Lee Hyla never talked to me about wanting to write an opera. Not that I expected him to. I don’t think we talked much about any operas, whether by Mozart, Britten, or Philip Glass. From our student days at New England Conservatory (NEC) in 1973 to ’74, Lee and I had plenty of other things to talk about, with our shared backgrounds as jazz and rock pianists. We had both moved on to the concert-music versions of those bands: financially marginal but musically lively new music ensembles such as Dinosaur Annex, which I co-founded and directed in Boston. Lee was a member of the Dinosaur Annex board of directors before moving onto the advisory board, as I eventually did myself. After he and his wife, Kate Desjardins, moved to Chicago, he stayed involved with Dinosaur Annex by recommending his best Northwestern students for our Young Composers Festival.

Our decades-long conversation was focused on this modern chamber music, in which Lee, by the 1980s, had emerged as perhaps the most influential composer of our generation. It seemed a waste of time for either of us to pay too much attention to the larger and more highly publicized areas of classical music, which marginalized living composers while lavishing attention and high fees on each generation of young performers to reward the rediscovery of the masterpieces of their great-grandparents.

It’s not that Lee didn’t care about the orchestra. He taught orchestration at NEC, and his powerful orchestral CD Trans, played by the Boston Modern Orchestra Project under conductor Gil Rose, gives an idea of the treasures yet to be discovered by the larger orchestra world. Though Lee lived for several years each in Boston, New York, and Chicago, the flagship orchestras of those cities, all of whom pay lip service to the music of our time, never played a note of this master composer in their midst.

If the orchestra world wasn’t where much of the new-music action was, opera was even less so. I remember feeling a little sheepish when I confessed to Lee, in 1999, that I needed to miss some major new-music event in Boston in order to see soprano Renée Fleming in Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah at the Met, where Renée and I discussed a commission for some songs.1 I figured Lee would disdain my interest in that sort of singer or the operas she sang. So, it was a little surprising to discover that Lee had himself been planning to write an opera based on the painter Caravaggio. What a great idea. Lee’s combination of wild musical invention, expressive extremes, and highly controlled craft would have provided some real excitement in the world of modern opera.

It’s also a crazy idea, I suppose: I can hear the opera producers and singers asking, “But where are the tunes? The repetitions? And how can the performers learn such difficult music?” I also hear the mantras of opera company directors regarding new works: “How are we to market this to our community? Why are we telling this story now?” All these fearful questions could be equally asked in order to avoid the artistic and marketing challenges of the modernist operas of Henze, Ligeti, or Harrison Birtwistle, let alone the more recent modernist works by George Benjamin, Kaija Saariaho, Olga Neuwirth, Thomas Adès, Salvatore Sciarrino, and others currently receiving high-profile European—and, occasionally, critically acclaimed American—performances. The now-accepted operas of Britten, Janáček, Strauss, and Shostakovich faced similar objections half a century ago from timid American companies, including the Met. A smart, American version of modernist opera such as what Lee dreamed of might have had a chance of creating genuine operatic excitement, if a company were brave enough to try it.

What might this Lee Hyla Caravaggio opera have been like? I spoke to bass-baritone David Salsbery Fry, who met Lee at Tanglewood in 2011 ; Lee told David that he had been thinking about the piece for twenty years and David would be ideal in the title role. Mezzo-soprano Mary Nessinger, for whom Lee wrote much of his vocal music, says that he planned to include her in the eventual cast and to incorporate the extremes of her range and expression, what she calls the “schizophrenic” aspects of his writing in which she excels. As in Lee’s 1998 Lives of the Saints, Mary was to take on multiple roles, not only from the painter’s life but from his paintings, including the role of Mary Magdalene. Lee discussed the project with Opera Boston, whose artistic director Gil Rose had already conducted three CDs of Lee’s work. There seems to be no surviving libretto for the opera ; apparently Lee considered the first-rate fiction writer Francine Prose, but Kate believes that Prose was never approached.

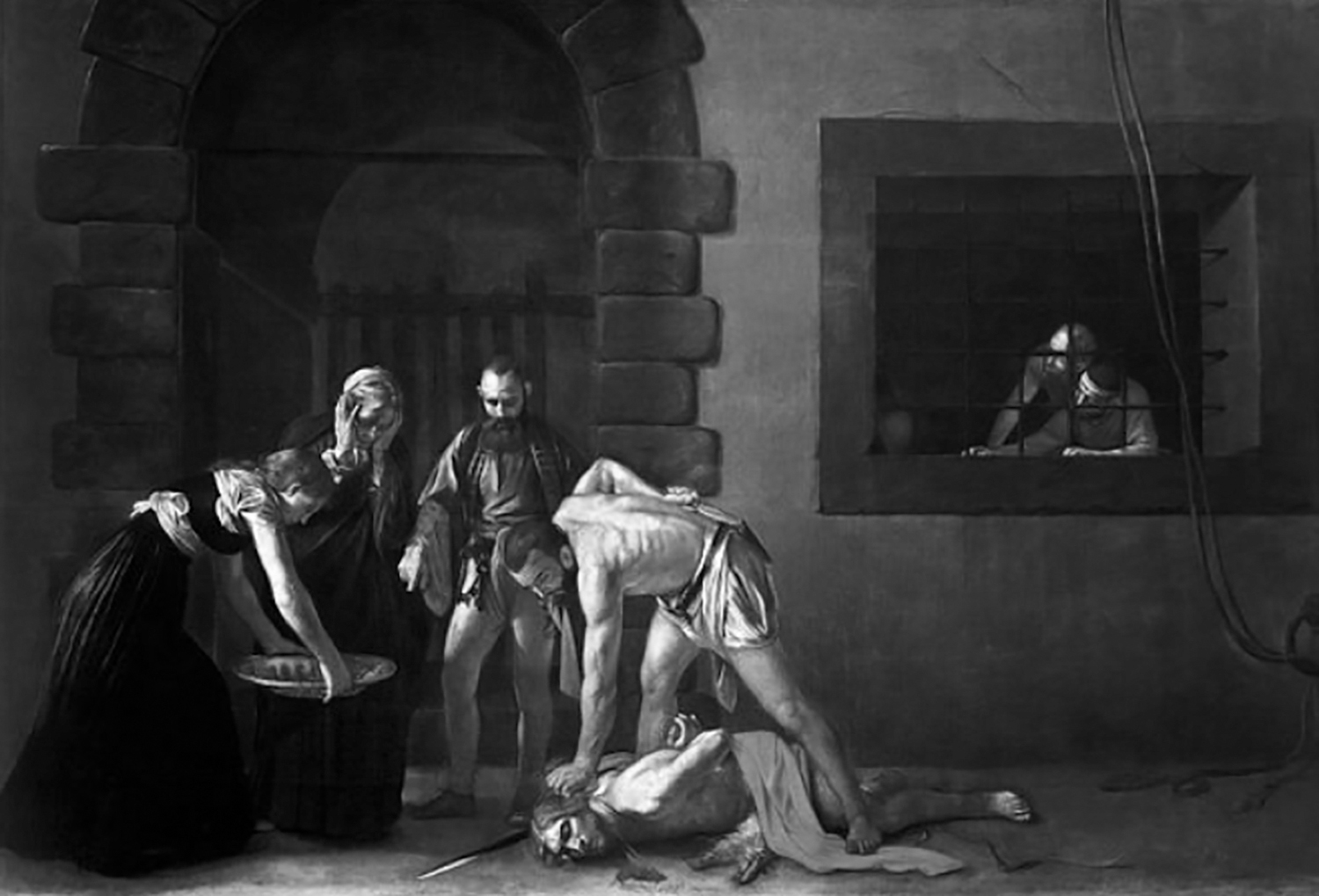

Kate shared a number of other insights as well, including a few of Lee’s handwritten notes. “Lee was looking for a reconsideration of Caravaggio as an artist trying to make his own way, a victim of larger forces rather than merely a murderer and homosexual. How can you be yourself? It’s a very American theme.” Caravaggio’s story is certainly an “operatic” one ; Kate explained that “all through the opera, Caravaggio is on the run.” But Lee’s conception of the opera was less chronological than visual, based on Caravaggio’s paintings. Lee and Kate (herself a well-known painter) imagined projections of the paintings, brought to operatic life as tableaux vivants, which would in turn connect to events from Caravaggio’s life. Lee saw the paintings as nodal points in the opera, often connecting the life events with the locations of the paintings. A particularly potent image for Lee was that of Caravaggio’s excommunication from the Knights of Malta, which occurred in absentia, in front of Caravaggio’s own great altar-piece painting of The Beheading of St. John the Baptist.

Other paintings Lee planned to incorporate, with their locations to anchor them to the opera’s narrative, included the Adoration of the Shepherds, painted in Messina, The Burial of St. Lucy (patron saint of painters) in Sicily, The Flagellation of Christ in Naples, The Death of the Virgin in Rome, and The Denial of Saint Peter, which was finished in Naples. Lee’s fascination with the more extravagant expressions of Italian Catholicism no doubt stem from his Polish-American roots, especially his Catholic upbringing and altar-boy youth. Kate quotes Lee: “I was going to be a priest—then I discovered girls and rock and roll.” A piquant note in Lee’s hand mentions West Side Story as a model—Kate says that Lee loved this show and connected it to his notion of Caravaggio as a martyr.

Lee left no musical sketches for his Caravaggio opera; Kate reports that he was listening intently to Bach’s St. Matthew and St. John passions as inspiration.2 We can, however, conjecture how Lee might have approached the opera based on his existing music, especially the 1998 Lives of the Saints: Lee’s first piece for singing voice, and one of his most powerful and original works. Those of us who had avidly followed Lee’s music from its early years were accustomed to hearing frantic chattering, angry rants, brief moments of ecstasy, mysterious murmurings, and funky riffs, all presented without transition and often with deadpan humor. None of these characteristics of Lee’s music seemed to have much to do with vocal music by classically trained singers, so when Lives of the Saints emerged, it was something of a shock to find all these instrumental elements still present, uncannily mirrored in both the vocal line and in the texts he selected.

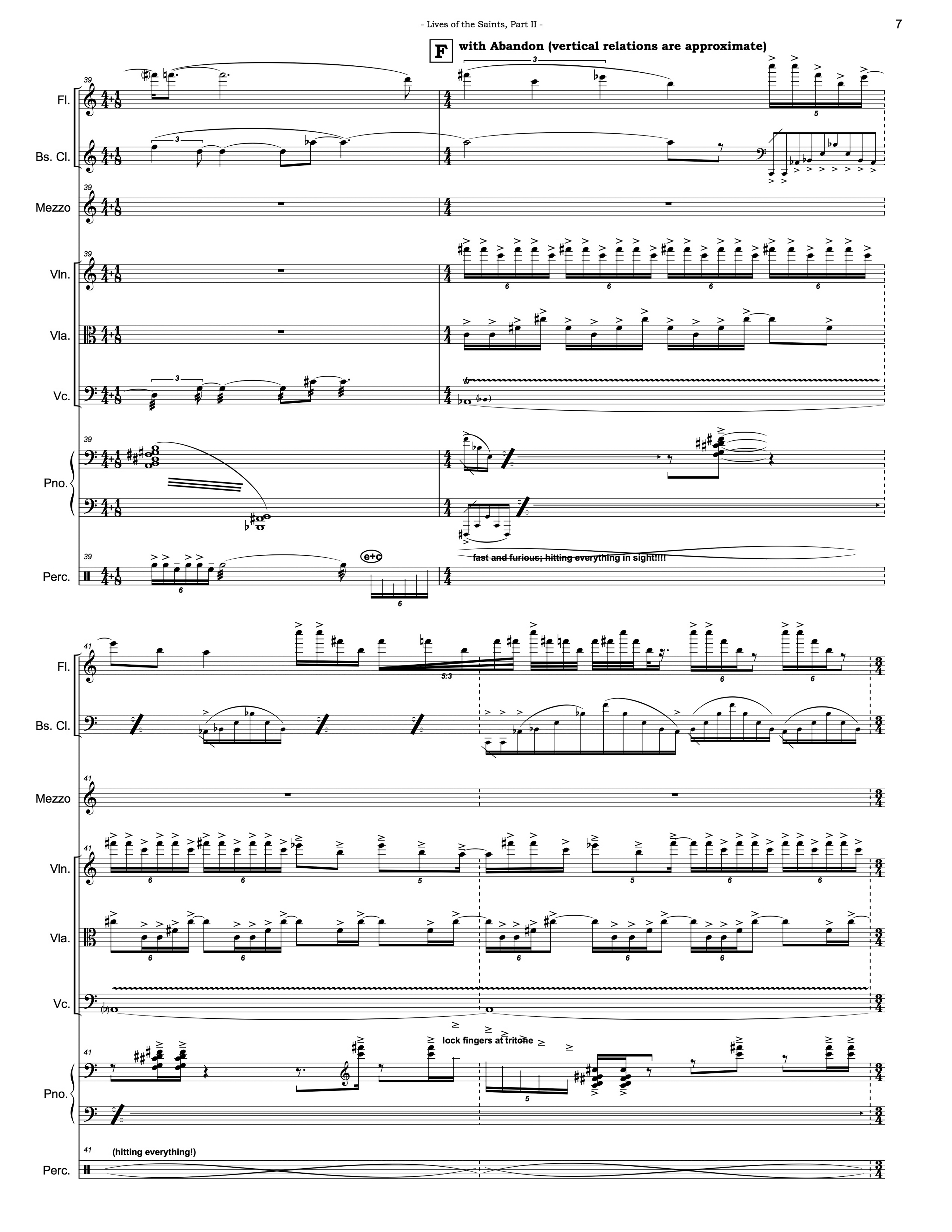

A non-linear monodrama in which the solo mezzo-soprano takes on multiple roles, Lives is probably the work closest to what Lee intended for his Caravaggio opera. Lee’s liner note to the BMOP CD describes Lives as “more a set of character studies than a meditation on saintliness itself.” Martin Brody’s insightful liner note describes “recitative/aria pairings projected on a large scale.” Brody’s description is apt, if one expands one’s definition of recitative to accommodate Lee’s precisely notated parlando, intricately linked to the instrumental counterpoint and heterophony. The effect in Lives of the Saints is less like the snappy dialogue of Mozartean recitative than like the rapid intonation of liturgical chant. In the opening passage from Lee’s setting of Canto III of Dante’s Paradiso, Dante sings in English but Beatrice responds in Italian, a vivid, truly operatic moment that is marked by a register shift from B-flat down to C-sharp. The work’s musical climax is the torture of St. Lawrence, which is depicted as orchestral madness resembling free jazz, abruptly stopping to allow the saint to speak (not sing) the famous line, “Turn me over. I’m done on that side.” In both its musical language and in its dark, deadpan humor, this is Lee Hyla as the blackest of black comics, a trait which would surely have found a place in the planned Caravaggio opera.

Mary Nessinger remembers Lee singing his vocal lines to her. She comments, “It’s strange that it took Lee so long to come around to writing vocal music, because his music emerged so naturally from his own speaking and singing voice. He loved to sing in extreme registers and tempi.” She also commented on Lee’s fondness for abrupt tempo shifts and recalled times when he registered strong objections to a performer softening one of these shifts into something more conventionally transitional. These abrupt moments relate to Lee’s background in rock, but they are also highly stage-worthy—Puccini, Mozart, and Berg would all recognize this sort of coup de théâtre as a powerful tool of the musical dramatist.

The musical climax of Lives of the Saints—the torture of St. Lawrence. The “orchestral madness” comes to an abrupt halt, allowing the “saint to speak (not sing) the famous line, ‘Turn me over, I’m done on that side.’ ”

Musical extremes of all kinds have always been a hallmark of opera, as evidenced in the colloquial use of the word “operatic” to mean “violently emotional.” In this sense, Lee’s music always tended toward the operatic, seldom lingering in a pleasant middle range of tempo or dynamics. Lee tolerated but had little interest in music occupying the middle range, whether the American mid-century neo-classicists or the many minimalists whose lightly syncopated motor rhythms on pleasant pop chords were so common in the late years of the last century. I once heard Lee dismiss that sound as “happy talk.” For this reason, I’ve always considered Lee to be part of the expressionist tradition of Schoenberg, Carter, and Wolpe, combined with the American jazz expressionist tradition of Cecil Taylor or Anthony Braxton.

Although Lives of the Saints was the first Hyla work for singing voice, Lee had written a major piece with spoken text in 1993. Howl was premiered and recorded by the Kronos Quartet, with the voice of Allen Ginsburg reading his most famous poem. The Hyla alternations of manic, jagged gestures, musical snarls, riffs from some avant-garde rock band, and passages of haunted stillness connect to similar elements in the Ginsburg and prefigure the ways Lee would eventually approach sung vocal music. By combining speech and instrumental music in Howl, Lee sidesteps a central problem for modern American composers : classically trained singers don’t usually sing American English in a way that speaks directly to an audience, or is even comprehensible. This is the biggest obstacle to opera for any American composer with a sense of the vernacular : opera singers treat English as something very formal, often sounding British or self-consciously upper class. When they speak they are obviously American, but they sing like foreigners. It seems likely that their teachers propose Italian as the natural language for singing, and accordingly teach English diction as a special problem to be translated from the Italian. Whatever the reason, American composers wanting to work with text have had to find ways around the problem. Steve Reich established the radical solution adapted by many composers, insisting that vocalists in his works use microphones, often speaking rather than singing. In Reich’s works with recorded speech, such as the early Come Out and the masterful The Cave, the words and intonations of the spoken language are first recorded, then mirrored in the instrumental parts. Scott Johnson’s John Somebody is a brilliant extension of this delightful, if limited, technique. Lee Hyla’s Howl is a landmark work in this tradition.3

The early Philip Glass vocal works are sung but avoid the text problem both by using non-operatic singers and by avoiding text itself, giving the miked singers syllables or numbers (Einstein on the Beach) or Sanskrit (Satyagraha). Erin Gee takes an updated non-verbal approach in her enchanting Mouthpieces series. But most composers eventually chafe at these limitations and look for ways for sung text to convey meaning. If the singer is not the composer, and especially if trained opera singers are featured, this creates a tricky problem both for melodic structure and for rhythmic notation. Many neo-Romantic composers model their vocal lines on older European melodies, in the process distorting the English text; the result allows the singers to pretend they are singing in Italian, which feels more “vocal” to them, but fails to sound much like American English. The more a composer tries to honor speech rhythm in notation, the greater his or her reputation for writing insanely difficult rhythms. This charge has been leveled against composers at least since Benjamin Britten, as seen in the accounts of the premiere of Peter Grimes. The more colloquial the language, the harder it is to flatten its musical setting into a series of eighth notes. The rock drummer turned opera composer Stewart Copeland gives an amusing demonstration of this problem with his robotic straight eighth-note reading of the line “I love you baby. Let’s get it on.” This is pretty much the effect of the text setting in many of the operas of Glass, John Adams, and other minimalists, who straightjacket the language into the motor rhythms of the instrumental parts.4 We can conjecture from Howl and Lives of the Saints that a Lee Hyla opera would have been more expressionist, jagged, and colloquial in its treatment of language than any of these, and that its notated rhythms would look intimidatingly difficult.

Somewhat surprisingly, Lee took a more traditionally songful approach to musical drama in 2003’s At Suma Beach, for which I conducted the Boston premiere in 2006.5 The work is recorded by Mary Nessinger and BMOP under Gil Rose as a companion to Lives of the Saints. In some ways At Suma Beach is indeed a companion piece to Lives : another spiritual monodrama in which the mezzo takes on multiple roles, often delineated by singing in different languages. Drawn from Japanese noh drama, At Suma Beach speaks from a cultural distance that allows Lee to explore a more moderate musical ground than usual, even to create a vocal refrain and some passages of steady pulse—another musical and dramatic color he might have used in his Caravaggio opera.

How might this fiercely individual composer have approached the political aspects of Caravaggio’s life? Lee wasn’t known for political activism, musical or otherwise, but he certainly had a lively artistic response to suffering and injustice, as in his depiction of the torture of St. Lawrence in Lives of the Saints.

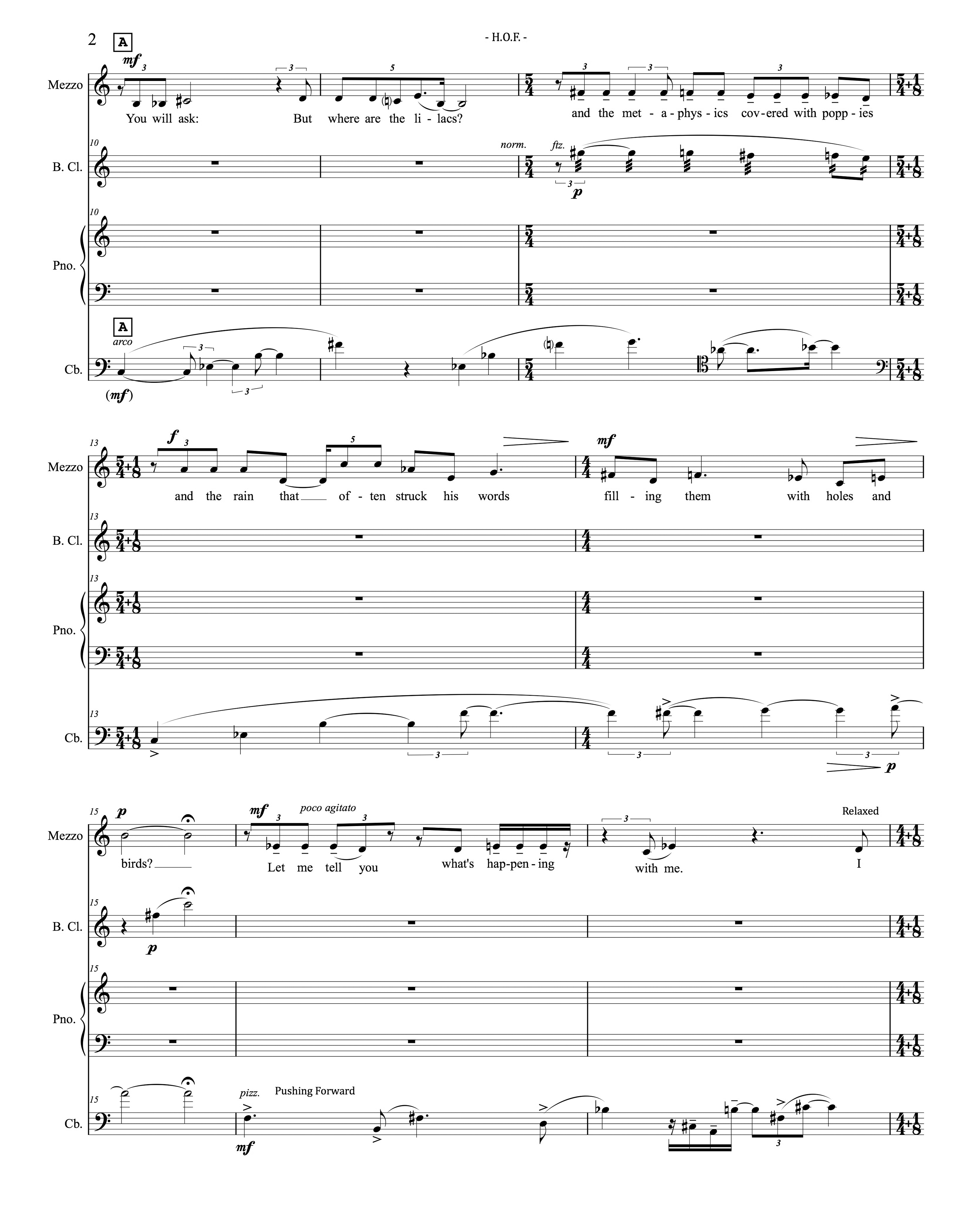

Injustice is also the theme of his 2004–5 Neruda setting House of Flowers, which doubles as a defense of his own extreme aesthetics. The low register that begins the piece recalls the parlando passages of Lives of the Saints. Speaking of his poetry, Neruda says : “You will ask :/ But where are the lilacs?” Surely Lee was asked a similar question many times : “Why can’t you write pretty music with beautiful melodies?” Neruda’s answer is political : “Traitors, generals, look at my dead house/look at Spain broken. From every house flaming metal bursts instead of flowers.” The register shift is repeated, compressed, with Neruda’s return to his opening question, again in the lowest vocal register : “You will ask ‘why doesn’t his poetry speak to us of dreams . . .’ ?” And the answer, again in the singer’s highest register, ends the piece : “come and see the blood in the streets.” This Neruda poem is a response to the fascist bombing of Guernica, the same event that inspired Picasso’s painting of that name. The poem and the painting are political statements, as is the Hyla setting. It is also an eloquent defense of the rebarbative qualities of Lee’s powerful music, in which he places himself in both the political and the artistic line of these modernist masters.6 Neruda’s matter-of-fact diction, which begins “let me tell you what’s happening with me” is quite close to Lee’s own voice, simultaneously casual and deadly serious.

Lee was a devoted birdwatcher, so it’s perhaps not surprising that he addressed animal as well as human suffering. His 2001 Wilson’s Ivory-Bill, for baritone, piano, and pre-recorded woodpecker, is a darkly hilarious setting of a prose account by Scottish-American naturalist Alexander Wilson (1766–1813), who shot and captured an ivory-billed woodpecker, now probably extinct. The baritone alternates between singing and precisely notated speech. The surprising musical connections among the recorded birdcalls, the piano, and the voice create an almost vaudevillian musicalization of Wilson’s horrifying story.

The narrator’s assumption of his dominion over nature reads today as a demented excerpt from an American account like Lewis and Clark, or perhaps a dark folk tale by Ambrose Bierce or Mark Twain. Lee’s brilliant setting offers Wilson as an unreliable narrator, an ecological Humbert Humbert. This re-purposing of historical prose is matched by his musical use of the recorded birdcall. I remember that Lee joked he was “writing a piece for an extinct woodpecker. You’d be amazed how hard it is to find an extinct woodpecker who can count.” In fact, Lee did transcribe the rhythms of the birdcalls as precisely as he notated the rhythms in the piano. His wry comment gives a glimpse of the very American, dark humor of this intensely professional craftsman. We have another glimpse of Lee’s dark humor in a surviving note for the Caravaggio opera, which brings to my ear the spoken voice of our late friend : “I’m back, it’s me, Michelangelo. No not that one—according to the New York Times I just killed him. I’m Michelangelo Merisi de Caravaggio.” It’s good to hear that voice again. Actually, his voice has been with us all along.

An excerpt from Hyla’s setting of Pablo Neruda’s poem House of Flowers. The Neruda’s answer to the question, “But where are the lilacs ?”, is “an eloquent defense of the rebarbative qualities of Lee’s powerful music . . .”

An excerpt from Wilson’s Ivory-Bill, showing the precisely transcribed and notated rhythms of the titular extinct woodpecker.

Score excerpts from Lives of the Saints, House of Flowers, and Wilson’s Ivory-Bill provided with kind consideration by Carl Fischer Music.

1 Renée did premiere my Sunday Songs in recital at Alice Tully Hall in New York and Wigmore Hall in London, both in 2000.

2 A more recent, non-linear religious modernist opera is St. Francis by Messiaen, which reportedly inspired the meditative philosophical operas of Saariaho, but I’m not sure Lee knew any of these pieces. I imagine his would be a bloodier, more violent sort of opera, and possessing an irreverent American sense of humor notably lacking in the works of these impressive, but sober, Europeans.

3 The move from recorded speech to live spoken voice, usually miked, creates more dramatic opportunities but presents trickier musical challenges for composers, which have been variously addressed by the hypnotic mumbling of Robert Ashley’s “operas,” Laurie Anderson’s charming musicalized storytelling, the elegant comedy of Harold Meltzer’s Sindbad, and Kate Soper’s hyperactive combination of speech and extreme vocalism. In many of these cases the composers are also the performers, at least at the premieres, which mitigates the notational challenge of matching speech rhythms and musical ones.

4 The tradition of connecting the natural musicality of American English to operatic singing does have a strong lineage in folk and popular song, including musical theater, and in an operatic tradition, including Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors, and Thomson’s The Mother of Us All. This is a rich and rewarding approach, but it’s a demanding discipline, taken up by few modern composers of opera. I’m often shocked to find that composers are writing opera but aren’t well acquainted with the greatest works of this tradition, especially the shows of Stephen Sondheim.

5 Pamela Dellal sang for that performance, with Dinosaur Annex.

6 House of Flowers was premiered by Mary Nessinger with Sequitur and performed at Tanglewood in 2011 by mezzo-soprano Jacquelyn Matava.