“Consider the poem that begins ‘padre polvo que subes de España.’ […] Let us attempt to pinpoint the relationship that constitutes this poem as a work by César Vallejo (or César Vallejo as the author of this poem). Does it mean that on a certain day this particular sentiment, this incomparable thought passed for a brief moment through the mind and soul of the individual named César Vallejo? Nothing is less certain. Indeed, it is rather likely that this thought and this sentiment became real for him, and their details and nuances became inextricably his own, only after—or while—writing the poem (just as they become such for us only in the moment when we read the poem).”

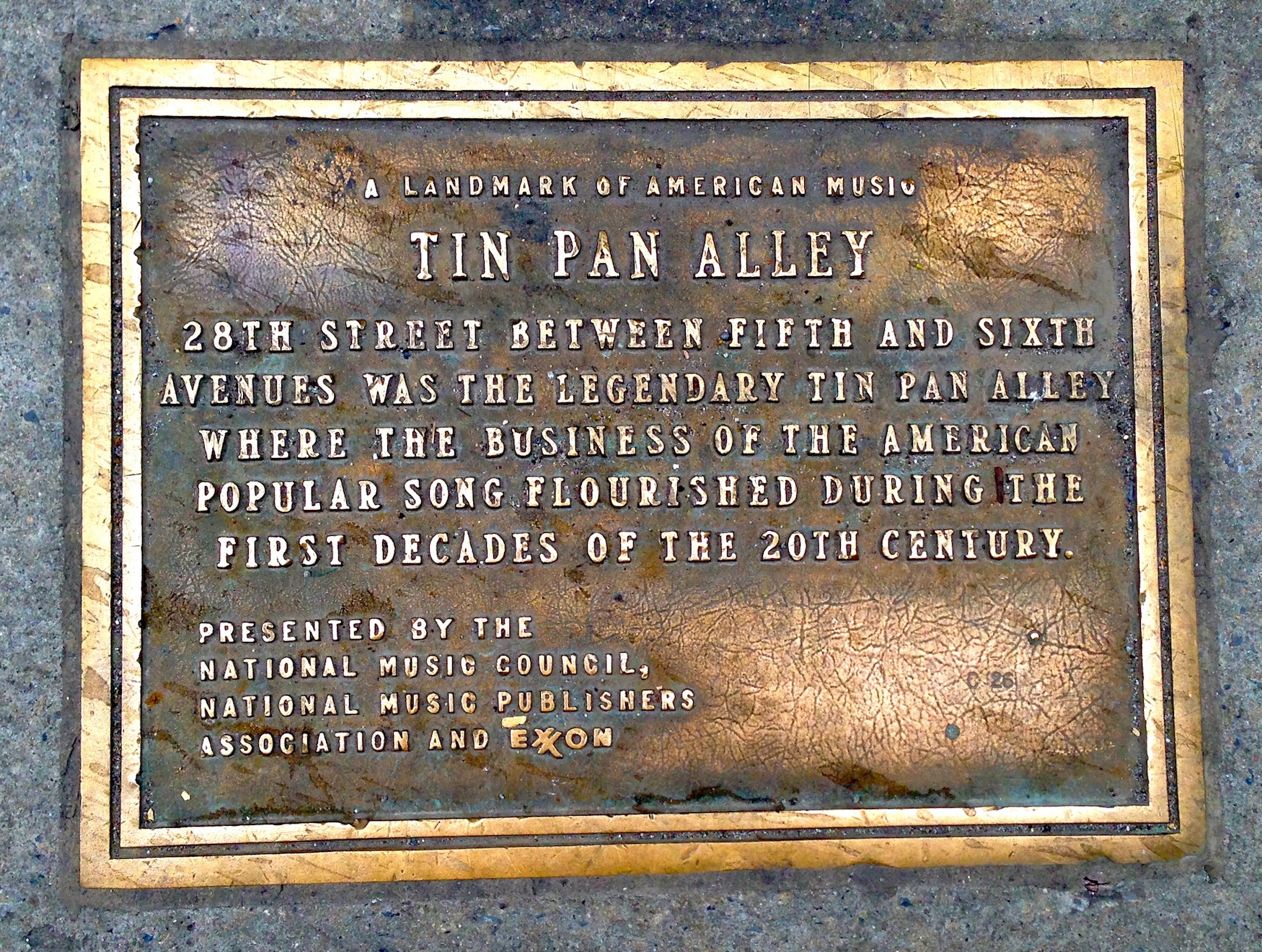

Consider this passage by Giorgio Agamben about authorship, in this case referring to the authorship of a poem by 20th-century Peruvian poet César Vallejo. It has been stuck in my mind since beginning the unusually protracted and pained preparation for this 18th issue of Sound American, which explores the big band.

My personal relationship to big-band music tends to spawn multiple and conflicting metaphors, depending on the memory I’m accessing. As a person who has no interest or business playing in a large ensemble of this type any longer, but whose roots remain firmly within its tradition, the ”big-band sound” conjures images of regimental drills, Quaker meetings, violent mobs, house parties, colorful images—but not always positive. Ultimately, I admit that I am confused about my relationship with this music and have, from time to time, sought out ways to recapture my early obsession with its history and tradition.

One way in which I thought I could regain my early attraction to the wall of sound, the driving rhythm section, the sweetness of an eight-bar solo, and the cacophony of a shout chorus would be by intellectualizing the construction of the big band. When all else fails, I can always fascinate myself with the idea of power structures and hierarchies, concepts that are, almost comically, close to the surface in the history of big-band music, as manifested by the charismatic leadership of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, or Sun Ra, the pseudo-totalitarianism found in the legendary Buddy Rich bus tapes or the overt anarchistic structuring of the King Ubu Orchestra. And, while some of that thinking remains demonstrable in this issue, it is clearly an oversimplification of a grand and complicated art form, and one that doesn’t easily stand up to close examination.

My next attempt was to provide a rudimentary cartography of styles and historical periods. It quickly became brutally clear, however, that the research instigated during my early period of deep love of the form was only going to provide enough knowledge for me to do great damage to the art form. More importantly, as I spoke to the participants in this issue, every preconception that my own big-band experience provided me with was dashed in a way that was humbling. My time spent playing fourth trumpet in big bands does not mean I understand the thinking of those that are knee deep in the tradition.

Now is the time to set my personal reasoning aside and return to the Agamben extract at the beginning of this piece. While he concentrates on the idea of the poet, it is not difficult to access the same idea, using the big-band composer. For example, the composition “Black, Brown, and Beige” began as a germ of an idea that occurred in Duke Ellington’s head. It is a piece that can be said to be a work of Ellington’s (as it can also be said that Ellington is its author). This puts the composer in a special position as the progenitor of the creative idea, and the craftsperson of its presentation, in the same way that Vallejo had the idea, “padre polvo que subes de España,” which was crafted by the poet into the final form of the poem that ultimately followed from it.

And so, the person with the idea is its author or the person who presents it to the world. It’s a very simple and obvious idea, but take a moment to think how incredible and rare this experience is and how we have, every single one of us, been affected at one point or another by this act of authorship. Whether it's the composition called “Black, Brown, and Beige,” the poem that begins “padre polvo que subes de España,” or something more mundane like a radio jingle, the creative process that spans from germinal idea to release into the public is an overlooked mystery of life.

And, to that end, any conversation with, or about, a person who has engaged in this act of authorship—whose existence it informs or defines—is time well-spent in terms of what we can learn from it and the amount of respect it pays to the mystical and pragmatic parts of creation. In this issue, maybe more than any other Sound American has ever done, the variety of attitudes, aesthetics, work habits, priorities, and passions of it subjects has never been greater. In reading the articles within, it becomes clear that the path of authorship is not immutable and the hope of mapping creation is a chimera.

This idea is not limited to the big-band composer or poet, of course. It could be said that SA has been involved in presenting those engaged in authorship from the very beginning, regardless of the work they create. So, what makes composing for and running, or to stay with our metaphor, the authorship of big-band music so special? Let’s quickly return to Agamben:

“Does this mean that the place of thought and feeling is in the poem itself, in the signs that make up the text? How could a passion, a thought be contained in a piece of paper? By definition, feelings and thoughts require a subject to experience and think them. In order for them to become present, someone must take up the book and read. This individual will occupy the empty place in the poem left by the author; he will repeat the same inexpressive gesture the author used to testify to this absence in the work.”

Authorship requires readership—the classic subject/object relationship. This is a well-trodden path and I won’t pretend that my ideas, or even my hackneyed explanation of others’ ideas on the subject, will illuminate anything new. However, the passage above provides specific insight about the authorship involved in big-band music.

Agamben’s example involves a relatively simple one-to-one relationship that goes from author to audience. To expand on his example, Vallejo has an idea and engages in the process of authorship. I read the poem that results and interpret it through my own level of knowledge and experience, changing it through this interpretation. In this way, we are taking part in a sort of authorship of this poem together, his objective act of setting down on paper and my subjective act of interpreting what he’s set down. What occurs in musical composition is a version of the same thing. However, the result of that initial “setting down” is mediated by musicians providing their own intermediate interpretation of the objective composition in the act of performance. This mediated interpretation of the original, in turn, is interpreted again by the listener witnessing the performance or hearing a recording. Anyone needing a concrete example of this mediation effect need only listen to the difference between Maurizio Pollini and Glenn Gould playing Schoenberg’s piano music.

However, big-band composers and leaders find themselves in an especially fragile and interesting relationship to this process. With the improvisatory nature of the milieu they work in (jazz) and given the regular size of a big band (anywhere from eight to 20 members), the mediation between the objective composing of a work like “Black, Brown, and Beige” and the audience’s experience of it is overwhelming. What makes the big-band composer unique is their willingness to take advantage of the situation, making the mediation of their musicians’ improvisations and idiosyncrasies into a secondary part of the authorship process. Can anyone imagine “Sing, Sing, Sing” without the strangely square tom-tom syncopation of Gene Krupa? How about “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” without the rawness of Paul Gonsalves’s tenor stomping? The mediation becomes authorship and we, as listeners, take the knowledge of that into our consideration and interpretation of the “inexpressible gesture” of the work. Truly magical! How often does this occur in music and how rarely do we, as listeners, marvel.

And, perhaps this is the treasure I’ve been searching for in big-band music. It’s the way back in, or at least some way of thinking beyond the power of a full brass section in your face or five saxophones in locked-hand voicings playing so adroitly. I don’t know. It’s perhaps the beginning of a question rather than the answer to one, but I do know that any action taken in which a community, even one as small as a big band, takes a hand in collective authorship of something as profound and special as music is something to be celebrated.

* Giorgio Agamben from “The Author As Gesture” from Profanations.