system that sampled and played back three-second clips of the input, and the binaural mic was used to record the entirety of the performance. According to Dunn, “The primary task was to somehow define nodes of interaction within the changing soundscape.”22 In Entrainments 2, Dunn also highlights the principle of emergence, “through a complex process, patterns may arise that appear to transcend their generative agents.”23 Emergence of patterns became evident when observations made in the stream-of-consciousness recordings paralleled events that occurred during the performance.

The Entrainments series established a set of relationships between humans, technology, and the non-human world. Dunn constructed complex systems in which each node had a feedback mechanism that allowed participants to observe and experience how each element in the system (human, environmental, technological, or otherwise) could communicate in meaningful ways. In summarizing this stage of his practice, Dunn stated:

My idea of environmental language is an experiential, dynamic process that explores whatever tools and metaphors are available toward a greater understanding of the profound interconnectedness between sound, language, and the environment...these linkages suggest an essential role for the evolution of sound art and music: the creation of human actions that reinforce the inclusiveness of the larger systemic mentality resident in the interactions of environment and consciousness.24

This quote also indicates Dunn’s belief that music can be a tool for human integration with their environment. He proposes the use of sound and technology as a means to establish meaningful relationships between humans and their non-human surroundings.25 To Dunn, an intimate connection with the non-human world is a crucial aspect of what it means to be human. His early environmental interaction pieces are structured in such a way as to emphasize and demonstrate how humans are a part of greater ecosystems, not separate from what is culturally considered “nature.”

II. Natural Magic, Mind, and the Sacred

I am applying current technology towards a rediscovery of ‘natural magic’.26

In the mid-1980s Dunn’s work began to shift away from the performative environmental interaction pieces. At the time he was vice president of the International Synergy Institute, a Los Angeles–based consulting firm. In this role, he acted as a liaison between cutting-edge and fringe academic research—which informed his compositional practice—and the entertainment industry. Dunn also spent a great deal of time, often under the auspices of the Synergy Institute, with mathematician Ralph Abraham and ethnobotanist Terence McKenna, who had a significant influence on him. Dunn recalled a conference organized by McKenna and biologist Rupert Sheldrake at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur to Gaburo in a letter dated June 26, 1986. Dunn described himself as in “the middle of the ‘heretic priesthood.’” This observation was no doubt fueled by the late night, drug-addled soaks in Esalen’s hot springs surrounded by his male peers, including Abraham, McKenna, and Sheldrake. He continued:

Rupert Sheldrake and Terence McKenna focused some rather charming effort in demonstrating that what I was doing was in the very long tradition of western sympathetic magic (Campanella, Ficino, John Dee) which tried to use language and technology to perform magic by conjuring ‘elementals’ as a ground of power.

So this got me to thinking about what it means to be an ‘emergent magician’ which is what Sheldrake called me. I thought all of this was very amusing since it was done in a spirit of great fun but since then I’ve given the idea more thought and realize that they were relatively serious and probably quite correct in calling what I did (the environmental interaction projects) ‘magic.’ There were two essential tenets of the magical world view: 1) the assumption of a fundamental interconnectedness of all things; 2) the assumption that we create new experiences through manipulation of reality which access and describe a larger consciousness beyond that of the social consensus.27

Natural magic or Renaissance magic became Dunn’s default metaphor to describe the complex systems he created and their emergent properties. This is clear in his 1989 statement: “I think of [my work] as applying current technology towards the rediscovery of natural magic. This is a great tradition that uses elementals as a ground of power. In my case it is a marriage of music and electronic technology which serves to invoke an archaic relationship to nature.”28 To Dunn, Renaissance magic consisted of ways of using language as a means to understand and describe the complexity of the world as it was observed and experienced. Magic has to do with the inability of language to fully describe one’s experiences; it embraces subjectivity, that each person’s experience of the world is slightly different. The mystical or magical is some ineffable thing that emerges in the gaps between people’s shared experiences. Rather than seeking objective truth, Dunn advocated for idiosyncratic, individual experiences as the locus of truth; as he wrote to Gaburo: “Magic says that observer/observed relationship is the only system we have.”29 Dunn’s interest in magic partially stems from a deep suspicion of modern science and its methodologies as well as its separation from artistic practices. He states, “Before art and science became distinct (and often mutually contemptuous world views) there was magic. The scientific view makes art necessary. Art is magic robbed of its power by science.” Around this time, Dunn began to view his compositional practice as an idealized integration of art and science.

By describing natural magic as an “archaic systems of balance” in which humans “see ourselves as an intrinsic part of a larger system,” Dunn touches on the notion that grounded his early work: in a previous time, humans lived a more complete, balanced, existence. Aspects of this integrated relationship have been lost, which might be evident in the worldview of the natural magician.30 With pieces like Skydrift and Entrainments 1 & 2 Dunn acted as a Renaissance magician, intuitively constructing complex interactive systems between humans and their environment through sound. He observed patterns and indications of deep structure that emerged out of these systems, and at this point, used the term “magic” to describe them. In Skydrift, each participant’s particular experience is highlighted, and their individual perspectives are brought together in the score. Along with the actual performance, which included electronically generated sound, voices, and instruments in response to the environment, as well as the environmental reverberations that resulted in the performers actions, a whole composition emerges out of these fragmented elements. Dunn explains, “the interviews have served to unify the composition’s parts by describing the diversity of the participant’s experiences. Thus, the composition is now inclusive of not only the complex sonic event but also information about the conditions necessary for its existence."31

The subtitle of Entrainments 2 unequivocally points to natural magic in the use of the term “geomancy,” a Renaissance divination method. Dunn describes the principles that undergird this piece, geomancy and feng shui, as “archaic philosophical traditions.” He was particularly interested in the aspects of symmetry and balance present in both traditions. Symmetry was a central component of both pieces in the Entrainment series; in Entrainments 1, Dunn conceived of the manipulation of recorded material as “symmetrically folding one layer into the next to “embed a deeply palindromic structure at all levels.”32 A sense of symmetry was essential to the spatial arrangement of Entrainments 2. In the score, Dunn stressed the importance of alignment of mountain peaks in the Cuyamacas where performers recorded their stream-of-consciousness observations, as well as the placement of the systems that played back these sounds, and a balanced relationship between the performers at Azalea Glen.

The metaphor of magic is relatively short-lived for Dunn; it is eventually channeled into and subsumed by cybernetic anthropologist Gregory Bateson’s (1904–1980) concept of mind. Dunn cites Bateson’s definition of mind:

I suggest that the delimitation of an individual mind must always depend upon what phenomena we wish to understand or explain…The individual mind is immanent but not only in the body. It is immanent also in pathways and messages outside of the body; and there is a larger Mind of which the individual mind is only a subsystem. This larger Mind is comparable to God and is perhaps what some people mean by “God,” but it is still immanent in the total interconnected social system and planetary ecology.33

In this quote, Bateson describes mind as a hierarchy of interrelated subsystems, from the simplest circuits that make up individual living things to the larger systems of which all individual living things are a part. Mind is distributed and emergent, residing not in one location, but rather in and between many—the pathways within and beyond the body. Bateson draws connections between the mechanisms that govern both electrical/mechanical and biological systems, which suggest an affinity with Dunn’s understanding of the complex systems he devised.

Although Dunn refers to Bateson as early as 1983, mind did not become the dominant metaphor for several years, and it is likely that Dunn was interested in Renaissance magic and mind for the same reasons: as a way to understand complex and ineffable patterns that are difficult to explain with conventional math and science. In retrospect, Dunn came to think of his environmental interaction pieces as engaging with Bateson’s fabric of mind. Dunn states, “I think it is fairly obvious how significant Bateson’s ecological model of mind as emergent to basic information systems has been towards how we might redefine our relationship to the non-human living world. It is probably not so obvious how relevant it is to understanding our future relationship to our networked technologies and machines.”34 Importantly, Dunn believes that “music is perhaps one of the best means we have for thinking about this fabric of mind that resides everywhere.”35 For Dunn, music is an activity through which humans exercise the capacity to participate in a larger fabric of mind, and as such it a skill that is necessary to human survival.

III. Autonomy, Chaos, and Models of Mind

I can’t think of anything more natural than the sound of moving electrons.36

The mid-1980s were a self-identified transition period in which Dunn reflected on his previous work and began to move forward with a new set of tools and concepts, exploring Bateson’s concept of mind through the tools of nonlinear science and the concept of autonomy. Nonlinear science is used to study systems that cannot be broken down into smaller parts, but rather must be studied whole, because the constituent parts interact and behave differently in conjunction than in isolation. It provided Dunn with a scientific paradigm to describe how seemly distinct systems are interconnected and interdependent—in other words, it is a mathematical formulation for understanding the distributed, emergent structure of Bateson’s “ecology of mind” and Renaissance magic. As a result, Dunn’s work shifted away from interacting directly with environments and towards modeling them by building nonlinear systems using electronics. This practice, which began in the 1980s and continues to the present, consists of a variety of forms: from sonification of chaotic attractors to complex analog feedback circuitry to digital patching systems.

The concept of autonomy became central to Dunn’s understanding of mind. For Dunn, autonomy is related to a number of terms, including emergence, self-organization, pattern formation, fractal self-similarity, chaos, and complexity. He applies the term autonomy equally to many phenomena: the self-organizing behavior of frogs chirping in chorus, the sound of electrons zipping around an electronic circuit, the mathematical structure of a recursive fractal system, and even the organization of our own perceptual mechanisms. These phenomena are connected, sharing a deep fundamental structure: autonomy. Dunn’s understanding of autonomy is informed by Francisco Varela and Humberto Maturana’s notion of biological autonomy, which Varela defines as the “self-asserting capacity of living systems to maintain their identity through the active compensation of deformations.”37 Autonomy is the condition of being separate, or distinct from the external environment. Considered in terms of Bateson’s “ecology of mind,” autonomy is the defining feature of an individual mind that makes it a distinct subsystem from the larger fabric of mind. Autonomous systems are characterized by having their own internal organization, separate from that of the external environment. According to Dunn, autonomy arises through emergence or “a type of ontological bootstrapping.”38

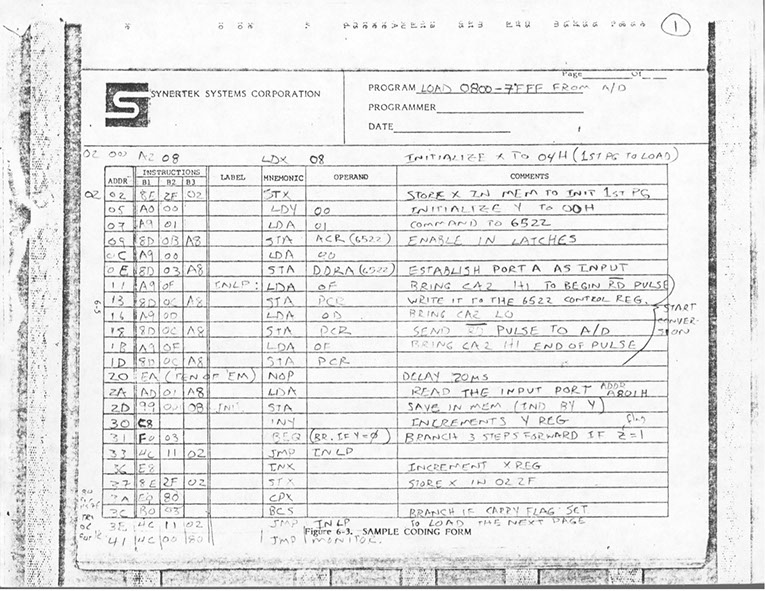

Dunn first experimented with autonomy in Simulation 1: (Sonic Mirror) (1986), “a stationary cybernetic sound sculpture capable of processing acoustic data within an outdoor environment.”39 Composed shortly after Entrainments 1 & 2, Simulation 1: (Sonic Mirror) used similar sampling technologies—a custom-built portable digital sampling and playback system paired with a pitch-to-voltage converter, enabling the environmental audio to control an electronic synthesizer.40 Dunn considered the interaction between environmental sound and the electronic synthesis systems as “pattern tracings of the environmental source.”41 He explains in the score that “it is the environment that is instructing a variety of systems how to transform the various environmental sound events.”42 The sounds are controlled by and therefore reflect features of the environment—as the title indicates, in a kind of sonic mirror. Dunn hoped the piece would be an “autonomous system structurally coupled to its surrounding environment in a manner that might allow for learning between components.”43 Here learning refers to the emergent properties that occur when two systems interact and how they adapt to one another, and in later writings, the term “emergence of mind” is used instead. Simulation 1: (Sonic Mirror) was not entirely autonomous—Dunn controlled the sampling system in performance, but this established a line of questions about how to design autonomous systems, motivating much of his later work.

Nature and the Sounds of Chaos

In the 1990s, Dunn began to experiment with chaos theory as a tool for designing autonomous systems. Chaos theory is a branch of nonlinear science that became popular in the 1980s as a way to explain structure in complex systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions, meaning small changes to the system at one moment can evolve into large changes over time—colloquially referred to as the “butterfly effect.” Scientists employed chaos theory to find and explain structures in natural phenomena that were previously considered beyond the purview of traditional physics.44 During this period, Dunn also spent a great deal of time listening to and recording natural environments, and he intuitively recognized chaos in the patterns he heard in natural soundscapes. This is evident in the 1999–2000 score Pleroma SERIES in which he states: “These [chaotic] sounds excite me because they are so physically reminiscent of the global sound behaviors that emerge from natural habitats such as swamps, forests and oceans.”45 The 2010–11 score for Thresholds and Fragile States offers an interpretation of the night sounds of the Atchafalaya swamp using terms borrowed from chaos theory. Dunn described the swamp soundscape as a fractally-delineated field of interlaced non-linear sources driven into global patterning by an underlying emergent logic:

One of the most striking features of this sound world was the abrupt transition between distinct collectives of sound makers. One group would hold center stage for hours and then suddenly fade to silence. Within minutes a whole new cast of sonic actors replaced them. The dynamic quality of these dense soundscapes, with their fantastic spatial motion, impressed upon me a sense that—beyond the communicative agenda of individual living sound generators—there was some underlying emergent logic at work to drive them into a global patterning. It was as if there were multiple chains of communication linking a fractally-delineated field of interlaced non-linear sources. These communicative chains not only extended outward in all directions but also up and down levels within a potentially infinite array of organizational hierarchies.46

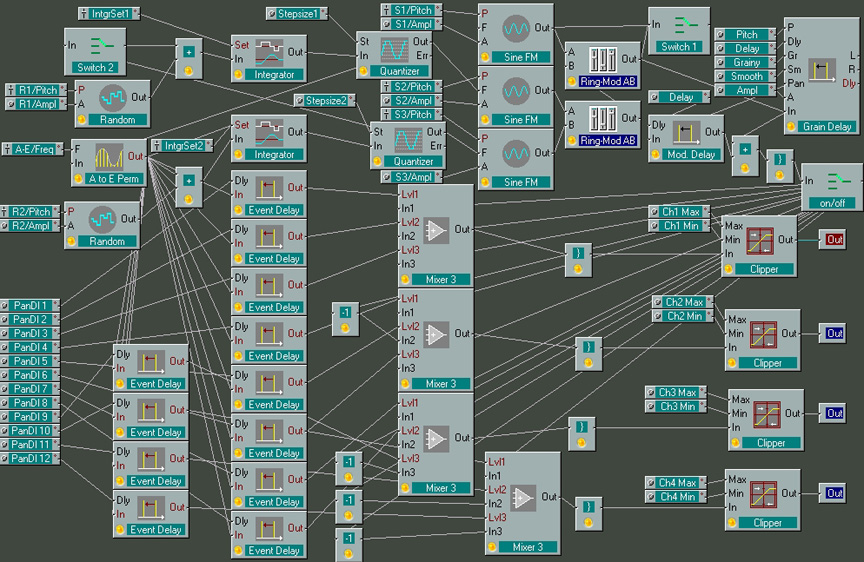

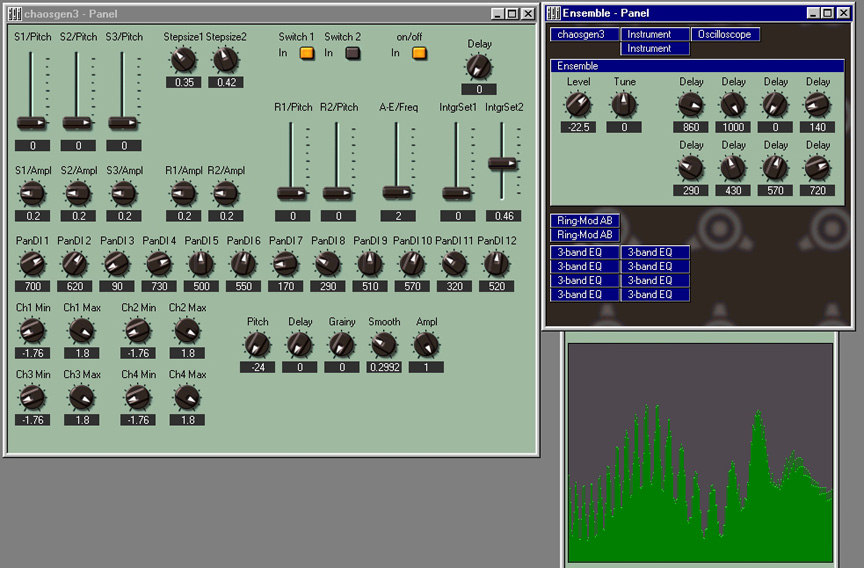

With Pleroma SERIES (1999–2000), Dunn explored the capacity of chaotic systems to produce emergent structures over time. In this piece, multiple chaotic circuits are connected together, each modulating one another simultaneously.47 In isolation, each of the chaotic circuits produces its own sound patterns, but when connected, new, complex patterns of sound are heard. These new sounds are not exhibited by any single circuit in isolation, but form as the result of the constant push and pull between circuits. Since the patterns are a product of the system of connections between oscillators, they are called emergent. In the score, Dunn compared the piece’s generative structure to a “genetic code,” a metaphor also used to describe Ring of Bone, and he explained that “the emergent complexity results from the dynamical attributes of cross-coupled chaotic states interacting in a multi-dimensional phase space.”48 Dunn describes the “behaviors” of such systems, referring not just to the particular sounds and pattern of sounds produced, but also how the systems respond to parameter changes. For Dunn, systems are not characterized just by the sounds they make at any given moment, but by their capacity to respond to changes from their external environments.

With Pleroma, Dunn stated that his role as the composer was “to explore various regions of these behaviors in a manner analogous to the exploration of a physical terrain.”49 He controlled a network of gates, or virtual software switches. Opening and closing the gates changed the coupling between circuits, producing different kinds of emergent behaviors. Dunn highlighted the unpredictable, self-organizing character of chaotic systems: “While I can influence the complex sonic behaviors, I cannot control them beyond a certain level of mere perturbation, the amount of which is constantly changing.”50 Dunn rejected the idea of composition as specifying fixed detail in favor of an approach that was more sympathetic to the autonomy of the system. He described the structure of the composition as improvisatory: rather than force the sounds to follow a precomposed path, he gives the system room to assert its own agency. Dunn hoped to build systems that he could not fully control, requiring the performer to learn to work with them.

The agency or unpredictability of Dunn’s chaotic systems comes not from randomness but from their extreme sensitivity to changes so small that they are beyond human capacity to control or even measure. In this sense, Dunn’s use of chaos is categorically different from the work of composers who used random processes as a source of uncertainty. For instance, John Cage’s (1912–1992) use of the I Ching or Iannis Xenakis’s (1922–2001) stochastic processes. Dunn’s chaotic circuits are more akin to works driven by complex feedback structures. For example, David Tudor’s (1926–1996) massive systems of electronics, Bebe and Louis Barron’s (1925–2008; 1920–1989) circuits based on cybernetic principles, or Gordon Mumma’s (b. 1935) cybersonic console. Dunn’s recognition of this distinction is evident in Pleroma’s dedication: “To the memory of David Tudor.”51

Designing Autonomy

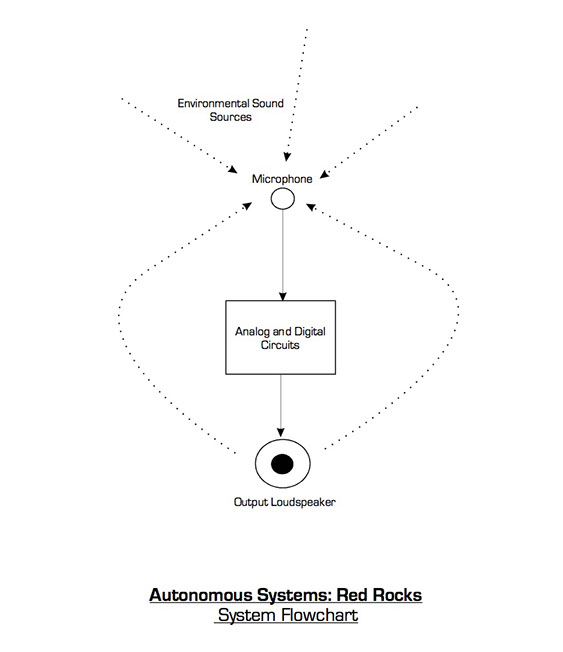

Dunn continued to develop his ideas about autonomy with the series Autonomous Systems (2003, ongoing). One work in the series, Red Rocks (2003), is an outdoor, site-specific sound installation in which an electronic system interacts with the external environment through sound, similar to Simulation 1: (Sonic Mirror). In Red Rocks, however, the electronic system is fully autonomous, driven by self-organizing nonlinear behaviors of networked chaotic oscillators. Dunn allowed the system to run on its own in performance without his control. As he explained, “The resulting soundscape is a combination of self-organizing autonomous machine-based structures and processed samples from the external world that interact and influence each other.”52 Other works in the series establish interaction between networked computer systems. In one instance, Dunn coupled together three computers that ran independent copies of the same sound processing software in a feedback network such that each computer modified and was being modified by all of the others. In Autonomous Systems humans are no longer a central node in the system but separate observers. This is in sharp contrast to Dunn’s earlier environmental interactive pieces in which the individual experience of the performer was central. The intention behind Autonomous Systems was to juxtapose two entirely non-human autonomous systems in a way that might “allow for the emergence of mind.”53

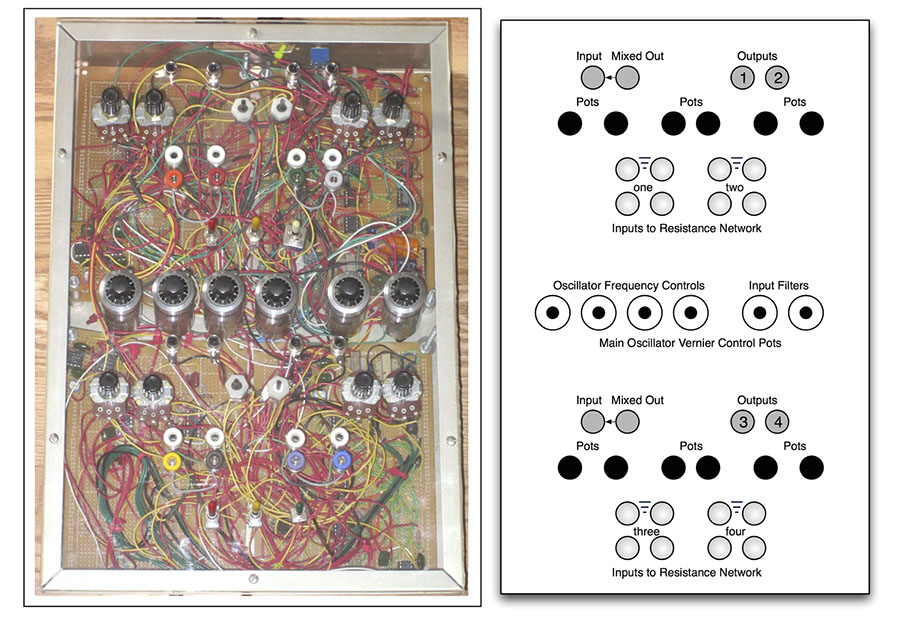

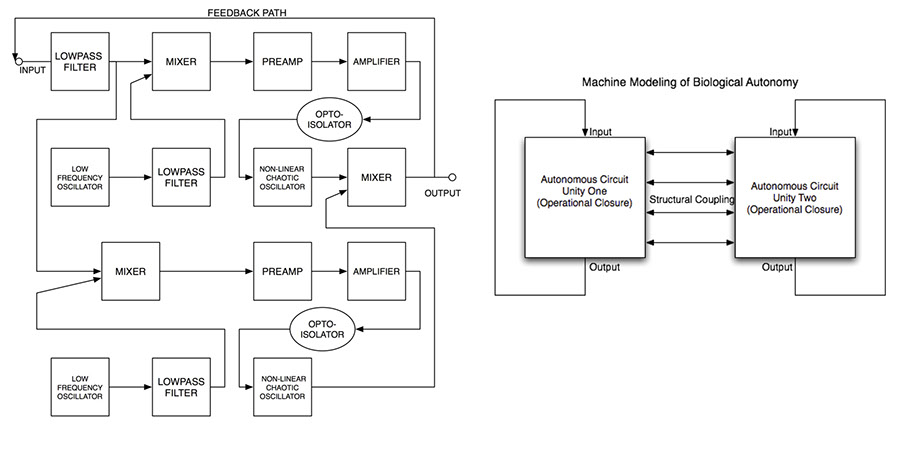

Extending Pleroma and Autonomous Systems, Thresholds and Fragile States (2010–2011) is perhaps Dunn’s most rigorous formalization of autonomy. The work is a systemic model of Varela and Maturana’s theory of autopoiesis, which describes how autonomous systems maintain and produce themselves. Built entirely out of analog circuitry, the piece consists of networked chaotic nonlinear oscillators arranged hierarchically, reflecting Bateson’s hierarchical structure of mind.54 Contrary to common audio oscillators, which typically generate one periodic waveform, chaotic oscillators are capable of generating a wider range of waveforms, from simple and periodic to complex, quasi-periodic or non-periodic noise. Moreover, small changes to control parameters can produce abrupt, drastic, and unpredictable changes in the oscillator waveform and frequency.

Central to Varela and Maturana’s theory is the concept of structural coupling. Since autonomous systems are closed, or separate from their external environments by a boundary, information does not pass from one system to another through the boundary. Rather, autonomous systems interact through structural coupling, influencing one another by causing internal structural changes called perturbations. In Thresholds and Fragile States, the oscillators are closed in the sense that each constitutes an individual feedback circuit. They are structurally coupled through a “shared resistance network,” which means that the oscillators do not share signal through inputs and outputs but rather perturb one another by adjusting the internal resistance value that determines the oscillator's state, affecting both its frequency and timbre. The resistance network allows each oscillator to remain closed to each other while still allowing them to be interconnected, the defining mechanism of Varela and Maturana’s theory. The term structural coupling appears throughout Dunn’s writings, as early as the score Simulation 1: (Sonic Mirror), and he experiments with the concept in a variety of forms over the course of two and half decades before formalizing it in the notion of a resistance network in Thresholds and Fragile States.

In Thresholds and Fragile States and other autonomous works, the function of the composer becomes that of designing a generative system from which music emerges. Dunn explains, “Rather than musical composition as the specification of fixed details of structure over time, it now becomes the design of a generative system of sufficiently high-dimensional complexity from which rich sonic behaviors can emerge.”55 Dunn associates generative music systems with a desire to subvert his individual self-expression. This impulse is in many ways the same impulse experienced by earlier generations of composers, but filtered through a different cultural zeitgeist. For example, Cage also looked to nature for alternative sources of structure, organization, and beauty, as a result, he employed the I Ching reflecting the prominence of Eastern philosophy in the public conscious. Dunn’s use of autonomous and chaotic systems coincides with the emergence of complexity science.

The Magic in Nonlinear Science

Dunn considers Thresholds and Fragile States a model to explore the structure of living systems. The circuits “articulate an underlying assumption of biological autonomy through a basic design implementation” and should be “understood as a metaphoric machine expression of the autonomy of the living systems rather than as merely information processing devices.”56 The circuitry is “a tool for the exploration of dynamics that help weave sounds together in the natural world,” and he explains that “comparisons and interactions between these natural and artificial systems might shed light on how similar dynamical properties might be operating at their generative levels.”57 Dunn’s approach to modeling shares an affinity with early cyberneticians, such as Ross Ashby or Walter Grey who, believing that the same principles govern all behavior, whether in biological lifeforms or machines, studied principles of behavior by building basic machines to embody them. Dunn claims that his working method “straddles artistic and scientific categories of explanation,” combining both analytic thought, and artistic ingenuity and performance.58 Thresholds and Fragile States extends Varela and Maturana’s theories by instantiating, in physical form, a model of their ideas. The piece also extends a tradition of electronic music in which composers designed complex feedback circuitry in order to produce unpredictable emergent results removed from composerly intention.

What is learned through building and observing artistic models that instantiate basic principles? Dunn believes that artists and musicians possess a body of knowledge that can contribute to the understanding of complex systems. There is something magical about artists’ abilities to design, build, and interact with complex systems. Predicting and controlling the emergent behavior of large chaotic oscillators only started to be understood in scientific communities in the late 1980s—prior it was an intractably complex problem in most cases. Musicians, however, fascinated by complex feedback networks long before they came under the study of modern mathematics, have developed remarkable facilities to design and control such systems in musical performance. This accomplishment only points to the capacity of the human sensory-motor system to perceive patterns of trajectories and to act to counterbalance them, an ability which often functions at intuitive rather than analytic levels of thought.

IV. Conclusion: Listening and Double Description

While this article focuses on Dunn’s site-specific performance works, language pieces, and nonlinear circuits, a significant amount of Dunn’s work engages the concept of listening. Works such as Purposeful Listening in Complex States of Time (1998), Why Do Whales and Children Sing (1999), and Listening to What I Cannot Hear (2008) address questions of why and how to listen, as well as the role technology can play. Dunn’s interest in listening practices is also related to his work as a field recordist and recording engineer. Throughout his career, Dunn worked professionally as a sound engineer for studio and location recordings and as a field recordist and sound designer for museums, zoos, and films.60 As is likely evident, recorded sound in one form or another is a crucial element in most of Dunn’s compositions. His fascination with recording technology is clear in his inclusion of specific recording instructions, such as the type and placement of microphones—decisions which are compositional as much as they are technical—as well as the use of field recordings and intricate recording and playback systems.

Dunn typically employs technology to access sounds otherwise unavailable to human auditory perception. He also sees technology and listening practices as a partial solution to large-scale global problems. In the face of global climate change and ecological disaster, Dunn now recognizes that “one of the best uses of my time, as a composer, is to simply listen to some of nature’s changing messages and pass them along to others.”61 For Dunn, environmental sounds provide access to a larger system of mind, and that it is crucial for humans to recognize their place in these interconnected systems. As such, he is interested in all vibratory phenomena—whether underwater, underground, within the surface of trees, above or below the human hearing range. Dunn developed a practice of designing custom transducers to capture these sounds that are not otherwise accessible by conventional recording devices or human hearing. For instance, Listening to What I Cannot Hear (2008) is composed entirely of ultrasonic recordings transposed into the human hearing range.

In 2006, Dunn released The Sound of Light In Trees, a project in response to bark beetle infestation of North American pine forests. The Sound of Light in Trees is a recording of the interior of an infested tree, made using custom transducers fashioned from cheap meat thermometers that Dunn placed between the outer bark and inner xylem of the tree. The resulting soundscape is a dense and complex web of communication, not just amongst the bark beetles but between the bark beetles and their environment, the tree. At the time, existing research on bark beetle communication focused on chemical systems. Together with insect ecologist Richard Hofstetter and his assistant Reagan McGuire, Dunn developed a strategy to use sound to manage bark beetle infestations through a combination of random playback of bark beetle sounds together with and modulated by chaotic sound synthesis—using the circuitry designed for Thresholds and Fragile States. The bark beetles are exposed to a stream of signals to which they cannot habituate. In the resulting panic, their instincts go haywire, and they die either by cannibalism or suicide.62

The Need For A Double Descripton

While Dunn’s work contains many seemingly divergent strands and trajectories, central is the concept of mind and how to strengthen one’s sense of mind through sound. In recent writings, Dunn frames his body of work as emanating from two fundamental questions

(1) What does music contribute to our understanding of the question of mind? How is it structured and where is its locus?

(2) What is accomplished by strengthening our aural sense within a culture that is visually dominant in that most of the metaphors that we use to construct and describe our experience of the world are based upon the sense of sight? What is gained or lost by a shift towards an aural perception of the world?63

For Dunn, the purpose of music lies at this nexus of mind and aural senses. Music allows humans to experience and find their place within a larger system of mind that is their environment. In a way, the underlying conception of mind lives at some triangulation between interaction, language, magic, ecology, complexity, and art. Each metaphor provided Dunn with language to express his compositional ideas, and, in turn, each metaphor also shaped his understanding of the implications of his work. Dunn’s use of shifting metaphors of mind are also evidence of his willingness to embrace alternate explanations of the world.

While reflecting on his work and role as a composer, Dunn commonly refers to principle of the double description, epitomized by Bateson’s dictum: “The richest knowledge of the tree includes both myth and botany.”64 For Dunn, the necessity of a double description requires learning to integrate multiple domains of explanation—often art and science—or, as Dunn states: “Walk[ing] the middle path of double description.”65 In 2014, while discussing his use of sound to combat bark beetle infestations, Dunn said: “I’d like to demonstrate the efficacy of sound as an alternative to chemical pesticides not just because the world needs it, but because artists need it.”66 Dunn hopes to show the world that by walking the middle path we can solve the most dire problems facing humanity today.

1Personal conversation with David Dunn. Throughout this article many quotes are taken from stories and statements made by Dunn while the authors worked as his students at the University of California, Santa Cruz from 2014–2018.

2Dunn learned to play all of Partch’s instruments, however the adapted viola was his specialty. According to Dunn, it was the most difficult to play.

3David Dunn, “Wilderness as a Reentrant Form: Thoughts on the Future of Electronic Art and Nature,” Leonardo 21:4 (1988): 377.

4Personal conversation with David Dunn, January 30, 2018.

5David Dunn, “Cybernetics, Sound Art, and the Sacred,” (2004), 9. “Structural coupling” is a term devised by biologist Francisco Varela and Humberto Maturana. A more thorough discussion of this concept is provided in the section titled, “Autonomy, Chaos, and Models of Mind.”

6David Dunn, liner notes, Music, Language and Environment: Environmental Sound Works by David Dunn 1973–1985, (1996), CD.

7David Dunn, “Nature, Sound Art, and the Sacred,” in The Book of Music and Nature, edited by David Rothenberg and Martha Ulvaeus, (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 101.

8David Dunn, liner notes, Music, Language and Environment.

9David Dunn, Skydrift, (Lingua Press: La Jolla, 1979), 4.

10Personal conversation with David Dunn, January 30, 2018.

11David Dunn, Skydrift, 4.

12Ibid.

13Dunn and Gaburo were previously friends, at this time they were deeply involved in a 1979 performance of Partch’s Bewitched (1955). In addition, Dunn spent approximately 20 hours a week with Gaburo to learn about his approach to language in compositions. The two remained close until Gaburo’s death in 1993. Personal conversation with David Dunn, January 30, 2018.

14This demonstrates Gaburo’s impact on Dunn, however he also cites his father’s work as a draftsman as a significant influence on his notation.

15David Dunn and Michael R. Lampert, “Environment, Consciousness, and Magic,” 101; and David Dunn, Madrigal: The Language of the Environment is Encoded in the Patterns of its Living Systems, 1980.

16David Dunn and Michael R. Lampert, “Environment, Consciousness, and Magic,” 100.

17David Dunn, “Speculations: On the Evolutionary Continuity of Music and Animal Communication Behavior,” Perspectives of New Music 22:1/2 (Autumn, 1983–Summer, 1984): 87.

18David Dunn, “Mappings and Entrainments,” (1984), 1.

19David Dunn, Entrainments 1: Enfolded Traces of Environment’s Memory Revealed in Holonomic Space, (1984), 1.

20Ibid.

21David Dunn, Entrainments 2: Geomantic Mappings of Eco-Systemic Resonance, (1985), 1.

22Ibid.

23David Dunn, “Nature, Sound Art, and the Sacred,” 102.

24Ibid., 103.

25David Dunn and Michael R. Lambert. “Environment, Consciousness, and Magic,” 105: Dunn calls for a redefinition of our “relationship to the environment that is life-enhancing.”; David Dunn, “Nature, Sound Art, and the Sacred,” 97.

26David Dunn, Michael R. Lampert, “Environment, Consciousness, and Magic,” 102.

27David Dunn to Kenneth Gaburo, 26 June 1986, Series 1, Box 2, Folder 31, Kenneth Gaburo Papers 1936, 1945–1993. The Sousa Archives and Center for American Music. University of Illinois Libraries.

28David Dunn, Michael R. Lampert, “Environment, Consciousness, and Magic,” 102.

29He also advocated for “individual science,” claiming: “An individual Gnosis is threatening to any reigning hierarchy of belief.” David Dunn to Kenneth Gaburo, 26 June 1986, Series 1, Box 2, Folder 31, Kenneth Gaburo Papers 1936, 1945–1993. The Sousa Archives and Center for American Music. University of Illinois Libraries.

30David Dunn and Michael R. Lampert, “Environment, Consciousness, and Magic: An Interview with David Dunn,” Perspectives of New Music 27:1 (Winter 1989): 104.

31David Dunn, Skydrift, 4.

32David Dunn, Entrainment 1, (1984), 1.

33Dunn quotes Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind, in “Cybernetics, Sound Art and the Sacred,” (2004), 3.

34Ibid.,14.

35David Dunn, “Cybernetics, Sound Art and the Sacred,” (2004), 15; in the same article he restates this idea: “Music is the same as mind, a distributed ecology of communal signification where meaning arises from the conditions of mutual conspiracy.” 7.

36Personal conversation with David Dunn, University of California, Santa Cruz, 2014–2018.

37Francisco Varela, Principles of Biological Autonomy, (New York: Elsevier, 1979), 3.

38David Dunn, “Listening to the Soundscape,” (2012), 12.

39David Dunn, Simulation 1: (Sonic Mirror), (1986), 1.

40At the time commercial options were not available, and Dunn built his system from a 6502 microprocessor, a chip that was instrumental in the growth of home personal computers in the 1980s. Dunn programmed routines for basic audio manipulations, including forward and reverse playback, octave division, transposition, delay, looping, vibrato, and sample playback. The score includes wire wrap diagrams and hexadecimal code routines, reflecting Dunn’s desire in and search for an adequate means of documentation.

41David Dunn, Simulation 1: (Sonic Mirror), (1986), 1.

42Ibid.

43Ibid.

44Such as weather patterns or water dripping from a leaky faucet. Edward Lorenz, one of the first scientists to effectively employ chaos theory in the 1960s, dealt with the problem of weather prediction; Robert Shaw’s 1984 PhD thesis at the University of California, Santa Cruz identified predictable patterns of motion in the behavior of a dripping faucet.

45David Dunn, Pleroma SERIES, (1999–2000).

46David Dunn, “Thresholds and Fragile States,” Moebius 1 (2012): 1; italics, author's emphasis

47Each circuit is a unit of three sine wave oscillators—one of the simplest means of achieving chaotic behavior from traditional electronic music elements is by cross-coupling sine wave oscillators in frequency modulation, each oscillator’s output is connected to the other’s frequency control. Individually, each circuit exhibits chaotic behavior. The chaotic circuits in Pleroma are implemented digitally using the software Reaktor.

48David Dunn, Pleroma SERIES, (1999–2000).

49Ibid.

50Ibid.

51Ibid.

52David Dunn, Autonomous Systems: Red Rocks, (2003), 1.

53David Dunn, lecture, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, January 29, 2018.

54Dunn’s oscillators are derived from a circuit published in a 2000 physics article documenting a class of recently discovered simple chaotic circuits: Julian Sprott, “Simple Chaotic Systems and Circuits,” American Journal of Physics 68:8 (2000): 758–764.

55David Dunn, liner notes, Autonomous and Dynamical Systems, (2007), CD.

56David Dunn, “Thresholds and Fragile States,” (2012), 2.

57Ibid.

58David Dunn, “Thresholds and Fragile States,” (2012), 11.

59David Dunn to Kenneth Gaburo, 26 June 1986.

60While Directory of Electronic Music Studios at San Diego State University, Dunn had the opportunity to assist influential recording engineer Wes Dooley, whom the university hired to record concerts. Dooley introduced Dunn to novel spatial recording techniques, such as mid-side and binaural, which Dunn uses in his field recording work to record and reproduce acoustic spaces and environments.

61David Dunn, “A Philosophical Report from Work-in-Progress,” 1.

62David Dunn and Michael R. Lambert, “Environment, Consciousness, and Magic: An Interview with David Dunn,” Perspectives of New Music 27:1 (Winter 1989): 94–105.

63David Dunn, “Cybernetics, Sound Art, and the Sacred,” (2004), 3.

64Dunn quoting Mary Catherine Bateson in “Listening to the Soundscape and the Necessity of Double Description,” Moebius 1 (2012): 2. Original quote from: Gregory Bateson and Mary Catherine Bateson, Angels Fear, Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred, (New York: MacMillan, 1987).

65David Dunn, “Listening to the Soundscape,” (2012), 19.

66Personal conversation with David Dunn, November 19, 2014

Works cited

Dunn, David and Michael R. Lambert. “Environment, Consciousness, and Magic: An Interview with David Dunn.” Perspectives of New Music 27:1 (Winter 1989): 94–105.

Dunn, David and James P. Crutchfield. “Entomogenic Climate Change: Insect Bioacoustics and Future Forest Ecology.” Leonardo 42:3 (June 2009): 239–244.

David Dunn to Kenneth Gaburo, 26 June 1986, Series 1, Box 2, Folder 31, Kenneth Gaburo Papers 1936, 1945–1993. The Sousa Archives and Center for American Music. University of Illinois Libraries.

Dunn, David. “Speculations: On the Evolutionary Continuity of Music and Animal Communication Behavior.” Perspectives of New Music 22:1/2 (Autumn, 1983 - Summer, 1984): 87–102.

_______. “Mappings and Entrainments.” 1984. Unpublished.

_______. “Music, Language, and Environment.” 1984. Unpublished.

_______. “Wilderness as a Reentrant Form: Thoughts on the Future of Electronic Art and Nature.” Leonardo 21:4 (1988): 377–382).

_______. Liner Notes. Music, Language and Environment: Environmental Sound Works by David Dunn, 1973–1985. Innova Recordings. CD, 1996.

_______. “Nature, Sound Art, and the Sacred.” In The Book of Music and Nature. Edited by David Rothenberg and Martha Ulvaeus. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

_______. “Santa Fe Institute Public Lecture.” Lecture, Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe Institute Public Lecture Series, Santa Fe, NM, August 15, 2001.

_______. Liner Notes. Four Electroacoustic Compositions. Pogus Productions. CD, 2002.

_______. “Cybernetics, Sound Art, and the Sacred.” 2004. Unpublished.

_______. Liner Notes. The Sound of Light in Trees. Earth Ear. CD, 2006.

_______. Liner Notes. Autonomous and Dynamical Systems. New World Records. CD, 2007.

_______. “Listening to the Soundscape and the Necessity of Double Description.” Moebius 1 (2012): online publication.

_______. “Thresholds and Fragile States.” Moebius 1 (2012): online publication.

_______. “The Limits To Listening.” Keynote address, The Conversation: Reciprocal Relations in Sonic Ecology, Surrey Art Gallery, Vancouver, Canada, November, 2014.

_______. “A Philosophical Report from Work-in-Progress.” In Environmental Sound Artists: In Their Own Words. Edited by Frederick Bianchi and V.J. Manzo. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Davis, D. Edward. “The Map and the Territory: Documenting David Dunn’s Sky Drift.” Organised Sound 22:1(2017): 122–129.

Ingram, David. “‘A Balance that you can Hear’: Deep Ecology, ‘Serious Listening’ and the Soundscape Recordings of David Dunn.” European Journal of American Culture 25:2 (2006): 123–138.

Gottschalk, Jennie. Experimental Music Since 1970. New York: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Sprott, Julian. “Simple Chaotic Systems and Circuits.” American Journal of Physics 68:8 (2000): 758–764.

Varela, Francisco. Principles of Biological Autonomy. New York: Elsevier, 1979.

Scores

Dunn, David. Nexus 1. 1973.

_______. Oracles: Ten Environmental Stimulus Compositions. 1975.

_______. Skydrift. La Jolla: Lingua Press, 1979.

_______. (espial): For Solo Violin. 1979.

_______. Madrigal: The Language of the Environment is Encoded in the Patterns of its Living Systems. 1980.

_______. Ring of Bones. 1981.

_______. Entrainments 1: Enfolded Traces of Environment’s Memory Revealed in Holonomic Space. 1984.

_______. Entrainments 2:Geomantic Mappings of Eco-Systemic Resonance, 1985.

_______. Simulation 1: Sonic Mirror, 1986.

_______. Wildflowers, 1994.

_______. Pleroma SERIES, 2000.

_______. Autonomous Systems: Red Rocks, 2003.

Dunn, David, and Chris Mann. Position as Argument. 1982.