Tuning is the cornerstone of a contemplative sonic artistic practice. My thoughts have been drawn to considering how my conception of tuning evolved over time and how ratios became the driving force in my work.

It is through the sustained practice of tuning that I came to understand time and its inextricable relationship to ratio. Reflecting on the example set by La Monte Young, tuning is already firmly established as a function of time. Therefore by listening, hearing, and truly experiencing a ratio and its tuning we can endeavor to develop an understanding of the feeling of time and perceive it through an intense focus on tuning, or rather, ratio.

I began studies with Young and Zazeela in 2003. At that time the idea of pure non-equal tuning was entirely novel. Considering an interval as a ratio was only something I had read about. Over time I learned tuning first-hand in the Kirana tradition and developed an appreciation for a devoted approach to ratios and refinement.

In a remarkable confluence of events, I came to La Monte and Marian when my work needed it most. In the subsequent years events would align such that time and place would allow for the creation of my own integrated numerical cosmology: The Four Pillars, a tuning system built from pure exponential harmonics of a single fundamental frequency.

Of course, Just Intonation itself is a very open tuning concept. You can recreate sounds from an older time or explore ratios more abstract than anyone has ever heard. This tuning practice – clarifying it, focusing it – we come to its core in time: exploring the energy of pure ratio, expressed as tuning, heard in the real world.

The fundamental tenets of Just Intonation allow us over time to expand our focus from tuning a single ratio perfectly to experiencing a rich web of relationships. The way we choose to use this system of tuning (as with any system) is where art happens. Ratios are the building blocks, and their combinations become transcendent when a confluence of intervals creates a new otherworldy sonic situation.

Moving beyond the standard or accepted ratios (threes and fives, say) a tuning can, with time and attention, take on wilder numbers–La Monte's sevens. I quite like elevens too. Larger prime numbers can align to highlight certain intervals (Prime Time) and can even be used in combination to create new tones that reinforce the tuning that is already present.

These ratio relationships, if time is taken to cultivate them, become self-reflective all-encompassing universes built from tuning a small set of pitches. These can feel familiar through the harmonic series – it's all around us, resonating out its tuning from every sound, complex or simple. Overtones follow these numerical rules (most of the time), spell out ratios across the tuning spectrum, getting smaller and smaller the higher up we go.

Knowing this we can embark on a time-honored ancient tradition: tuning a single ratio to the overtone series, say with a tambura or sine wave drone, allowing freedom through reference. The confluence of stasis and freedom brings rise to new ratio possibilities. Knowing the point of reference, we can travel far.

This tuning practice takes time to develop; hearing the beats slow and eventually stop, feeling the ratio lock into place.

Working with tuning in this way feels transcendent.

Time stops when the whole composite waveform comes into sharp focus. The way the interval aligns becomes the composite waveform expressed in space every time the interval is heard. Within a system of Just Intonation these tuning shapes become periodic. Using pure ratios it becomes possible, within a lifetime, to comprehend these intervallic relationships precisely.

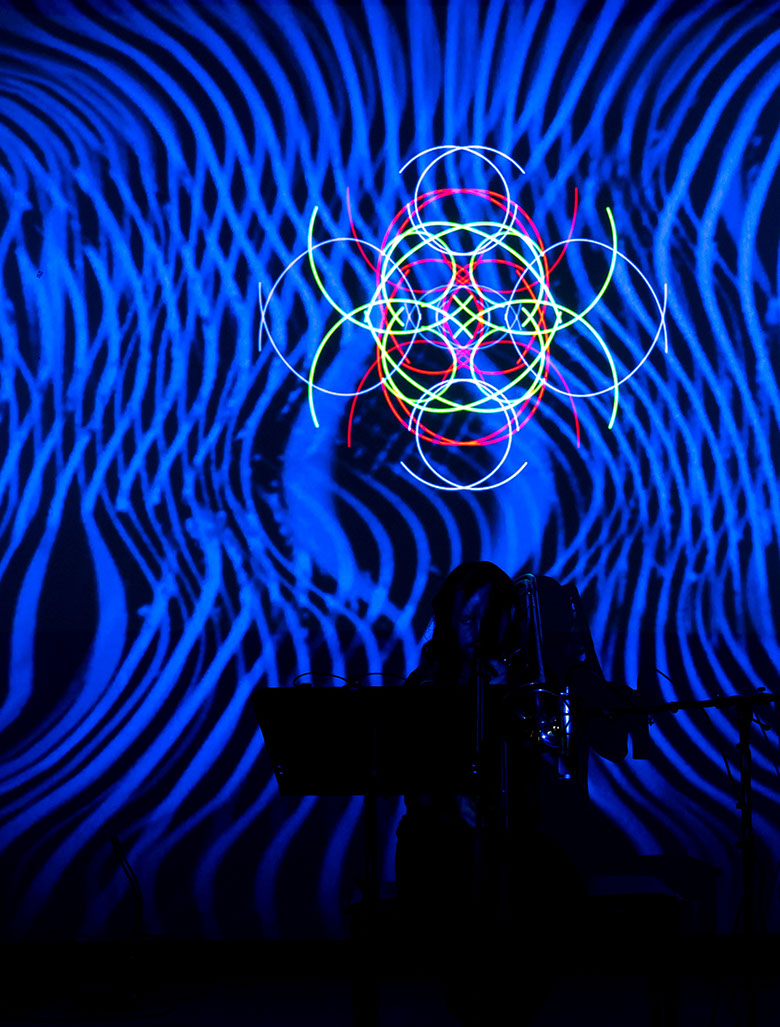

While developing tunings system of my own I became interested in the way that ratios, content, and time could come together as a tuning of the entire performance situation.

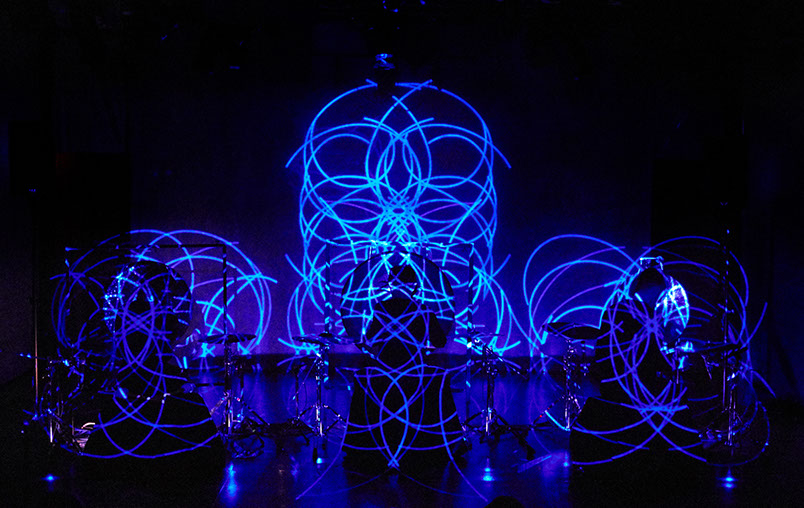

Durations within a work became tied to these same numbers. How many harmonics available for tuning became tied to these same numbers. The visual environment of the performance became tied to these same numbers. I observed confluences in these ratio relationships across mediums.

The impetus of the composition became inextricably linked to the expression of this total tuning system with time as the primary concern. A ratio in sound translated elegantly to a similar relationship in duration. With tuning of the pitches decided, the time of the composition becomes the next stage for ratio exploration. A work where the tuning is built exclusively from nines readily fills the time of 81 minutes.

With this sort of interrelated ecosystem, compositional concerns align to create powerful resonances often imperceptible to the listener regardless of time.

Expanding now my use of Just Intonation beyond tuning in the sonic realm the ratios can be explored in their purely physical manifestations. Time itself can become the definitive tuning experience. Considering that sound is itself physical, jumping to objecthood means ratio can be delineated abstractly and time can reveal tuning as a concrete conception. The direct relationship of line, space, color, word, tone, vibration, or light outline ratio in a confluence of medium and intention.

I have long considered my work as an ongoing refinement of a specific set of relationships. Tuning of a harmonic started as the foundation of this practice, as learned from La Monte, but now I find myself considering tuning as a function of life. Time becomes a ratio of experience, a fluid medium equally subject to the principles of tuning.

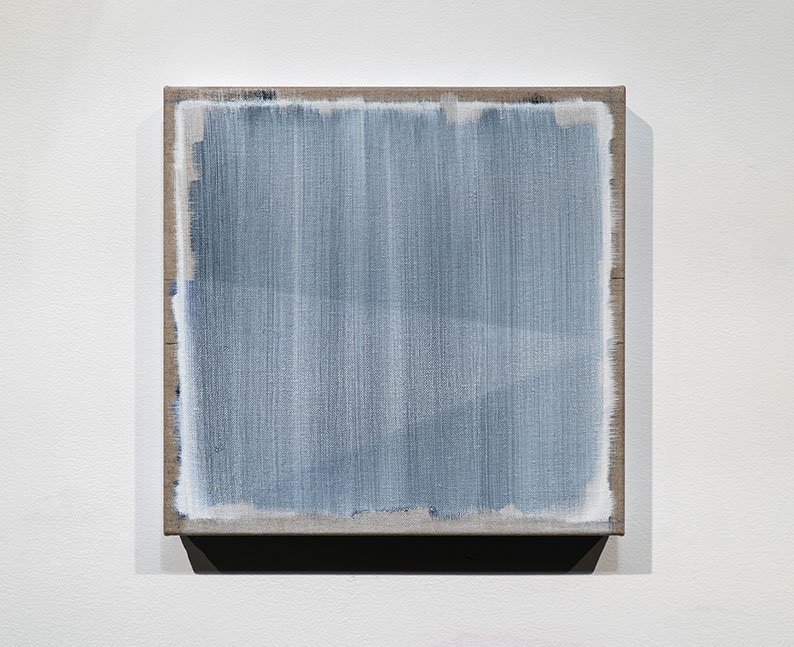

Shape and form (compositional form or physical), clock time (or astronomical); these concerns of ratio translate readily to the physical tuning of objects and environment.

An art of light and space and time built wholly on the foundational physics of sound.

Aligned with this new paradigm I have a blueprint for a way to make work.

Time is my primary compositional concern. Tuning has been decided upon, and ratio is a given within this cosmology. The decisions become quite simple. Time works within tuning to create form. Dimensions and pigments reference the numbers of my ratio systems. The lines in the video work enjoy confluence of shape, duration, and speed, all referencing these numbers.

What I'm after is an artistic situation where ratio, color, duration, tuning, pitch, and time all exist in the same self-logical environment. They are, and simultaneously aren't, part of one piece, existing as conceptually pure ratios and embodying time and space in the moment: fluid but logical from iteration to iteration. If I'm tuning a piano or setting a wedge in paint, harmonic structure is the backbone whether audible or not.

Having this foundational tuning experience outside traditional western methods has encouraged my tendencies toward extreme time. Allowing the ratio to speak for itself through tuning, and asking unmediated focus on that experience, is an act that takes a long time. I had to learn to align myself to these interests and understand that this world was one of gradual change.

Degrees of difference (time-based or not).

Tuning as a manifestation of concept. Ratio as definitive form.

Working in this way presents an unusual set of challenges. Exploring confluence across mediums means the work can rarely exist as a single ratio unimpeded. The entire situation must conform to the tuning so that time can become malleable. The entire experience is “in tune” and therefore the audience understands ratio, and yes tuning, through a new lens. Each time these ideas are returned to, the audience can access memory of the past and tuning can highlight ratio in a way that uses time to its advantage. Hearing or seeing an interval durationally means that tuning becomes a common language.

One may not perceive ratio, duration, color, or time as conforming to the rules of the tuning, but the imperceptible allows discovery. The outward similarity of the experience (minimalism) encourages a harmonic experience that becomes self-reflective.

Redefining tuning as an all-encompassing activity means it's not necessary for the experiencer to know the structure involved. Spending time with this aligned work is all that's required. Your own experience is paramount. You may notice a new subtle detail. You may find confluence while others’ attention is elsewhere.

Ratios become readily apparent when your perception is sufficiently, slowly, opened.

Your own experience is tuned to your time in this world.

My experience, your experience. This ratio, that relationship. We all have individual predispositions, so tuning this way becomes about allowing time for discovery, embracing the individual experience and understanding that, for each ratio within the tuning, a high level of intention must be given time to flourish. Knowing this, we ask the same of our audience.

Tuning activates the ratio of experience. Perception activates the totality of shared time.

Just Intonation is a lens through which a tuning of this magnitude can be cultivated beyond the ratios, beyond the notes, beyond the time of it. This practice of tuning our situation proves relevant throughout our existence; a new methodology to engage our perception.

Ratio mediates the timed experience of tuning as totality. We embark on this practice as a shared sublime experience. Our aim is a pure and completely transformative harmony.