Leave it to a native New Yorker to drop me—a transplant from the Midwest—into a spontaneous scene of global political assembly. In September 2019, I found myself standing at the end of 47th Street in Manhattan, staring at a long row of NYPD guarding the United Nations for the 2019 Assembly. On the way there, I passed protests against—among other things—U.S. interventionist policies in Venezuela. I had walked through a long line of tinted-window, black, SUVs, and that’s where I found Sean.

The day before he had sent me a text message: “free ticket. tomorrow. 2:30.” I accepted the offer and found myself significantly underdressed at a gagaku concert performed by Reigakusha at the Japan Society. Witnessing this group was something I’ll never forget. Every aspect—each movement, each note—was thoroughly intentional.

The pristine, willful sounds of Reigakusha existing amongst the raucous geo-political protests outside are a perfect metaphor for Sean Meehan’s music. He creates works of long, single-minded stillness amidst the constant barrage of the city. His peripheral awareness, empathy, and focus on the execution of acoustically generated sine-like snare drum drones has been deeply inspiring for me. Encased in the subtlety of common objects, his sounds open up into a microcosm of interactions somehow manifested from skin, wood, and metal.

The following interview took place in three online sessions between May 4 and 22. I was in Illinois, and Sean was in upstate New York at the time.

JM How has New York City inspired your life and work?

SM My critical years of acquisition were 1984–90, taking advantage of what the city was like—just getting my mind blown. There was so much good music. High school is when you are really into music—when you’re super porous and everything is weird and painful. The first were Black Uhuru, the Skatalites, and Bad Brains. I saw Bad Brains in ’84 or ’85 and that was like HOLY FUCK. I had no idea! I saw the Art Ensemble of Chicago around then; I saw Sun Ra a lot. You know my Sun Ra closet story? Have I told you?

JM (laughter) NO!

SM This was shortly after high school. Every time The Arkestra played I would go. One time I saw them at The Bottom Line—around Washington Square Park, which is now NYU housing. The Arkestra played two sets that night and they cleared the house between sets. I wanted to stay but didn’t have any money. So, I was gonna hide. The rookie move is to hide in the bathroom which you know they’re gonna check. So, I hid in a janitor’s closet in the backstage area. I get in there and it’s pitch black. After a bit I found a switch and turned the lights on. When the lights came on, I realized Sun Ra was sitting there! So I apologized like, “Oh, I’m so sorry Mr. Ra!” and he told me “No, no, no, have a seat.” So, I sat down on this five-gallon bucket of floor stripper or something—I think he was sitting on another—and he just runs it down—monologuing, talking about outer space.

He was talking about white holes a lot. This was pre-internet, so the next day, at my shitty job, I called NASA. I said “Hey, I’d like to talk to someone about white holes,” and they’re like, “please hold” (laughter). Eventually someone comes on the phone and I said, “Hi, I’d like to talk to someone about white holes. Is there such a thing?” And the guy said, “Oh yeah, that’s totally cutting edge.” So, I’m talking to some astrophysicist about white holes. Sun Ra definitely knew what was going on (laughter).

I was seeing a lot of jazz then. I went to the Village Vanguard all the time and sat in this little corner with all the drummer geeks. I remember the Don Pullen/George Adams group with Dannie Richmond, and Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra with Paul Motian; Motian’s small groups I would always go hear. There was a summer where Ed Blackwell was really sick, and there were a ton of benefit concerts for him. I’d see Don Cherry and Naná Vasconcelos play in a church basement, and Carlos Ward; all the Blackwell cohorts. As part of this, my friend Tom Bruno put on a series in the basement of the Pyramid Club that included Sunny Murray, Bobby Zankel, Charles Gayle, and Rashied Ali. When I saw Sunny Murray, I tried my Vanguard routine and sat in a chair on the side of the stage, and he came out, took a look at me and said, “I know what yer doin’! I’m not fuckin’ Roy Haynes. Go sit in front.” I was probably around 20 at this point.

I knew about free jazz from Val Wilmer’s book As Serious As Your Life so I had my own idea of what it was before I heard the music. Then I heard a concert as part of Bruno’s series with Andrew Cyrille and Frank Wright—the room went totally crazy, like evangelical revival level insanity! That was the first time I heard free jazz that sounded like it did in my imagination.

JM So at this point how long had you been playing drums?

SM Since I was real little. It started with pots and pans. We had a neighbor who had a calypso band and he enlisted me. He taught me how to play a drum kit. I did that forever—same set, same songs. It was a total job for him. He was from Trinidad. He had this band made up of his children. I played calypso forever.

JM At any point did you think you wanted to be a jazz drummer?

SM No. But I loved jazz even as a kid, and as someone drawn to the drum set, you really have to deal with jazz, from Baby Dodds to Papa Joe to Tony Williams to Milford Graves. So I listened to everything I could find. I also read all the copies of DownBeat magazine at the library, especially the Blindfold Test, thinking how amazing it would be to have an identifiable sound! But no, I never thought I would be a jazz drummer, I wanted to be a studio musician when I was a kid. I thought as a session player I could play a lot of different kinds of music with a lot of different people. That seemed challenging and interesting to me, so, that was the goal. The fluidity to play different styles, play charts, play to a click track, stuff like that. Like Hal Blaine or Benny Benjamin or JR Robinson.

In the ’80s, when drum machines came out, all the studio drummers thought they’d be put out of business. So, I immediately bought drum machines and started to program. In high school—I was living in Brentwood, Long Island, at this time—being good at programming helped me have friends. There were a lot of rappers around. I went to high school and was friendly with EPMD and Craig Mack (RIP), and Biz Markie who was older, but hung around; he was always in the parking lot.

JM What do you think was the turning point in how you see sound?

SM A big thing for me was finding As Serious As Your Life and [Hermann von] Helmholtz’s On the Sensations of Tone early on in my youth. Being a library rat, I found those two books by hitting the stacks. I think I was drawn in because the titles are so provocative! Helmholtz’s text is on the physics of sound. I didn’t understand any of it and probably still don’t. But, I don’t need to understand it, really. I like its poetry. It’s totally evocative. And seeing all of that amazing music soon after really got me started on a different path.

From reading As Serious As Your Life, I took free jazz to be Black Nationalist music. It was an extension of politics and a way of living, I wanted to find a way of expressing my own politics, forming a music from that.

When I started playing out with my own projects, all the venues that accepted this kind of music were radical spaces. I played in squats, the Anarchist’s Switchboard, ABC No Rio, The Brecht Forum, Bullet Space, or other somewhat transgressive spaces like Pyramid Club when Brian Butterick (Hattie Hathaway) was booking. There was a link between radical spaces, radical culture, and radical politics. That’s a big part of how the New York I knew really shaped me.

I felt free jazz was Black music, so playing it was something I was never quite comfortable with, but I was definitely inspired by it. I was playing with an older group of people who also loved free jazz, but also 20th-century classical music, New York School, folk musics, and they were more aware of European free improv than I was. The music we were playing was informed by all of this, especially the European improv thing. But it was still deeply indebted to free jazz. I had a recurring morning session at a squat and sometimes Frank Lowe or Luther Thomas or Jemeel Moondoc would play.

I also had a regular trio with [saxophonists] Paul Hoskin and John Dierker that was dealing with New York School composers, Cardew, graphic scores, and less idiomatic improvisation. I loved Paul Hoskin’s sound—his multiphonics, in particular. Every year, Paul would do a 90-minute contrabass clarinet solo. He had this way of using multiphonics to build tension and release with timbre. When I played with Mamoru Fujieda he did it in a much more refined way. Like, using timbre as scales. It felt like he was using intervals of timbre. [Fujieda] inspired me to find ways to do it myself. I’m still trying to build on that.

JM Were you thinking about timbre as something to focus on?

SM It just resonated with me as a way to make music, like an important, underdeveloped part of music theory. It felt like what I had been hearing in my head. Sounds I had been hearing but didn’t know how to make. I made attempts before I played with Fujieda, but I didn’t quite know how to do it.

JM What other experiences or people have influenced you?

SM Initially I didn’t know any like-minded musicians, so I just started working on solo music. My first performance was a concert of drum solos with dance by choreographers who answered an ad I put in The Village Voice. I started working regularly with one choreographer named David Anzuelo, who is a great performer, and through him I met the poet Edwin Torres.

Meeting Edwin was really so essential to my development. He introduced me to so much stuff: Dada, The Futurists, Bauhaus, Russian Suprematism and Constructivism, and Andrei Monastyrski and the Moscow Conceptualist movement. I got all that through him. He was part of the Nuyorican scene. So I was also introduced to all these great Puerto Rican poets like Pedro Pietri, Miguel Algarín, Miguel Piñero. Edwin is such an expansive thinker—

boundless, broad. So working with him was important on that level, but also because he introduced me to the first musicians I would work with.

I had two groups of people I played with: one that had more of what I think of as an artist sensibility, like noise and soundscapes, less idiomatic. This group included Ladislav Czernek, Geoff Dugan, Rachel Harrison, and Tamio Shiraishi. And another group was more from the improv world I mentioned before, which included Hoskin, Dierker, Leslie Ross, Fred Lonberg-Holm, Edward Ratliff, and others. Most of these connections can be traced to Edwin somehow. Also, he was very active, so I got to play all the time, which was important. Edwin and I still work together, and I am still inspired by him.

Around this time, I also started hanging around the Merce Cunningham studio, so I was around Cage, David Tudor, Takehisa Kosugi, Michael Pugliese—and that was pretty important. I was super shy. I loved David Tudor—his music and his way of being. I thought of his music as so radical. Watching him set up and play night after night when Cunningham had the New York City runs was amazing. It was inspiring to be in awe. I was very attracted to all these people. Even though I was trying to be as invisible as possible, I just wanted to be there to coil-up mic cables or something. I wanted to watch them work and hear their sounds.

I also have a life-long love of uilleann pipes [the national bagpipe of Ireland; the name partially translates as “pipe of the

elbow”]—especially Séamus Ennis. To me, he’s the perfect musician. My solo playing is so informed by his music. Sometimes I think my solo playing is a cop-out for not learning the uilleann pipes. Ennis

playing slow airs is the most beautiful thing in the world to me.

JM Does this have anything to do with you being the son of an Irish cop?

SM Well, maybe, but let me tell you, there are lots of sons of Irish cops who don’t give a shit about Séamus Ennis. But yes, I was exposed to it pretty young and have always loved the uilleann pipes, and anyone interested in the instrument ends up at Séamus Ennis. To me, he’s up there with Bach and Coltrane. He’s the perfect musician in a lot of ways. He put the same emphasis on timbre as he did on pitch, melody, and rhythm. That’s something I really strive for. He was deeply connected to the past but pushed so many boundaries. Sometimes my hands are in the exact position they would be in if I was playing the uilleann pipes. When I’m playing sustained tones with the dowel, it just seems I’m channeling Séamus Ennis.

JM When did you get into using a dowel on snare drum?

SM It started by trying to recreate this orchestral percussion technique called the lion’s roar, which is played by applying friction to a string drawn through a bass drum skin to make a roar sound. It is in Varèse’s Ameriques and Ionisation. Early on I attempted a kinda naïve arrangement of Ionisation for solo drum set, and that’s when I concocted my version of the lion’s roar. I figured out a way to do that where I had a violin string tied to a suction cup that I could quickly put on and remove from a drum. At this time, I had every kind of stick possible for different percussive effects including chopsticks and dowels. I figured out I could use the dowel to make the same sound without having to put on or take off the extra device. Later on I figured out that it also worked on cymbals.

At a point, I rejected those the advancements of the 20th-century percussion section—which became so expansive, with Varèse, Cage, and the guy that influenced them, Bill Russell—as being somewhat undignified. Maybe that is too strong a word—but maybe not. Like, if someone wrote a piece for orchestra and lawn mowers, they’d give the lawn mowers to the percussion section, ya know? It felt a bit goofy. I wanted to bring it back to something specific, like a violin player plays violin.

So I started paring down, and getting rid of all of the accoutrement. I was creating my own orthodoxy. All the toys and gadgets got cleared out and I just played drums, and that even got pared down over time. A lot of my development has been shaped by rejecting things. I think this is natural to a certain extent, and part of finding one’s self, but this also conveys a certain narcissistic tendency to which I think musicians are especially prone. Freud has a lesser known theory called “the narcissism of small differences” that has been important to me. He argues that we tend to create the most distance between those who are most similar to ourselves, and there’s a narcissism in that. But, all the things I reject I still love; I’m still excited to hear them in the hands of others.

JM I think that idea is very important to the process of finding a voice. It’s far too common for people to not want to reject anything. It’s not as much an artistic pursuit as it is a social one. That was important for me as a free jazz nerd that wanted to sound like Albert Ayler. I realized it wasn’t my place to do that so, from there, I’m asking myself, “What is my sound?” Focusing in on that requires rejecting a lot of things.

SM Also asking yourself, “Why does Ayler sound that way?” “What shaped him and what’s shaping me?” Ayler recognized the uniqueness of his situation. To just sound like him undermines your own self in a lot of ways as opposed to using your own experiences to make music.

But at the same time, we learn by imitation, and rejection is a balancing of early imitation with a desire to contribute something personal. That’s how you learn music, but you have to aspire to transcend it somehow.

JM Other than the people, what else about New York City has informed your work?

SM There was a real connection between radical music and radical spaces. You could occupy a space in a very different way. We had a space in Williamsburg where we cut the locks and put our own lock on. Yet, it didn’t feel transgressive at all. It had no value. So space was up for grabs in this way and you could make your own worlds. There was a space where myself and Edwin Torres would rehearse and one time four sex workers on break watched us play, and critiqued our playing after we finished. They were right about a lot of it.

Geoff Dugan had asked me to be on a compilation based around notions of psychogeography as articulated by the Situationist International. I had never heard of any of that, so, as I learned more, I realized that their ideas really resonated with how I was using space. At that time, I had been intuitively developing ideas about what theorists like Henri Lefebvre call “the social production of space” [from his 1974 book, The Production of Space]. You can use space, inhabit space, and make a life-world from that space.

JM Speaking of the use of space, can you talk about the summer concerts with [saxophonist] Tamio [Shiraishi]?

SM For nearly 20 years, Tamio and I had a summer concert series, always in a different, elusive part of the city. The spaces were never about sound; most were outdoors and none were really conducive to playing music. For me, it wasn’t about giving a good performance but about creating a situation and experiencing the city in a certain way. We were trying to use these spaces to access the limits of perception somehow—both acoustically and psychically. I felt these marginal spaces somehow engendered this greater experience of marginality. These weren’t shining moments of performance for me. But, I think they were important in building a collective between the audience and the performer. It was a shared experience—a common ground for everyone. I didn’t have to ask people to walk around, they just did. They were autonomous situations by design.

The perfect example was a performance we did where the city stored the salt they put on the roads. It was such a liminal space, was so much about exploding binaries. With these spaces, ideally you would never know if you were on public or private property. You would never know if you were transgressing anything. There would be little chance of being caught or being shut down, because these spaces were completely off the mercantile grid. There was no normative eye, these spaces were voids in the city. Foucault has a great essay about spaces like this that he called “heterotopias” [first mention of this term was made in the introduction to his book The Order of Things]. The salt pile was the epitome of a heterotopia, but it sounded horrible! Acoustically, salt is very absorbent. It was solid white, so it was totally distinct from the city, which was in the background. It was the confluence of all these roadways, but it was totally silent! For example, Harlem River Drive is in sight, but you can’t hear it. I couldn’t really play much but it was an ideal concert.

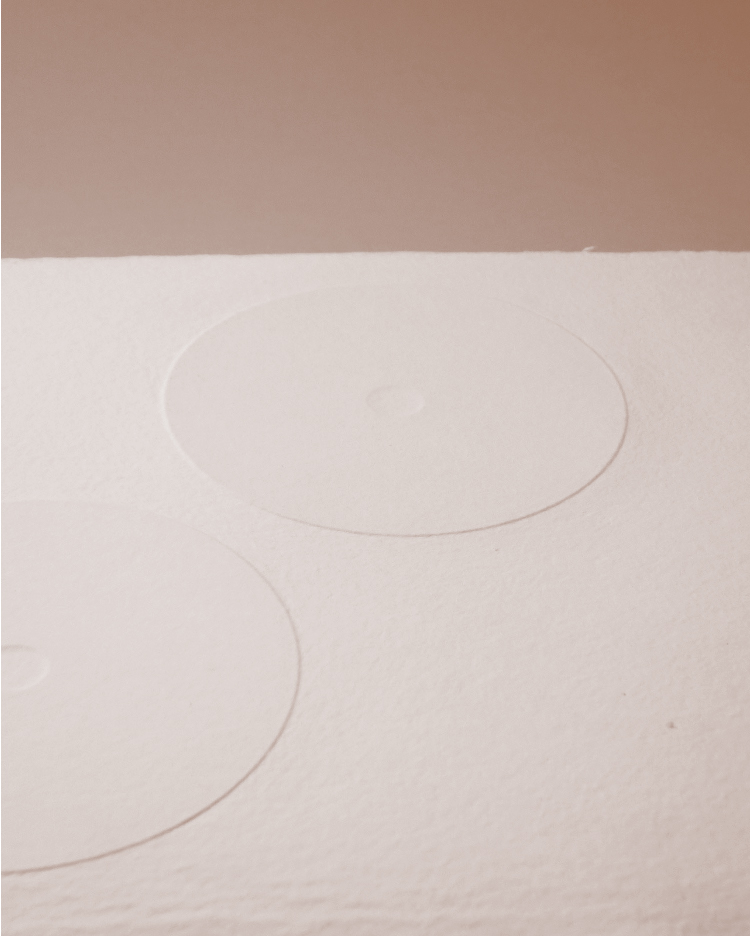

JM I’d like to talk about your album Sectors (for Constant). What was the impetus for the long, mostly silent, pieces and the decision to encase two CDs inside a piece of homemade paper?

SM With the packaging and the music, I wanted to create a relationship between myself and the listener: to engender choices and some kind of participation. With the packaging, there are a lot of options for how to open it (or whether to open it or not). People sent me photos of how they opened it, and I was happy that they shared their choices with me. For some, it was important to find a way to preserve it as a package that they could store on their shelf. One person dissolved the paper with water, took the CDs out, and when they were done, put the CDs back in and resealed the paper with water. Other people used razorblades to take them in and out. In my mind, having to take those actions was mirrored in the music.

On one level, the silences are just rhythm. You need the silence and the note to make the rhythm, and there’s a tension placed on the notes based on the space. I’m allowing room for the listener to do something in that space—ideally, having their own musical ideas, or achieve a collaborative state.

JM Is that a recurring aspect of your work?

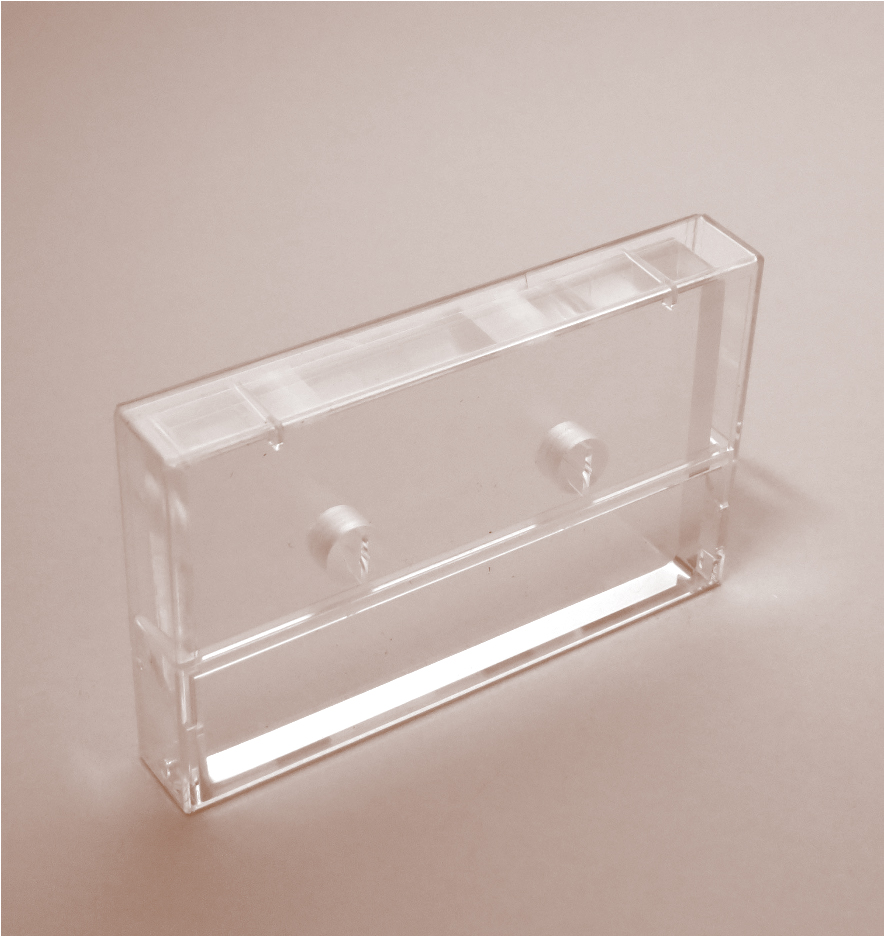

SM Most of the object pieces—for instance, a box set of cassette-like objects called Audio from 2000, and another release called Field Recordings Vol. 3 which are printed pieces—are explicitly that. The object pieces are supposed to suggest music, or act as an invitation to think about sound, as opposed to giving sound. I saw Sectors as somewhere in between a prescriptive composition and a more conceptual piece that invites one to make their own internal, non-cochlear listening experience; a music based on your own imagination and listening experiences as opposed to mine.

These are objects that are meant to be consumed as recordings. They all have musical suggestions on them. But these have always been parallel to my own music making. Sectors was an attempt to bridge these practices and collaborate with the listener.

JM What inspired this as a focus?

SM It’s rooted in my early experiences in the library, listening to the sounds suggested by the Helmholtz book, and maybe some text pieces like Stockhausen’s Aus den sieben Tagen, some of Takehisa Kosugi’s instructional pieces. But there are also some connections to conceptual art, like Lawrence Weiner’s text pieces, for example.

JM I noticed the Audio box set is dedicated to King Tubby.

SM Yeah. When I use that piece that’s kind of where it goes for me, it’s drawn on the psychedelics that Tubby induces in me. If there’s a musical parallel, it’s the space he makes in my mind. I’m trying to capture some of that. I think Tubby’s music is a real dialectic listening experience, where what happens in your mind isn’t equal to what’s coming into your ear.

I was drawn to Helmholtz for the same reason. The main part of my Helmholtz piece [Meehan Reads Helmholtz, see below] is his description of a ballroom. He’s sitting in this ballroom, bored out of his mind at some event, and he’s seeing soundwaves emanate from everything. He’s thinking “a male voice has waves this long, a female voice has waves this long, an orchestra creates waves this long, and these waves all combine.” Like, it’s this totally internal psychedelic experience! That’s totally what these pieces are drawn from. In my mind, King Tubby does the same thing. There’s so much going on that isn’t coming out of the speakers.

JM That really comes through in Meehan Reads Helmholtz.

SM That was intended as an homage to 15-year-old me sitting in a library tripping out. I was trying to replicate that for others, which you can’t really do. But the passages I used in the piece are the ones that really set my mind on fire. It made me excited about sound. Reading that book got me hearing sounds in my mind—my own sounds.

JM Damn. That gives me so much insight, because I think your work is a deeply personal reflection of yourself. When you find work like that, it’s in its purest form. When people are creating work that is 100% themselves and fully fulfilling their own ideas, as opposed to rolling with the hits.

SM Music in general, or the kind of music we make, is such an important tool for self-realization, and understanding the world in some way. Which is a paradox because the music itself is so opaque and marginal, yet, somehow it helps one realize their place in the world. You can’t reconcile this in any rational way but it’s true. So, you don’t really have much of a choice. You have to pursue your own ideas because it leads to amazing realizations—situations, friendships, and so on. It’s paradoxical on every level, but it can really help you understand the world.

JM Is there something about the process that’s beyond a personal practice?

SM I think it taps into something essential, which is then obscured by structures—or superstructures to slightly misuse a Marxist term. It taps into something that we’re alienated from by everyday living—by work and everything else. That’s why it’s a paradox. The whole world is obscured and opaque because we live under this superstructure, but we have this practice that is engaged with something very fundamental, and, there’s gonna be some tension there.

JM Do you find this non-cochlear listening experience—that you talk about with Sectors, Audio, and Field Recordings Vol. 3—carries into performance at all?

SM There are a few ways to answer that. The way I choose to play in a space is very dependent on the room. I can’t just play a piece without considering the space. My performance is dependent on the room and the people in it. Sometimes I show up and play in a room and think, “wow, this is amazing,” and I have this rough sense of what’s possible. Then, the audience—ya know, those bags of water—show up (laughter), it totally changes. I read something about acousticians who actually put bags of water in the seats to simulate an audience when testing acoustics in a space. An audience is a great and beautiful thing, we all want an audience, but audiences have ruined many potentially fine performances (laughter). I can’t tell you how many times I’ve soundchecked in a space, and I can play all these things with the instrument. Then the audience shows up and I’m like “fuuuuuuck.” Nothing is coming back.

I mostly play with my eyes shut, but still, I can totally see the room. Once I’m locked into the room’s acoustics, and the instrument is responding to it, I’m pretty aware when someone walks out, I think. Even if I don’t hear them or I’m not disturbed by them, I know they’ve left, because the instrument responds to that. I wish there was some way I could share how it feels in my body when the instrument is totally happy, and the sound is coming back to it—like animals that echolocate—and the feeling is running through my fingers. Because it’s a really amazing feeling.

You ever see those laser levels that carpenters use? You put the tool in a room, and it measures everything and sends all the data back? That’s what it feels like. The instrument is shooting out all this data and the room alters it before it comes back. It makes a full picture of the room. So, on a very basic level, site specificity totally matters. What the music is going to be is dictated by the room and the people in it—humidity, all these factors.

I also think that the way I perform some of the pieces—especially those using silence—involve negotiation with the audience. It’s about feeling them out and getting permission from them. The cowbell piece I’ve been doing recently—which is quite sparse—feels that way. It’s like establishing some kind of constant negotiation of permission in terms of how far we can go and what we can accomplish together.

JM Something I’ve thought about after my own solo performances—after getting audience feedback—is that these silences can actually make people feel anxious and trapped. It seems like this is something you’ve considered pretty deeply.

SM Yeah, definitely. I think the success of some of the more challenging music—be it durational, or the use of long silences is really about the performer approaching it with empathy for their audience. I have played some very demanding music for audiences that were seriously uninitiated in that world and it went really well. But I think there has to be some kind of trust, for want of a better word. That’s why I try to feel the room out. I don’t want to lose an audience, but I also don’t want to pander. So, you have to strike a balance. Some people have a piece, and there’s an 18-minute silence, they have a stopwatch running, and nothing is gonna happen for those 18 minutes no matter what. That’s a valid approach, but I think it’s more negotiated for me. One thing I did start doing a while ago after a concert . . . if I’m gonna play anything remotely challenging for an audience, especially something that involves silence or duration, when I start I always tell the audience how long it’s gonna be, just so there’s a shift of power because I don’t want to hold people hostage.

I did a performance at a museum in Houston with Sachiko M, and beforehand we decided we’d play for 70 minutes. After an hour, for the audience, I am sure it felt like the social contract was out the door. At 61 minutes, a few people left. So, after 61 minutes it could be six hours! You never know. The power dynamic has totally shifted. So, we’re on the home stretch, and right around 68 minutes everyone left but a few people! (laughter) So, now I don’t want to hold anyone hostage. So it’s like, “I’m gonna play for 40 minutes, if you’re not down, you can bounce, and that’s fine with me.”

A big realization for me was learning I can start again in a given performance. I think it came from watching Indian classical music, where they’d tune up for ten to fifteen minutes, and sometimes the tabla player in the middle of a piece would re-tune. That was important for me to realize that if something isn’t working, I can just stop and start again. Sometimes I’ll spend the first ten minutes of a solo concert just seeing what’s possible, and then building a piece out of what I have learned. The room has settled, the bodies are here, the acoustics are established, what was possible in soundcheck is not possible now. So I will spend time just seeing how the instrument is responding in that moment, and build a piece from that knowledge. That realization was key for me giving better concerts, especially solo.

JM The way you talk about the space being so important to a successful performance reminds me of how Ellen [Fullman] works. When you two would play shows together, did you find that sense was even more heightened?

SM I don’t know if it was heightened but I definitely found someone who really knew what I was talking about regarding the challenges of the spaces we play. Most people have a general sense, but for us, some things just weren’t possible. So, it’s not really “the room sounds good, the room is fun to play in” but “all the things I’d love to do aren’t possible.” You have to quickly assess what the instrument can do in a room and build a piece around that.

I pretty much shut down in the summer because when it gets too humid, I can’t play. I played a show in San Antonio with the vocalist Liz Tonne. The room was humid, and it wasn’t a good room for the instrument, so I knew it was gonna be tough. I didn’t make a sound the whole performance. Some people take it as hostile if, in their minds, you aren’t participating adequately. I hope she didn’t take it personally because I just could not play.

JM Do you like that challenge? The chance that you won’t be able to play at all?

SM I like the challenge of vulnerability—knowing I can’t present my preconceived ideas necessarily. I have to respond to the moment, and I play an instrument that’s very temperamental. I like the focus that comes with it. I like the potential for it to go really awry. I like constructing a piece in the moment based on what’s possible. I like that chance of falling flat. That being said, I hate playing shitty shows.