For the greater part of the 20th century, critics and cultural gatekeepers have maintained that the stylistic freedom of improvisation in jazz music casts it as a functioning model for American individuality and values. Many of these cultural critics did not pay very close attention to the structural rules and particular grammar of jazz music, and so barely noticed when those rules, put in place to ensure jazz as an American brand, turned into hard laws. The rules in jazz improvisation were once loose but became ossified during the second half of the last century, a time of broad-scale institutionalization of jazz studies. The academic perpetuation of jazz performance laws cast the genre as a codified, dead formal structure rather than a fluid, living musical movement that contained structure. That particular kind of death would not have happened without critical and officiating voices pigeonholing jazz into the curious position of cultural ambassador.

If jazz music, at its most basic, is an improvised musical conversation on a theme, then the best-known jazz musicians are those who have striven to contribute one or another element to that particular conversation. Jazz musicians speak their personal dialect within a historical precedent. Therefore, each subsequent musician and historian of jazz has to choose in which languages, if any, they desire fluency. Concerned as they are with the development of the music, as though it were not mere abstraction but actual sociological performance, musicians have to determine and explain the choices of these personal languages, even if the obligation to explain is only to themselves.

The most famous jazz musicians, seminal figures like Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Charlie Parker, are those whose personalities were both the most legible and the most ubiquitous to mixed audiences, but their musical languages also endured due to the relatively clear harmonic and structural laws behind their personal expression. Their distinctive personas allowed them to endure as pop culture legends and were also the force that made people desire to understand the aesthetic components of their work to the point of imitation. These stylistic imitators, then, perpetuate the critical esteem for their models.

The cultural forces that ensured the enduring popularity of these particular musical languages were often those that operated against expression and continued innovation of their music. The jazz canon was created, as all canons are, after the fact, and so an element of retrospective choice was present. Whatever time elapsed between the market choice of whoever’s records getting pressed and promoted, and the perception of quality of that music in itself, determined the earliest entrance into the origin story of jazz. The jazz that lasted possessed equal amounts of otherness and legibility. A lean too far in either direction meant a musician became either an alien, or a robot.

The quality of jazz music spearheaded by Armstrong, Davis, Gillespie, and Parker, and its public reception, can be judged by the historical integrity and reception of these jazz languages in their own time. This judgment relies on the parsing of a few structures, most of which have to do with which musicians felt like musical outsiders. Other originating forces can be unearthed by asking from whom these musicians felt alienated, and why.

From jazz’s emergent freely improvised music to the studious innovations of Lennie Tristano to New York’s downtown improvisation scene, the inclusion in the jazz lineage of improvising musicians from different countries and the subsequent alienation of certain improvising musical outlaws tends to form a breeding ground for the growth of a definition-resistant jazz-adjacent music. This is of particular interest because the founding of a dominant jazz culture is somewhat shadowy. The architects of jazz music are not, save for a few obvious cases like Marsalis’s, clearly legible, and their dedication to the form often springs from personal feelings about the identities of its originators. Such architects bring dynasties into existence.

Many leading “traditional” jazz improvisers create their music in an echo chamber of hierarchical group values while attaching important vestigial recordings to their work as a means of appraisal and renown. They are hyper-aware that they are setting their work into a canon. By contrast, alienation—the continued reaffirmation that all innovation counter to the dominant by those who consider themselves strangers—has established or colored the historical and economic situations that maintain this canon.

An examination of the economic realities of the musicians who feel the pressure to function in the twinned representational form of government and jazz musical institutions reveals the effects of this kind of cultural alienation. The pressure to represent America, its governmental form, and the jingoistic demands on mid-century improvised music practices is one of scant true points of unity between contemporary musical subcultures. I find no greater culmination of this dynamic than the creation of the Jazz Ambassadors program.

The U.S. State Department created the Jazz Ambassadors program in 1956, officially establishing a certain type of jazz music as an American brand. The program was the brainchild of black congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., who represented Harlem in the House of Representatives from 1945 to 1971. Powell, a life-long activist, had noticed that the Eisenhower administration’s arts-propaganda tours through the developing Soviet Union had proven relatively ineffective. Competing with Russia’s long history of ballet and opera had set the U.S. at a steep disadvantage, despite the public defections by several of the major players within those touring companies. Powell’s idea to bring international attention to an indigenous American art form was inspired, inclusive, and placed some “official” value on black music outside its already considerable cultural and market prominence.

Powell’s program recruited legendary jazz musicians to promote the character of American democracy and culture to other countries via their work. These musicians would play their ostensibly Real American music in the countries ravaged by the war, representing the American principles of freedom within structure and the importance of one’s own voice through their music. Like most propagandist programs, its success was dependent on how many of those values were embodied in or desired by their audiences.

The jazz musician in the role of ambassador was meant to appeal to those foreign audiences whose view of American racial politics was, with good reason, negative. By the middle of the 1950s, the civil rights movement had become a major international news story. The Soviet Union had made some of its most enduring propaganda as a direct response to the horrifying American treatment of its black population. Simultaneously, jazz had become extremely popular in foreign countries. What better indicator of progress and social advancement could there be than placing leaders of a predominately black art in the fore in representation of America, typically in mixed race bands ? The government apparently hoped that the novelty of America promoting its jazz superstars and their mixed bands in developing countries would distract from the escalation of racial tension in its own.

Another, more thoughtful, appeal of the jazz musician in the role of ambassador could have had to do with the immediacy of the art form. If indeed a real-time moment of improvised music only exists once, records, as documents of that moment, become suspensions in time. Audiences who attended Jazz Ambassador tours were blessed with these sorts of momentary spells, by having a chance to hear and feel American time outside of the records that might have found their way past the borders into the listeners’ countries.

Free improvisers already experimenting with time-perception in music in both European and Afro-centric contexts were in some ways influenced by the modernism of early 20th-century literature, which placed real value in the conscious experience of everyday life and its rhythms. Jazz, by its nature, reflects—in the singularity of the moment inherent in the improvisational art form—that modernist experience, but especially the rhythms of conversation. This trickling down of modernist values of humanity into mid-century American high culture paved the way for hip white audiences to join black jazz fans and artists in conversation with the personal nature of black American music. Modernism fused with documentation through recording to create—if not quite “the” present—“a” present. For foreign audiences, that could be a portal.

It is doubtful that the congressmen involved with the creation of the Jazz Ambassadors were thinking so philosophically about what it meant that improvisers were representing the American government. If they had, they would have seen the most exciting reading of the Jazz Ambassadors program : that America was the first major global power that acknowledged improvisation in the creation of its strategies. All global powers, big and small,

improvise—they make choices within contexts, organize systems of establishment for their laws in their own languages and through that, render their values transparent and comprehensible. By sending Americans improvisers on tours through countries that would need to improvise in the spirit of the earliest jazz—with little to lose and some symbolic victories in the way of political identity to gain—the Jazz Ambassadors program was giving the developing world a new structure on which to model its own creation, while refusing to examine its own structure, or the real formal subversions within its representative music.

The Jazz Ambassadors program coincided with the apex of bebop as a critically popular art music and radical black expression. Though in some ways bebop began as a rebellion against swing and its foundational idea that black musicians could only be economically supported for their music by making background music for dancers, it rapidly established its own, drastically different and radically specific artistic qualities. Mutating the frenetic quickstep of simultaneous group improvisation from jazz’s earliest innovations, bebop set the soloist against an active rhythm section in a complementary opposition, figuring their vocabulary against a shifting background in a celebration of personal language.

Bebop was energy music that valued virtuosity and singularity of voice over the mass unity of big-band arrangements. People led smaller groups, small families of similar facility and with similar languages, notable for their solo playing, not primarily the arrangements by one or a few. If swing and big-band music was the grand 19th-century novel, bebop was Ulysses. This emphasis on the individual coincided with post-war anxieties around conformity, lending a sociological aspect to the difference felt by these musicians.

Bebop’s rise to critical prominence caused some backlash for many of the virtuoso arrangers and bandleaders of the big-band era. Before, bands and scenes served as micro-congresses within a larger cultural industry. One person, or some people and their manager, would pay musicians for their nights’ work. Often the studio heads and the jazz club owners were mobsters, so there would be some dilution of the funds, as well as dangerous, unregulated playing conditions for the musicians. When black musicians in this musical genre came to prominence, their critical reputation would often result in white appropriation of their work, and that appropriated version would make it into film and radio. Being cheated by the scions of the cultural industry became part of

the deal.

A number of governmental and white-worker-owned union policies led to the alienation of jazz musicians in the early 1940s. Fuel rations from World War II made it unworkable for bands to tour the U.S. the way they had, and when they could manage to tour, Jim Crow laws and segregation made it nearly impossible to find hotels and restaurants that would serve them. Low guarantees and mob control by racist Euro-American club owners kept touring jazz bands in the red. Artists who served in the military created proto-bebop in their Army bands but would still have to bear witness to lynchings and anti-black brutality within the military. The broad-scale cultural trauma of being used for military work and public consumption was a historical, received pain transmuted into their wartime present, in which individual techniques for survival had everything to do with reassigning agency and personal meaning to one’s own body.

The musicians who had come up before bebop were just as dedicated, just as proud, and just as embodied for consumption as beboppers were. Their bitterness had less to do with bebop’s musical innovations and more that they felt the critical embrace of these innovations had led to the ultimate cheat. After playing art music in the background of clubs for dancers, this generation of musicians watched as fairly endless second-rate musicians made rip-offs and appropriations of their work. Meanwhile, young beboppers were receiving critical acclaim for recording aggressive, inspired music that required a different level of attention from their audience. Hip white critics and audiences were, all of a sudden, hearing something in the music of bebop that more commercial swing bands had already been embodying and communicating to dancers. When art music became popular, the swing musicians appeared to have felt like the artistry inherent in their music was ignored in favor of the baroque, and most importantly the flashy, and the personal over a group identity or leader mentality.

Not only that, musicians who were legends in the early 1930s were forced to audition for big bands just a few years later, or were told by young fans, “nobody plays that stuff anymore.” Bebop’s innovation, the presentation of a common language built to keep white exploiters from imitation, had alienated some of its predecessors who could not speak it with them, or did not want to speak it at all. The nail in the coffin for these earlier musicians symbolically rests with bop icon Charlie Parker’s repeated claim that bebop has nothing to do with jazz. That was a line of thinking that, some suggest, makes bebop the first modern black American music explicitly against mass cultural exploitation. It was also one of the first moments of jazz’s history where self-awareness, and its rejection of its “self,” was part of its development.

The alienation of these earlier musicians was a casualty of the innovation of bebop itself. The work was made in part to separate its practitioners and admirers and fans—the people who saw value in the grit and dedication and sweat and sex and light that ran through this particular music. It alienated the casual dancers, the people who preferred swing’s character of background music to bebop’s intense presence. Rather than a group of musicians providing the context for dancing, bebop had its own context. Swing rhythm was in bebop’s origin, but it was pitched so fast that the quality of swing was perceptible more as an affect or a lens than the type of dancing that could couple it.

The difference between swing and bebop is not that of father and son, though that dynamic certainly informs readings of the technical through-lines between both subgenres. The difference is between caste and scene. Swing was not created in order to be an American-sounding music, but by and for a caste consisting of black Americans, most of whom were ex-slaves. Their lives were not dependent on being in the caste, but the caste depended on their identity as nonconsensual Americans ; and all demarcators of the caste identity became techniques of self-preservation. Swing musicians made music that functioned like a government, vaguely reactionary to European concert music but largely sounding out unique orchestrational concerns with the instruments relevant to swing dance music.

Think about the meaning of the two dominant group forms of bebop and in swing. In swing music and jazz music prior, occasional superstars would emerge. Some were arrangers like Duke Ellington and Count Basie. Others were in small groups, like Earl Hines and Louis Armstrong. Others were soloists within bands led by popular arrangers, and those soloists were lesser in status but renowned for their specialties—musicians like Cat Anderson, Tricky Sam Nanton, and Bubber Miley. A hierarchy was formed within bands, with someone like Ellington as a sort of governor of a constituency formed by people like Nanton. Ellington provided the space for those musicians to shine, and for many people, that made it difficult to imagine that artist shining as a leader.

In contrast, bebop vocabularies promoted singularity and excellence, and those singularities created micro-groups who could swing and who had loved swing enough to rebel from it. This sort of sound and determination exemplified self-reliance, though mostly in congress with a scene, mirroring in a weird way the transcendentalist movement of the 1830s. In these respects, the technique of the caste created and undergirded the lifeblood of the movements that came from within it.

This sort of economic and philosophical patronage continues today in both uptown and downtown jazz worlds. In the preservationist jazz universe represented by Wynton Marsalis, Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola exists as a reminder of the eventual co-option of jazz’s ebullient sonic and cultural persona, where the biggest brands in jazz and soda coincide to create a meeting group for American commercialism in the form of acceptable products. It would be hard to imagine a more 1950s-American set of words lumped together, especially in service of a style of jazz music that sets to recreate the energy from that specific time. In the downtown scene, composer John Zorn is establishing residencies and spaces for creative jazz musicians and improvisers to perform their works within a context he created. These are good contexts for musicians to have space in a world where jazz-adjacent performance places hardly exist, and where the funding for it is even less. However, the mere existence of these organizational forces alienates the class of musicians without access to their leaders, who then have to develop their own scenes, with their own places to play, and subsequently their own hierarchies.

What bebop as an art form presented to fans and practitioners was not the ability to forget where in the cultural hierarchy its creators lived, but the idea that musicians could create their own system of governance, their own cultural codes and languages, and in those systems, an affirmation of their own values rather than a class-based hierarchical structure that mimetically imitated the government. In the bebop tradition, tunes were played fast with room for soloing, and the solos could skew even faster. These kinds of compositions served as roadmaps for the group, themes were glossed in a palimpsest over the changes of familiar songs, then further commentary bloomed over a repetition of the harmony of the original song. Bebop heads were skeletal, representing the barest, most essential aspects of the tune—only that which the musicians wanted to preserve.

Swing arrangements were the song, arranging received material. If the material was original, it was fleshed out as the song. Arrangements were fleshy and relatively decaying and, when swing became outmoded, its musicians became guardians of that decay, electing to continue the performance of that style while bebop gave way to post-bop and hard-bop, to free-bop and free jazz, to fusion, and onward and past. Bebop was a mutation initiated by musicians alienated by swing’s obvious commercialism. However, as most successors do, it took the place of that which it originally rejected. When bebop and “modern jazz” musicians became Jazz Ambassadors alongside the swing heroes of the past, they were casting themselves into what would become a historical canon, thus setting themselves up as the alienators of future jazz innovators.

When discussions about the politics of jazz and improvised music arise, the representationalist narrative that allowed for the Jazz Ambassadors program to flourish often couples with the identity politics of the musical creators it supported in order to establish that the music itself, despite its neutrality in most cases, must be political. Listeners, or in this case, viewers, maintain this contention despite the conservatism and representationalism that characterizes the most economically supported and culturally pervasive jazz music.

A curious side effect of this representationalist narrative is that jazz’s most radical musicians tend to have experienced a deep economic and cultural alienation in the same ways political dissidents do. This is due in part to the basic similarities in the identities of artists and dissidents within broader nationalistic contexts, and in part to the triumph of market forces as a metric of success made visible in the economic history of jazz’s growth. While many popular jazz recordings contained a version of the music bastardized by white musicians, the perennial cheat had less to do with the perception of jazz’s cultural success than critical approval and resultant record sales. In the hotbed of racial politics in the middle of the 20th century, a black-representative music seemed politically vital and like a deliberate statement, and in some cases, it actually was. That music—the music of Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman, Abbey Lincoln, and Max Roach—was certainly renowned, but not to the level of governmental co-option.

In this moment of public heat, it makes perfect sense that the Jazz Ambassadors program took place in 1956. 1956 was the year after the Montgomery bus boycott and the death of Emmett Till. Just two years prior, after almost an entire century of officiated inequality had passed, the U.S. Government overturned Plessy v. Ferguson to end school segregation. The Soviet propaganda that had inspired Eisenhower’s artistic and cultural ambassadorship programs appealed to humanitarian sentiment by asking how a thinking citizen could support the country that had jailed the Scottsboro boys. The post-war American government, eager to become the model for developing nations, put faith in an art form made by the descendants of people who were made American against their will, whose innovations and artistry were inextricably linked with the horrors endured by the poor, the black, and the revolutionary. In so doing, the jazz musicians who had received governmental approval became exceptions that prove the rule, and their exceptionalism was often set in contrast to the ambiguous jazz “class” of non-famous musicians.

The emphasis on freedom in the 1950s cultural promotion of jazz often consisted of a bare reminder that jazz music is improvised, or at least represented the Western music where improvisation is most likely to occur. This lazy lack of examination of the structural and formal moments at play in jazz, apart from the novelty of extemporaneous creation, is of the same trend that might allow a version of America’s creation myth to emphasize a colonial relationship to Eurocentric language : Founding Americans valued constitutional language to a degree not quite on the level of the Bible but not far from it either, despite the biblical influence on the ruling style and class of the home country from which they had initially escaped.

In contrast, the story of slavery sets a lot of the values at play in the first narrative into stark relief : After a wave of greedy conquistadors discovered the value of unpaid human labor, they brought African people to American shores without their consent via an unthinkably brutal large-scale slave trade, establishing a racial caste associated with African ancestry. This caste endured the violence of their experience in America by creating their own language and culture, an expressive timeline simultaneous to, yet starkly different from, that of their captors, a language that was so strong and engaging that its theft at white hands in the “art” of minstrelsy was the creation of American pop culture.

The latter story emphasizes pain as a major aspect of the construction of language and culture. The former is a story of relatively untroubled influences. This dichotomy has a near-perfect parallel in the twinned stories of jazz by the government and by its aliens.

The government at the time of the Ambassadors program views jazz as a success story of certain individual American entertainers who encountered the most compelling aspects of jazz and combined them with their personal experiences of sorrow and alienation to create a music that performs freedom. These great men within this genre convinced themselves and others that they are innovators, building loosely distinguishable genres which operated under the influence of certain representative heroes, while simultaneously valuing personal language to a high degree.

A history written by jazz’s aliens would establish the multiplicity of voices that forge a personal language. A language personal enough to allow its speakers to tell the truth without too much received aesthetic interference would be legible to an empathetic other.

These aliens established their intimacy with the true violence of their American experience by creating and reifying their culture through language, and by including within their tradition those who speak to their personal experience with the same level of conviction and dedication each language required.

The Jazz Ambassadors program was cultural imperialism, but the Ambassadors themselves remained outwardly conflicted and rebellious against racist American governance and society throughout the process. In a way, that conflict of representation was the most American thing about the whole Jazz Ambassadors project. To love America, to align themselves with the brand “America” while touring foreign lands, is to have an intricate knowledge of one’s alienation from the harsh reality of the brand “America.”

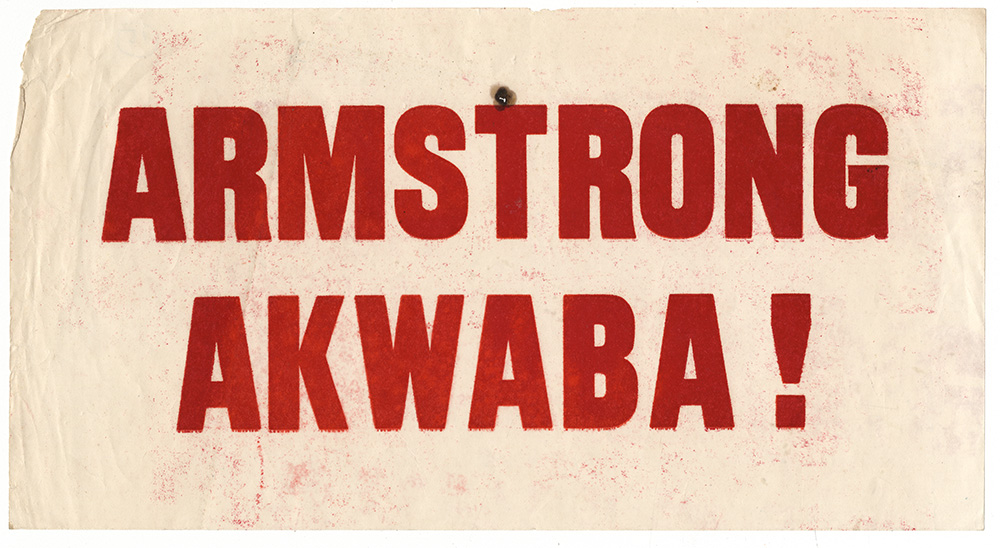

Many of the musicians who participated in the Jazz Ambassadors program felt conflicted about their roles in the program. Dizzy Gillespie, the first Jazz Ambassador, refused his pre-tour briefing with a line as biting and precise as any of his melodies : “I’ve got 300 years of briefing. I know what they’ve done to us, and I’m not going to make any excuses.” In 1957, Louis Armstrong cancelled his State Department tour through the Soviet Union in protest of the Little Rock crisis. He and fellow Jazz Ambassador Dave Brubeck went on to write a musical about their conflicted experiences as Ambassadors, called “The Real Ambassadors.” The script, written mostly by Iola Brubeck, who had accompanied her husband on his Jazz Ambassador’s tour, cast Armstrong as the de-facto ambassador. One musical interlude has Armstrong’s character ask, “Though I represent the government, the government don’t represent some policies I’m for.” Though intended to “bring home the absurdity of institutional political racism in the U.S.,” as Darius

Brubeck would have it, that absurdity was already harrowingly omnipresent in late 1950s American society, and any restatement was just more obviousness.

Examining these three most prominent late-50s jazz ambassadors, Armstrong, Gillespie, and Brubeck, closely, we can see exactly in what esteem the government held the more forward-

thinking elements of jazz music, and exactly what transitions were occurring within the U.S. government, in terms of self-awareness and representation. Young black jazz musicians in the 1940s did not respect Louis Armstrong’s clownish attitude, regarding him as an Uncle Tom. Miles Davis once said :

I always hated the way they [Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie] used to laugh and grin to the audiences. I know why they did it—to make money and because they were entertainers as well as trumpet players. They had families to feed. Plus they both liked acting the clown ; it’s just the way Dizzy and Satch were. I don’t have nothing against them doing it if they want to. But I didn’t like it and didn’t have

to like it.

The audience-facing personas of Armstrong and Gillespie allowed the image-conscious propaganda machine of the State Department to trust that these musician representatives were engaging enough to spread an American message. That, coupled with the conspicuous Eurocentrism of Brubeck’s Milhaud-influenced modern jazz, sent the message to other jazz musicians that they were not fit to be ambassadors if they did not practice respectable politics.

It is clear that Congressman Powell was not planning this tour with the development of the artists’ careers in mind, as most of the musicians chosen to become Ambassadors were already famous. But, Armstrong, Brubeck, and Gillespie were no less innovators for their participation in the program. When Dizzy became the first Jazz Ambassador at Congressman Powell’s request, he was a master and architect of bebop for well over a decade. His tilted horn, puffed cheeks, and unbelievable dexterity were the facets of both his art form and his image. This brand was a curious counterpoint to the self-conscious difficulty bebop had once presented to the listening public. The popularity of his music and singularity of his image provided Congressman Powell and the new program an ideal superstar with whom citizens of developing countries could identify, or at least admire : rebellious in content and politics, untouchable in his aesthetic and technical achievements, loveable in the otherness of his image despite verbalized protestations about the horrifying origins of his otherness. Those protestations added to his appeal, and the Ambassadors program was the attempt at a positive co-opting of that rebelliousness as an American value, despite the horrific ways the American government treated protestors and its non-white, non-cis-male populations.

In this way, Dizzy is almost too perfect a choice to represent America. Not a copy of what America thinks it is, but the mimesis of America, the re-presentation of America to itself. America loves Dizzy for what he can do, and outwardly alienates those identical to him but without his considerable abilities. America loves strong, talented, idiosyncratic men like him. Dizzy was America’s archetype : loveable firebrand, an innovator whose charm is undeniable and tied closely to his idiosyncrasies. The fusion between cultures was an essential character of his music, which was often played by a mixed race, mixed gender band blending bebop with Afro-Cuban,

Caribbean, and Brazilian rhythms in the proverbial melting pot. However, Dizzy was also black in America, and while his rebelliousness and wit saved his ambassadorship from becoming total jingoism, he also, however subversively or inadvertently, bore the burden of having to act in accord with some of the respectability politics of his racial class.

Positioning jazz as the American musical identity cast it as a brand, a sign. Swing, as early as the 1920s, had become a musical signifier of and within American culture, in much the same way blackface minstrelsy nearly a century prior had become the first American popular art form. Jazz music had received international cultural acclaim, finding itself the thematic inspiration and soundtracks for early American films. The critically approved jazz that reached some sort of aesthetic success leading up to and surrounding World War II was one of the first movements in American art music to hit the mainstream whose performances by definition could not be inhabited by people in any other country.

However, for something to become the kind of sign that can be understood by millions of different people, it must remain in some way fixed, however antithetical that is to its origins and practice. Jazz, an unfixed, living expression, has improvisation in its DNA. America chose to have jazz become officially its greatest cultural export when jazz was arguably at its most popular. It was also around the beginning of jazz’s strongest tectonic fractures.

Improvised music like jazz, which relies so much on individual voices, naturally reflects the social time it is performed. In this way, and in their choice to represent this particular American identity, jazz performers dedicated to recreating 1950s aesthetics are forced to embody and confront these racial politics. Many musicians who still perform jazz past the year 2000 avoid critically engaging with these necessary evaluations of race in their reenactments, because for them, they are simply performing “the music” accurately.

When cultural forces affirm that jazz is the American music, they are placing an undue pressure on certain musicians to continue specific subgenres within jazz that might best represent those American values that cultural arbiters fear have gone extinct. The musicians who are willing to play that “correct”—simultaneously extant and extinct—music note the cultural imperialism implicit in calling an art form representative of some kind of nationalism. They respond, not with horror, but with duplication. This process erases the subversion that gives jazz its dark humor and plays it straight, no surprises except the breadth of their own mastery, casting themselves as the music’s victors.

Those unwilling to repeat are cast as active rebels against an American institution. Jazz was the first music whose innovators refused the documentation of the real thing, because they were aware of the likelihood that their work would be co-opted. It was. Most importantly, it was the first music to be considered a national art form that was made exclusively, denotatively, by aliens. Appropriation is a precondition of an alien’s assimilation into dominant culture.

Musicians working within the system, and their large-scale institutional supports such as jazz schools, federal and state grants, and Jazz at Lincoln Center, have tended to exclude other American improvised musical movements like noise and creative music that speak to non-mainstream American values like anti-capitalism,

multiplicity in gender and racial identity, and spiritual unity. They force the music to remain in one semiotic space and time, the time that seems most representatively American to those in control of mass funding.

The representation of American values through jazz music is multi-tiered. It is important to consider how many Jazz Ambassadors were artists and craftsman who had already broken through into cultural legibility and often had some, though rarely very much, financial heft to prove it. Nonetheless, most of these early Jazz Ambassadors were artists who knew real struggle, and transcended it, as much as they could, to become the best of their kind. Most musicians chosen to be Jazz Ambassadors had created aesthetic movements within jazz that gave them international renown as creative heroes, despite how situated in time jazz music is, and despite the considerable allure of an alternate universe that included these more radical sounds and musicians.

If music cannot be divorced from the cultural atmosphere around its inception, why is the jazz-adjacent music that is most capable of speaking to our present so often pushed to the side in favor of jazz historical reenactment ? Perhaps those reenactment musicians love America in a very special way, which is to say they love the America that might grant some respect to the music by its most hated caste, if that America can be convinced that that music is its mirror and its equal. These musicians love the America they see themselves as capable of winning over, and if they are reflections of that America, they need their own hated, enemy sibling to alienate.

In a 2006 evaluation of the Jazz Ambassadors program, the Department of State Post Staff summarized the mission goal of this program as such :

[The Jazz Ambassadors Program] is a vehicle for improving understanding of U.S. society and for opening doors to a variety of publics. Jazz is a metaphor for many of the values we hold dear as Americans, and helps foster the people-to-people connections that promote human understanding.

True to form, bureaucratic advocacy for a cultural art form says nothing about its place in the culture, or the culture. This cold, vague statement renders the work something more product than process, while capitalizing on the connotative value of words like “human” and “people” as shorthand for jazz’s ability to be universally understood. The development of jazz, as a language and a cultural movement, is one that resists understanding. One of the requirements of the advancement of an art form is to prioritize those innovations that resist the cultural ossification of that form. This is the artists’ version of the scientific method. We make a work, occasionally receive affirmation by cultural and/or critical bulwarks, and react to that affirmation by either staying course or changing methods to further arouse those observers willing to stay and listen.